Eddie Hearn: 'I can't say I don't enjoy the limelight'

The boxing promoter Eddie Hearn is telling the world what it wants to hear, live on national television. It is early on a Monday morning. Hearn is in the Hearn family offices, a converted pile outside Brentwood, rural Essex, that was once the Hearn family home, pre-conversion.

“Look,” he says.

He is talking directly to camera, speaking live to a news anchor down the line.

“Everybody knows this is a monstrous fight. It makes perfect sense. How could it not make perfect sense?”

It is 24 hours after Tyson Fury boxed Deontay Wilder in a big-money Las Vegas brawl. Fury won, convincingly. Now the news channels are asking about the heavyweight division’s other premium fighter, Anthony Joshua, who happens to be Hearn’s marquee client. Will Joshua fight Fury now? Can Hearn make it happen?

“Let’s have it right,” Hearn says.

Here he is, a salesman in his element, a heavyweight chatterbox dangling a deal.

“We have an opportunity to make an event,” he says. “Not just the biggest event in British boxing history, but one of the biggest sporting events” – pause – “of all time.”

I can’t say that I don’t enjoy the limelight. It’s a big part of what I do

Hearn is not a man to tone down the hyperbole. Nor does he turn down the opportunity to talk. “I’ll do every interview in the line,” he says, of his commitment to promotion, “and I’ll get to the end and it’s some geezer from… ‘Frank’s Boxing Hour’?” He doesn’t have it in him to turn requests down, he says, even when the requests come from amateur YouTubers. But, you know, all publicity is good publicity. After big fights, news channels clamour for Hearn’s take, not just because he is a grade-A gabber – which he is, a truly exceptional gabber – but because his interviews get traction, particularly when they’re chopped up and shared across social media.

Almost a million people follow Hearn on Twitter, where he delivers lines with the charm and swagger of a star performer. Some 350,000 people follow an Eddie Hearn fan account that reduces his soundbites to memes. Thanks in part to his social media persona – performative, nearly always delighted at something, game for a laugh – but also to the recent resurgence of the heavyweight division as a popular spectacle, Hearn has shot comet-like over the threshold of boxing and into the public consciousness, and established himself as one of the loudest voices in sports. These days, he turns up, almost miraculously, everywhere: on the news, at weigh-ins, on a talkshow, at press conferences, on your partner’s Instagram feed (telling jokes, from quarantine). He can come across as a combination of businessman and comedian – a mostly serious man with a side-hustle in laughs. His company, Matchroom Boxing, promotes more than 90 boxers, including several world champions. But of late it has seemed as though Hearn has become more famous than most of his clients.

Hearn refers to himself as “a travelling salesman” – his schedule, these days, is not carbon efficient – though really he’d like to be remembered for being an outstanding man of business. Some people see him like that. Others think of him as a kind of Essex wide boy, a chancer, ready to pull the wool over your eyes.

The latter take is simplistic. Hearn has sold out events at Wembley and Madison Square Garden. He was the first promoter to make a $1bn streaming deal, with the on-demand service DAZN, and the only boxing promoter to have organised a big-money event in the Middle East (still controversial). He excels at twisting negotiations to benefit the boxers he promotes, particularly their wallets, and subsequently his own, and he is expert at conjuring stories to pitch fights to audiences, especially to those who are only casually interested in boxing. “I love to sell,” he says. “I love to make money. But it’s not just about that. It’s about the achievement of making a breakthrough.”

On days like today, the days after big fights, Hearn is dramatically busy. The machine must whir into action; a narrative must be shaped. (“Narratives are the most important thing in selling a live sporting event!”) When we meet, he has only recently returned from Dubai (family holiday; he took meetings), and he’ll soon fly to Dallas (work). This morning, he has accepted several interview requests – never say no! – though he has rejected one, an exception, from Good Morning Britain.

“They asked me to come on with Fury’s dad,” Hearn says. He is incredulous. “I mean, fucking hell! These people are so naff. It’s like they literally just want to get you having a row.”

