They endured chronic pain and constant blood transfusions. Now a breakthrough drug has given them a new lease of life

Gloria Ademolu would wake every morning in pain. The 26-year-old would need five prescription painkillers a day to cope with the agony caused by sickle cell disease. The engineering student is one of about 15,000 people in England with the genetic, lifelong condition, in which red blood cells are shaped like a crescent (or sickle) rather than a disc.

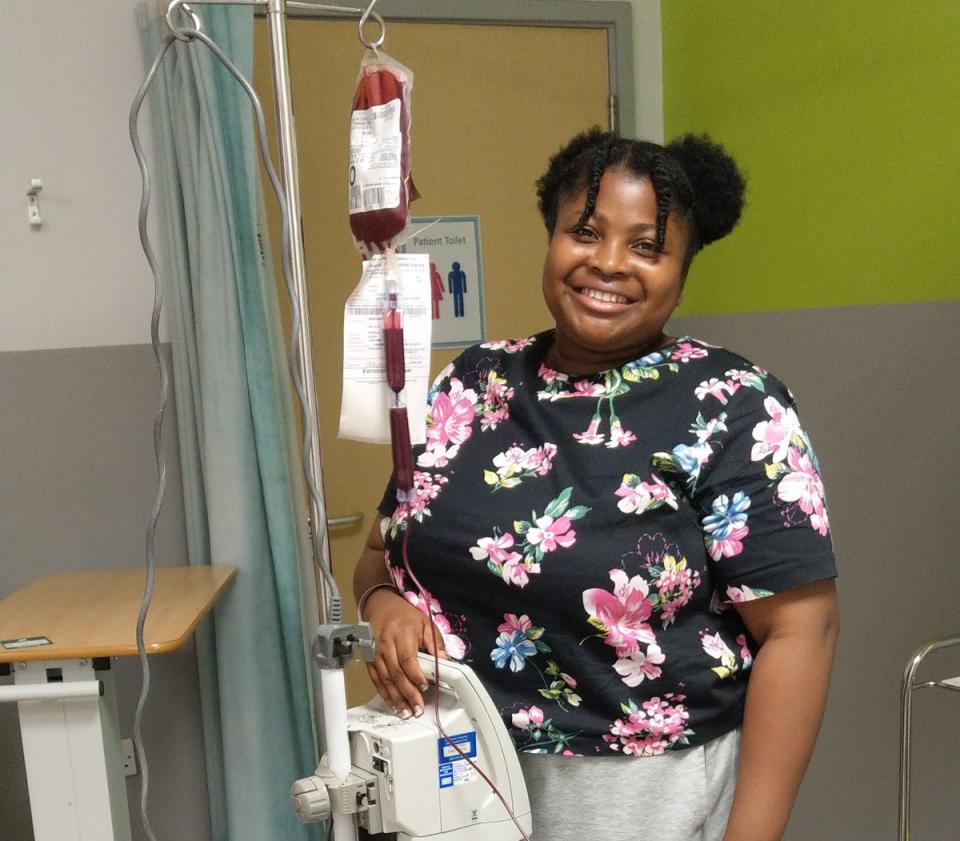

As well as episodes of extreme pain, Gloria, from Manchester, would need to receive eight bags of blood every six weeks during red blood cell exchange procedures that left her exhausted. The disease, which mainly affects people of Black, Asian and ethnic minority heritage, can damage organs and cause intense pain, as well as anaemia because the blood cells cannot carry oxygen effectively around the body, leaving sufferers with tiredness and shortness of breath.

But six months ago, Gloria’s life changed. She began taking Crizanlizumab, a treatment the NHS has given to 180 patients and counting after a deal to make it the first new drug for sickle cell in 20 years. A study suggests it can reduce A&E visits by 40 per cent.

“I hated getting exchanges because it was so painful,” Gloria says. “The last time I was like, ‘Enough, I’m done now.’ I told my doctor, ‘The treatment you said is approved: let’s just start.’ That’s what pushed me, I didn’t want to be in pain.”

