From ER to The Sopranos: what were the most shocking TV deaths?

Helen Flynn, Spooks

The killer Crock-Pot, from This Is Us, is not the first time a kitchen appliance has been complicit in bumping off a TV character. Remember poor Helen Flynn from Spooks? In 2002, the headlong BBC spy caper was in such a hurry to establish the high-wire stakes of its morally compromised world that Lisa Faulkner’s keen-as-mustard MI5 rookie turned out to be a lot more expendable than her prominent billing suggested. While catfishing an unctuous rightwing moneybags suspected of orchestrating race riots, Helen was captured and horrifically tortured – her hand, then face plunged into a grotty, hissing deep fat fryer. Helen was then briskly executed with a headshot. In episode two! Functioning as both a shocking twist and rather callous statement that No-One Is Safe, it gave the slick drama an instant patina of edginess while generating a record-breaking number of complaints. GV

Will Gardner, The Good Wife

When Will Gardner got fatally caught up in the crossfire of a courthouse shooting, it was an actual TV shocker. Not because neither the context nor the story arc had, up until that point, primed you – in any way – for his potential demise. But because we were four years and 105 episodes into his will-they-won’t-they-oh-please-God-can’t-they-just thing with Alicia Florrick. That that relationship on the brink was never meant to be this eminently feminist show’s backbone, nor Alicia’s raison d’être as a female character, is beside the point. They had unbeatable chemistry throughout – his sad eyes, her husky laugh – that no amount of hesitation, betrayal or extraneous drama seemed able to extinguish. So the fact that he died without her ever really knowing how he felt – when we had known for three whole seasons already – made his death excruciating. A plot twist as gut-wrenching as it was audacious, it cemented Robert and Michelle King’s rep as fearless writers at the top of their game. DBS

Rachel Bradley, Cold Feet

TV deaths rarely shock, because most of them come in ways we can’t imagine. You probably don’t know anyone who was ever killed by an ice dragon, for example. Alternatively, TV deaths are long drawn-out storylines, with a character suffering an illness that conveniently fits into a single-season story arc. It’s a relief when they finally pop off. Cold Feet, of all shows, shocked, in the third episode of its fifth series, broadcast in 2003. Adam (James Nesbitt) had successfully bought a house for Rachel (Helen Baxendale) and their baby son to live in. He phoned her, while she was driving, and passed on the news. The call ended, and she went to change the tape on her car stereo, maybe looking for music to reflect her happiness. She read the tape label, deciding if that was what she wanted to hear. And then a lorry drove into the side of her car. No foreshadowing; no sense of consequences for misdeeds; no inevitability. It was random. It was a death that felt real. A there-but-for-the-grace-of-God death. On a show that often flirted with smugness, it was a moment of hyper clarity. MH

Frank Grimes, The Simpsons

The Simpsons is many things. But shocking isn’t normally one of them. The death of Frank Grimes, though, was a truly transgressive moment. A gambit of daringly bleak nihilism that managed to be simultaneously hilarious and genuinely startling. In spite of a comically hellish childhood, Frank Grimes managed to obtain a degree in nuclear physics. Even so, he lived alone in “a single room above a bowling alley and underneath another bowling alley”. Mr Burns saw a news feature celebrating his story and signed him up. Soon, he was working with Homer, who gorged on Grimes’s special dietetic lunch. He cleaned his ears with Grimes’s personalised pencils. And, perhaps worst of all, he endlessly called him “Grimey”. Before long, Grimes lost his reason and a berserk rampage around the power plant culminated in his death. At Grimes’s funeral, a quip from a bored Homer reduced the other mourners to hysterics. No hugging, no learning. The end. Grimes personified the American dream and that’s what The Simpsons at its best encouraged us to snigger at. So long Grimey. We hardly knew you. PH

Endeavour Morse, Inspector Morse

The 13.66 million viewers who tuned in on 15 November 2000 knew that this 33rd episode of ITV’s landmark cop show was the last. In what turns out to be their final meeting, the detective duo drink beer beside the Cherwell at sunset, and Morse recites the AE Houseman poem that gives The Remorseful Day its characteristically punning title. When Morse, collapses on an Oxford quad, Fauré’s Requiem is, conveniently but poignantly, being sung in the college chapel, and becomes the soundtrack to the closing sequence, until Morse’s beloved Wagner underscores his last breath. Too late to the hospital, Lewis kisses the head of Morse’s corpse in the morgue and says, “Goodbye, sir”, that final formality unbearably right. The scene carried the charge of a double valedictory – from the audience to the series and the actors to each other – and gained a third level of grief after the death of Thaw, aged 60, two years later. ML

