Family of Veronica Nelson call for big changes to Victoria’s bail laws

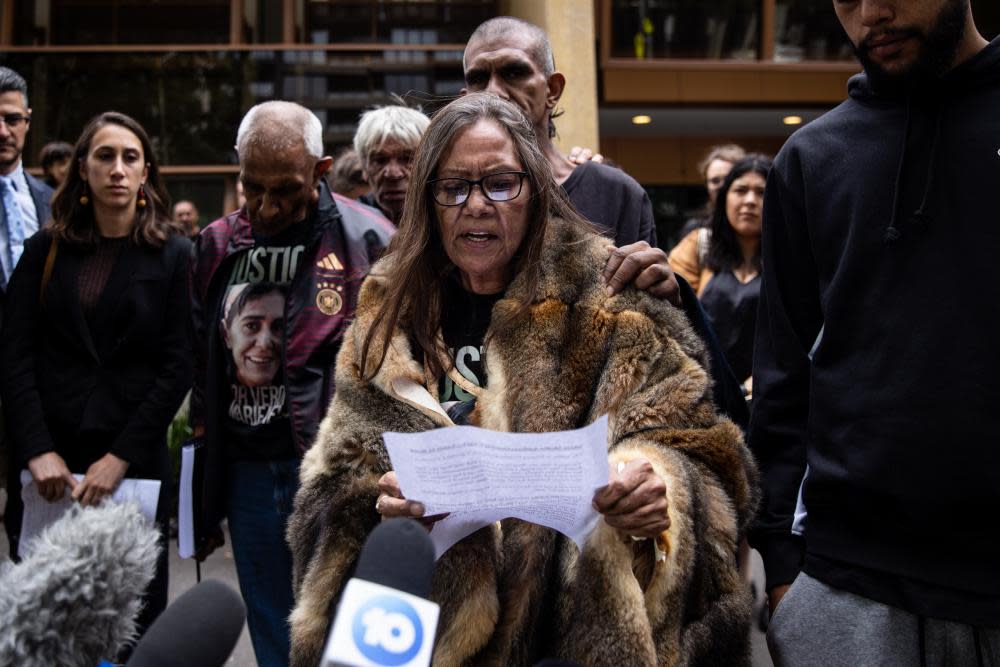

The family of First Nations woman Veronica Nelson, who died while on remand in a Victorian maximum security prison, have outlined what they want the state’s new bail laws to look like and asked that they are named “Poccum’s Law” in her honour.

The Victorian government has committed to reforming the Bail Act after a damning coroner’s report into the proud Gunditjmara, Dja Dja Wurrung, Wiradjuri and Yorta Yorta woman’s death found it was “incompatible” with the state’s charter of human rights and discriminatory towards First Nations people.

However, both the premier and attorney general have ruled out wholesale changes to the law.

Related: Daniel Andrews rebuffs Greens ultimatum, saying he won’t be rushed on bail reform

Nelson’s partner, Uncle Percy Lovett, and mother, Aunty Donna Nelson, are urging the government to go further. They have outlined proposed reforms that are supported by 56 organisations, including the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service, Amnesty International, the Dhadjowa Foundation, the Human Rights Law Centre, and the Law Institute of Victoria.

“They can’t just make small changes and then do nothing else. Everyone should be presumed innocent, they should have a right to get bail,” Lovett said.

“Veronica shouldn’t have been in prison, she should have been at home. If it weren’t for the bail laws, Veronica wouldn’t have been in prison, she would be alive.”

The government is now seeking consultation on a proposal to pare back the controversial reverse-onus and unacceptable risk tests so that they apply only to serious offenders.

Sign up for Guardian Australia’s free morning and afternoon email newsletters for your daily news roundup

The proposal has received in-principle support in cabinet.

But Lovett and Aunty Donna Nelson want the government to remove the presumption against bail for all offences, and explicitly require that a person must not be remanded for an offence that is unlikely to result in a sentence of imprisonment.

They also want all bail-related offences scrapped and bail granted unless the prosecution shows there is a specific and immediate risk to the safety of another person; a serious risk of interfering with a witness; or a demonstrable risk that the person will flee the state.

They have requested that these reforms are referred to as Poccum’s Law – a nickname Veronica Nelson gained after she pronounced possum as “poccum” as a child.

“I want these reforms to be made in honour of my daughter, Veronica, so lawmakers can always be reminded of how cruel and inhumane prison can be to our mob,” Aunty Donna Nelson said.

“Any reform falling short of our demands will not be supported by me, and cannot have my Poccum’s name associated with it.”

Ali Besiroglu, a principal lawyer at law firm Robinson Gill that is also backing Nelson’s and Lovett’s proposed changes, said “nothing short of a drastic and urgent overhaul” to the state’s bail laws would suffice.

“A mere watering down of the current bail legislation will be woefully inadequate and will not address the overrepresentation of First Nations people on remand,” he said.

A new report by the Justice Reform Initiative, released on Wednesday, showed the state’s prison population had soared by almost a third over the last decade.

Related: Daniel Andrews promises Victorian bail law reform after inquest into Veronica Nelson’s death

Called “Jailing is Failing”, the report found the proportion of unsentenced people in Victoria’s prisons had also more than doubled in that time, from 20% of the prisoner population to 42%.

More than half (52%) of unsentenced people in Victorian prisons had been held on remand for more than three months, 32% had been held on remand for more than six months and 17% for longer than a year.

Rob Hulls, the director of the Centre for Innovative Justice at RMIT University and a former Victorian attorney general, is a patron of the Justice Reform Initiative and described the state’s prisons as being akin to “21st century asylums”.

“We are locking people up so they’re out of sight and out of mind, when they really need holistic, wraparound support,” he said.

“It’s not working. We have to think smarter when it comes to our criminal justice system.”

Hulls called for a holistic approach to criminal justice, with early intervention to break the cycle before it becomes entrenched.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News