I’ve come to ask Hearn about all of this. How he has become a near-permanent fixture in the public eye. How he has transformed from chatty sports promoter into mainstream celebrity, invited on to morning chat shows and cult-followed on Twitter. How he has become more famous than many of his clients, even though they employ him to promote them. I want to ask why he thinks this has all happened. Whether or not it’s been part of some grand plan.

But I can’t, because Eddie’s dad Barry has turned up wanting to know when Eddie will be finished with all the interviews.

“You like the look of my office?” the promoter Barry Hearn says.

Barry’s office is the nicest at Hearn HQ, which is why Eddie decided to film his interviews there.

Eddie shrugs. “We needed to do some work.”

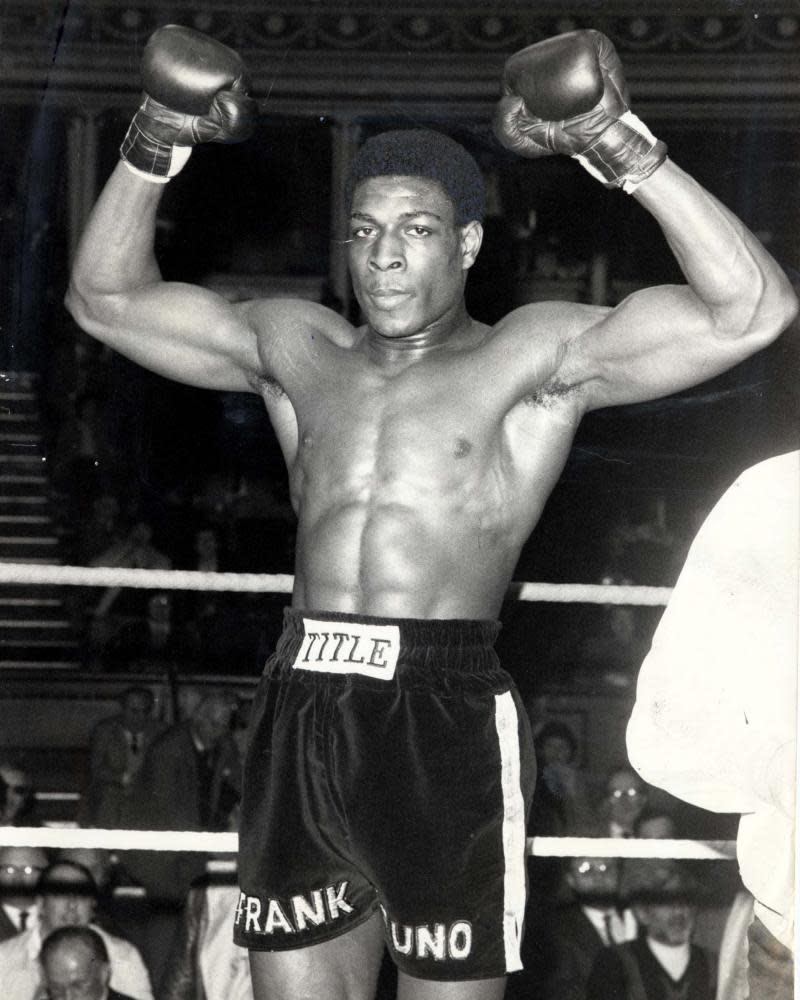

Barry is still technically Eddie’s boss. Matchroom Boxing is a subsidiary of Matchroom Sport, a firm Barry set up in the 1980s and which he still runs. It was Matchroom Sport that gave snooker its big mainstream break, and who later promoted Chris Eubank and Frank Bruno. Eddie still defers to Barry, even though Barry, who is 71, is slowly beginning to cool it with the business stuff, and Eddie, who is 40, is really just getting going.

“I appreciate that I’m working for my son these days,” Barry says.

He looks at the crowd following Eddie around – the camera crews, Eddie’s PR guys, me – then launches into the role of embarrassing dad.

“When he was younger,” Barry says, “he used to tell the birds that he owned this house.”

There is laughter, not from Eddie. Eddie is wincing at the memory, like, “Come on, Dad”. Barry is all smiles. When he eventually scoots off, an aide thanks him for letting them use his office. Barry grins. Then, without missing a beat, he says: “There’ll be an invoice coming, you know.”