Lane Pryce, Mad Men

Lane Pryce’s suicide was gut-wrenchingly tragic. The eminently likeable Jared Harris played Pryce, who first tried to asphyxiate himself in a car whose engine wouldn’t start. But his misery and isolation ultimately won out when he hanged himself. The SCDP financial officer was an unlikely fan-favourite, having entered the Mad Men universe from British firm Putnam, Powell & Lowe. But he quickly became the lens through which many of us observed Don, Peggy, Roger and the gang. He was an intensely empathetic figure, constantly fashioning himself to fit in with the delinquent American drunkards at the firm. But his suicide, which followed his being caught embezzling funds to pay back debts, was a result of his corruptibility. In a way, the writing was on the wall for Lane when Don first bought him a night with a prostitute. But that didn’t make his exit from the show any less horrific and disturbing. JN

Chris Miles, Skins

I remember it as vomit, streaked across the side of his cheek, but actually it was blood that ran down Chris’s face as he lay dying towards the end of the second series. The vomit was on the bed sheets beside him – a gruesome death, even by Skins’ standards, and one that stuck in my mind long after the teen drama began killing off cast members with some regularity. The shock factor was twofold: not only had Chris already been “properly dead” for three minutes just one episode earlier, and survived, but we had watched him waltz through the majority of the show’s drink and drug binges, as well as a spell of homelessness, with relative ease, only for him to snuff it following a subarachnoid haemorrhage – the result of a hereditary condition. LH

Jodi O’Brien, ER

Few programmes managed to deliver dramatic deaths with such surgical efficiency as ER, with more than a few of the hospital saga’s victims being the people meant to save others’ lives rather than lose their own. It would be simple, then, to pick the passing of one of the show’s major players – Lucy, the medical student stabbed by a schizophrenic patient, or the slow demise from a rare brain cancer of Mark Greene, County General’s doc with a heart of gold. But for my money all of them are bested by the events of season one episode Love’s Labor Lost, in which a minor error from Greene snowballs catastrophically and results in the death of expectant mother Jodi O’Brien. In a series that would eventually become overwhelmed by bombast and preposterousness – helicopter crashes, mob hits, the unlikely re-emergence of smallpox – it was the relative unflashiness of Love Labor’s Lost, the sort of story that could happen on any day at any hospital anywhere, that made it feel so horribly, tragically real. GM