There were times when Gloria said treatment options and awareness of sickle cell were so low, that she had to tell doctors in A&E how to treat her and share pain-relieving gas and air with other sickle cell patients.

Now she says she feels “excited” about life because of Crizanlizumab, which binds to a protein in the blood cells to prevent the restriction of blood and oxygen supply that lead to a sickle cell crisis – sharp stinging and throbbing sensations, sometimes suffered multiple times a year.

“I can see the difference in my energy levels and behaviour too,” Gloria told The Independent. “It’s making me want to go out more, go out there, get things done and meet new people.

“Usually I’d stay home and avoid going out because I’m scared of catching an infection but now I feel like I’ve gained a bit of my freedom back.”

Gloria described not just the physical pain, but the emotional and social burden of sickle cell, explaining that her health restricted her learning through days absent from school, missing out on events with friends and in some years spending more time in hospital than at home.

Living with this condition can make it difficult for many patients to continue in their jobs or other everyday activities.

Sanah Shaikh, 32, inquired about Crizanlizumab following the NHS announcement last year, saying at that point she “would do anything to increase her chances of being cured or improving her health”.

The drug is administered every four weeks, and costs £1,000 per vial, though the NHS says it has secured a confidential deal with manufacturers “at a price that is fair for taxpayers”.

Since starting the treatment in April, she feels like she’s experienced fewer crises and the ones she has had could be managed at home with pain medication, rather than requiring hospital treatment.

“Since starting the treatment, I feel a lot safer and braver. I don’t feel as fearful about having a hospital admission if I push myself a little more,” Sanah tells The Independent.

“With this new treatment, I feel like I’ve been given an extra set of wings, to live with more courage and tenacity.”

The 32-year-old has been left with a fear of being hospitalised after experiencing traumatic admissions and being left without medical attention for hours on top of the ordeal of experiencing these excruciating crises.

Sanah says at times NHS staff did not believe she was suffering pain or even had the condition, because it is more common among Black people and she is of Indian heritage.

A parliamentary report last November highlighted evidence of racism and discrimination in the care of sickle cell patients, and last month The Independent revealed an NHS investigation into inequalities faced by people living with sickle cell disease.

“I could be doing everything that I could be doing to look after myself and prevent the crisis but it would still happen,” Sanah says.

“It was so uncontrollable, unpredictable, physically and mentally demanding; it really did start to take a toll on me because I’d be building my life, working and then, all of a sudden, everything would just stop.

“I’d be in hospital tied to machines, drugged up with fentanyl and the sort of other medication to help with nausea from the fentanyl.”

Sanah, who works in marketing, says there is considerable hesitancy around taking the medication – an issue The Independent understands is also causing concern in the health service, which is keen to encourage uptake.

“I went to an event and some of the girls were sceptical because of fertility issues, as they feel that there hasn’t been enough sort of research into how it affects this area,” she said.

Dr Bola Owolabi, who is NHS director for health inequalities, said: “I am so delighted that we are seeing increasing numbers of people come forward and start this new, cutting-edge treatment for sickle cell which is proven to improve people’s quality of life.

“We know that sickle cell disorder can be truly debilitating for patients and so this new drug that reduces pain, reduces sickle cell crises, and reduces the need for blood transfusions, is able to really give hope to people and I would encourage anyone who has questions about it to come forward and talk to a trusted healthcare professional.”

About 8 per cent of Black people carry the sickle cell gene, and, while those with the trait are often carriers rather than those who suffer from the condition, if both parents have the gene there is a one in four chance their child will suffer from sickle cell disease. About 300 babies are born with the condition each year in the UK.

It is hoped Crizanlizumab can give those who do have the condition a better quality of life. As many as 5,000 people could be eligible for the treatment, according to the NHS, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) predicting that around 1,200 will receive it within three years.

“I know that some people have been waiting to see what happens before they take it up,” says Loury Mooruth, 62, who in February became the first patient to start the treatment.

“I want to tell those people to look at me and my experience. I’m alive and feeling so much better. Why wouldn’t you give it a try?”

“I was desperate for a new lease of life which is exactly what it has given me. The boost of energy it gives me is amazing.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News