When Hearn was growing up, he and his dad were relentlessly competitive, and, without prompting, their relationship colours the span of our conversation. “We sparred at 15,” Eddie says. “We beat the life out of each other in the ring.” Barry came from a Dagenham council estate and made good. Eddie went to a private school and lived in a stately home. “He was petrified that I would become all the things he’d hated growing up,” Hearn says. “The only kid at school with money. The kid at school who’s a bit flash and brash.” Barry still calls Eddie “silver spoon”. “He was so obsessed with that. With the worry of me being, you know, that kid.”

To instil a work ethic, Barry would make Eddie do odd jobs: he shined Barry’s shoes, he cleaned Barry’s car. “He made me his hobby,” Hearn says. “His little project. ‘I’m going to build you in a way where you’re going to be dangerous. You’re going to be good at what you do.’” At one point, Barry had Eddie rifling through the Yellow Pages, so he could cold-call businesses with sponsorship offers. Eddie was still a kid. (The younger Hearn now uses similar tactics with his own kids, two daughters, though he is less exacting.) By 15, Eddie was selling double glazing over the phone. By his early 20s he’d worked at a sports management company, representing golfers, then found his way back to the family business, where he’d belonged all along.

When Hearn was selling windows, cold-calling people in their homes (“The most unbelievable schooling for selling!”), Hearn could take the rejections, of which there were many, one after the other – they made the wins sweeter. What he couldn’t accept was people always reacting to him as though he’d only made it because of his dad.

“I think a lot of it was just a chip on my shoulder of growing up as Barry Hearn’s son,” he says. “When you come from money, people automatically resent you. They think you get opportunities that other people haven’t. True! But you play the hand you’re dealt with.”

At one point, Hearn mentions he feels “manufactured”. I say it sounds like Barry wanted to create another Barry.

“I think secretly what he’s most proud of is that I work as hard as him,” he says. “It’s a responsibility, that I have to continue the legacy.”

Then he adds something odd.

“One thing I’m jealous of is that I never got to make it from nothing. I believe I would have, but I never got the chance. He’s 71 and he still can’t believe what he’s achieved because of where he came from. But I grew up here” – he points around the office – “you know what I mean? So, although I’m grateful, it’s kind of like I didn’t get that opportunity.”

This seems ridiculous to me, to complain about not being given the opportunity to grow up less privileged. I ask him why that’s a problem.

“It’s not a problem,” he says. “It’s just something I would have liked to have achieved. That’s the one criticism I will always get…” That he got a head start. “That’s why I’m so driven to take this to levels beyond anything he could have ever done. How can I be a success if I just maintain the market position? Or don’t show international growth? Or don’t produce the numbers he could never have produced? That’s the competitive instinct between us. It’s like, ‘Come on then, son. Let’s see what you’re made of.’”

I ask if he’s constantly trying to prove himself to his dad.

“Yeah, I think so,” he says. “Subconsciously.”

Do you ever think you will? “I think I have!” he says. “He would never have expected me to achieve what we’ve achieved, because he couldn’t do it. Again, I know I had a head start, but he never got a US TV deal. He never sold out Wembley. He never did a big site deal with the Middle East and got tens of millions out of them.”

Hearn wants to be bigger than his dad. Be greater. “His mentality,” Hearn says, “was always like, he couldn’t believe how well it was going. It was like, ‘Fuck, whatever you do, don’t rock the ship. Don’t fuck it up!’” That’s not Hearn’s approach. “I’m saying, ‘How do we go international? Into different markets?’ That’s the strategy for us. People say, ‘Oh, you’re not interested in UK boxing any more.’ I am! But I’m not going to restrict myself to one market.”

Hearn puts on shows in the US, the UK, central Europe and the Middle East (a hard sell to human rights organisations, but, in his thinking: who is he to tell a boxer he can’t fight somewhere when it means them turning down “the kind of money that secures generational wealth”?) “We’ve built a business and we’ve built reserves and we’ve built wealth to a point where nothing can hurt us,” Hearn says. “The best money to have is ‘fuck-you’ money, which means you can’t hurt. If I lose a fight” – if a fight is cancelled, due to a pandemic, say – “or a broadcast deal, we’re OK, you know? We could walk away tomorrow.”