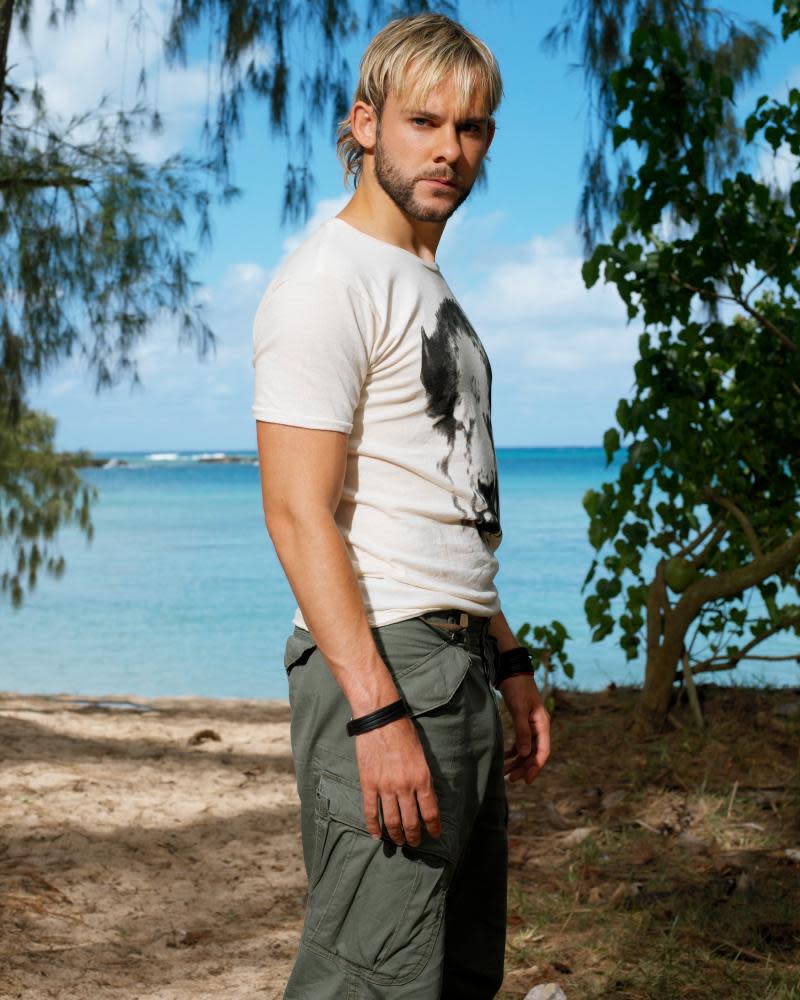

Charlie Pace, Lost

Characters die on TV all the time. But, to date, only one death has affected me to the point that I bought a T-shirt to commemorate it. Charlie from Lost, you impish junkie, I shall carry you on my chest for ever. Charlie’s death was profound for all manner of reasons. He was the first of the big core of Lost characters to bite it, which from a storytelling perspective helped to ramp up the action towards the endgame. But it was also redemptive. Charlie began the show as a self-interested drug addict from the world’s worst band, but he died after a long transformation into a self-sacrificing hero from the world’s worst band. Then, there was the sheer iconography of it; scrawling “Not Penny’s Boat” – the caption on my T-shirt – on the palm of his hand and slamming it against glass to warn his friends of an oncoming attack is a hell of a way to go. So farewell, Charlie from Lost. You may be gone but, so long as You All Everybody remains a solid gold hit, you will never be forgotten. SH

Bodie, The Wire

The Wire was a show that purposefully illustrated the valuelessness of life on the streets of Baltimore by regularly taking it from its characters. By the end of five seasons most of the major characters were either in prison or dead. Omar, Stringer Bell, Wallace, D’Angelo, Cheese, Proposition Joe and Snoop all ended up in the morgue or a vacant row house covered in quicklime. But one death stung more than the others. Yes, D’Angelo’s was cold almost to the point of mundanity and Wallace saw what the drug trade could do to children. However, Bodie – shot dead on a corner for being seen talking to McNulty – lingers the longest. The act, a point-blank shot to the head, was stunningly brutal and showed more than any other, how the street doesn’t provide happy endings. LB

Adriana La Cerva, The Sopranos

Given that The Sopranos was about the mob, it inevitably honed in on violent machismo and men dealing with other men, but in its brilliance, it never sidelined its female characters, instead making them crucial and fully formed in their own right. Adriana was one of the few characters in the show that we could root for and not feel bad about it. Much of the series dealt with shape-shifting notions of complicity, but Adriana, at least, had some approximation of a heart. When she was forced into being an FBI mole – and a deliberately inefficient one, which made it even worse – her cards were marked. There was always a glimmer of hope, though. Hope that despite the beatings and the abuse, Christopher might love her more than he loved his crime family. Hope that she would make the right decision and leave. The fact that we were shown Adriana escaping, alone, before the radio faded away to show her actually sitting in Silvio’s car, was particularly sadistic. Eventually, every bad decision stacked up, as Silvio stalked her from the car to the trees. The two gunshots were off-screen, at least, if you can call that mercy. RN

Ned Stark, Game of Thrones

Given that Game of Thrones has burned characters to death, impaled them through the eye and had them torn apart by their own dogs, it might seem strange to pick a relatively straightforward decapitation as the show’s most outrageous death. But the execution of Stark family patriarch Ned (Sean Bean) in the penultimate episode of the first season was the moment that Game of Thrones signalled to TV viewers that it was something truly different. For most of the season we had watched Ned, the nearest thing the show had to a hero, attempt to navigate the treacherous waters of King’s Landing. Even after he was betrayed it still seemed impossible to viewers conditioned by years of watching TV heroes cheat death at the last minute that this could be his end. When Ned’s head finally rolled to the ground to the horror of his helpless daughters, it was that rare thing in today’s TV age: a genuinely shocking moment that everyone was talking about the next day. SH

Mrs Landingham, The West Wing

Secretary to Martin Sheen’s President Jed Bartlet, she was always addressed by him as Mrs Landingham. So when she is called “Dolores” by him during an exchange in this fateful episode, viewers were on edge as surely as if her desk calendar declared the Ides of March. Mrs Landingham is picking up a new car, which her boss asks her to drive back to the White House so he can check she hasn’t been fleeced. This means (which is also so Sorkin) that it is sort of Bartlet’s fault when a drunk driver jumps a red at 18th and Potomac (explaining a previously obscure episode title) and wipes her out. The off-screen death is reported in a phone call. We see (through frosted glass) Bartlet being told, but don’t hear; even Sorkin couldn’t write that scene. Her loss sets up the series finale, Two Cathedrals, with Bartlett ranting at God in Latin at the funeral, which is probably the greatest single TV episode ever, but that’s a different debate. ML

What did our critics miss out – or get wrong? Have your say in the comments below

Yahoo News

Yahoo News