I ask whether he really would.

He says no.

Then I ask him if it’s because he enjoys the limelight.

“I used to,” he says. “I used to enjoy it. I think it’s become, it sounds a bit arrogant, but it’s become a little bit intrusive. I’m a showman. I can’t say I don’t enjoy the limelight. I guess I do. But I do notice now that…” It’s tough for him to go out with his family without getting bothered, he says. People point at him. People stop him in the street. He prefers not to get the tube now, because inevitably one person will recognise him and before long the whole carriage knows who he is. “It’s just part of what you do,” he says. “You can’t have it both ways. All these celebrities who say, ‘Oh, you know, I’m getting terrible comments on social media.’ Well, you signed up for it! I’ve put myself in front of the camera. I waffle all day. People are going to be opinionated.” He’s stopped using social media as much as he used to for the same reason – people get on his back, for all the wrong reasons, he says. And they are not always gracious. “It’s the Twitter thing.” He means the fan account, the one that reduces him to memes. “It’s made it 10 times worse.”

Worse?

“Worse! Because they don’t even know who I am. I’m just that guy off Twitter. I can’t knock it…”

It’s funny, I say.

“It is, but it used to be a sports fan, right? Now it’s someone’s wife or girlfriend whose husband sent them a clip of me. ‘Oh, that’s that fucking guy.’ So it’s funny in a way. But it’s, like, draining.”

I say that this is part of his new celebrity status.

“I don’t look at it like that,” he says. “I don’t like to call myself a celebrity. I don’t want to be a celebrity. I really don’t. I want to be a businessman.”

It wasn’t part of the plan to become well-known?

“No, never,” he says. “There was a plan to be vocal. To have a voice. But now I’m getting approached to do TV shows with terrestrial broadcasters and it’s, like, hang on a minute, my job is to promote my client, right? I don’t want to be the star. I want to be the mouthpiece to make them a star.” He is musing. “If I can drive a bigger fan base to the sport by being a little bit of a celebrity, that’s fine. But if I’m a fighter, and I’m starting to think, ‘Fucking hell, this guy’s bigger than me…’ That’s never been the aim. That’s never been the plan.”

Relentless is a word me and my dad use a lot: relentless is a word I prefer to greatness

Hearn has a catch-all approach to the press: “Use me and abuse me.” (He also likes to say: “I’m the guy they wheel out.”) But, more and more, the press he does has to be the right kind. “I want to be someone respected for changing the sport,” he says. “Not, ‘Oh, he was the guy on the…’ I’m conscious of that. I don’t want to be… jokey.” He’s considering this, how much to give of himself. “You know, I’ve turned down adverts with major brands!”

Does he worry about failure? He says no, but then he launches into a whole spiel about it. “I worry about not winning,” he says. “Not winning as in not being the best, you know? Not being number one.” Hearn sets targets every year, and every year the targets get higher, “and the fear of failure for me is not achieving those goals. It’s about how big we can be, how slick we can be.”

Hearn is incredibly self-critical. When people tell him he’s done a good job, he won’t believe it. “It’s sad in a way,” he says. “I’m probably not enjoying things the way I should. But it keeps me wanting more.” He’s rarely happy; small mistakes consume him. “The only way you can achieve greatness is to be a perfectionist in everything you do,” he says. “It you’re not striving for the perfect performance, or the perfect product, or whatever it is, how do you really achieve greatness?”

Hearn talks a lot about greatness. I ask him if he wants to be remembered for being great. At first he says no, that he just wants to be remembered. But then he realises that just being remembered probably isn’t enough. “Respect,” he says. “Respect is a good word.” Then he changes his mind again. “Probably the best thing would be, ‘He didn’t stop. He was relentless.’ That’s a word me and my dad use a lot: relentless. Relentless is a word I prefer to greatness. Greatness is an opinion. Relentless doesn’t have to be an opinion. It can be fact.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News