Firelei Báez review – bring on the furry ciguapas: magnetic visions of diaspora

The first time I saw a Firelei Báez I felt as if I’d found a glowing orb at sea, or made friends with a London parakeet. It was rare and magnetic, an arrestingly beautiful rendering of foliage, waves and hair on an archival backdrop, in this instance schematics and yield tables from a colonial-era sugar refinery. That was in 2019. I haven’t stopped thinking about the painting since. So the fact that the Dominican Republic-born, New York-based artist is finally opening her first solo show in the UK is thrilling.

Titled Sueño de la Madrugada (A Midnight’s Dream) (although madrugada actually translates as dawn in English), the exhibition offers clouds of small paintings offset from the wall, murals that wrap rooms, painted aluminium cutouts and an immersive installation. It is curated by the 2024 fellows of the New Curators programme, a groundbreaking 12-month, salaried course for applicants from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

For the installation, Báez has shrunk the height of the gallery’s main space by suspending layers of blue, tented fabric across it. Cool air from desk fans and ventilation vents makes it flutter. Light from angled yellow-tinted spotlights filters down through thousands of eye-sized slits cut into the folds. Your own eyes start to doubt if the floorboards are flat or straight. People look mottled. There’s the soundtrack of a riverside at night, the chirps of crickets and croaks of frogs melding with the hum of Peckham beyond. Báez’s installations feel like you’ve been invited inside. One of the curator’s mothers didn’t want to leave.

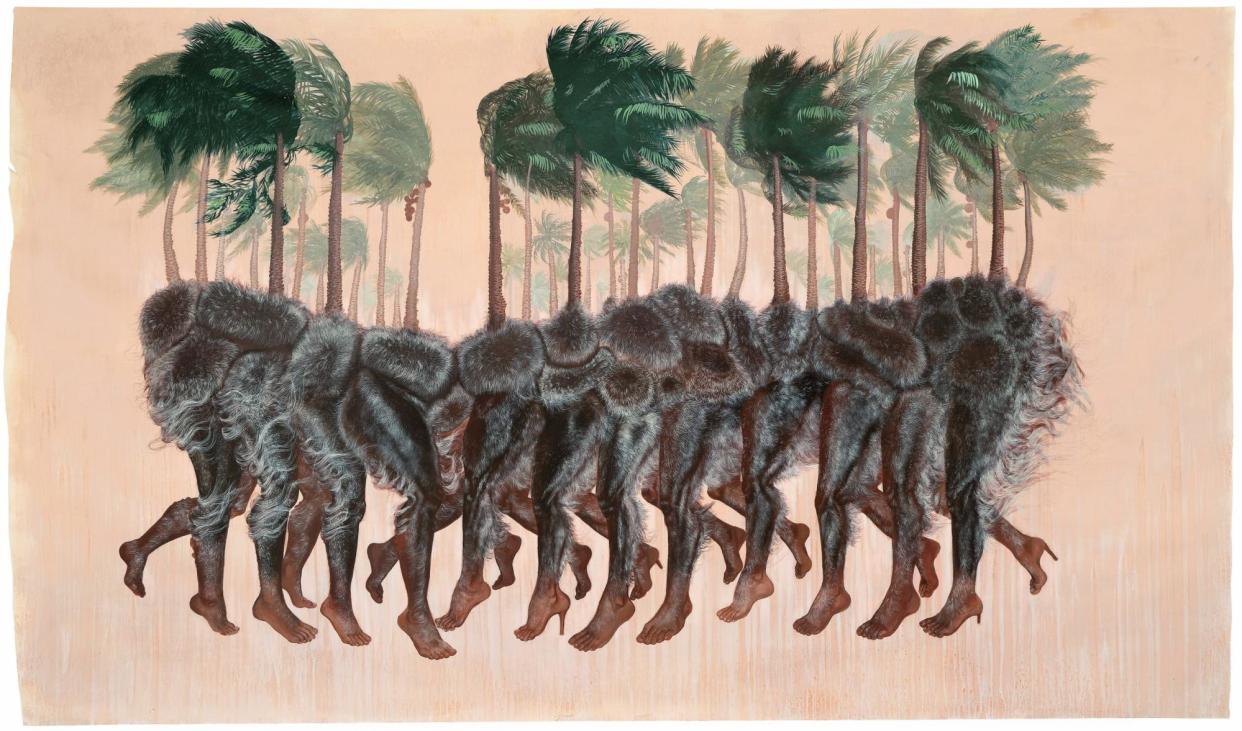

On the floor is the show’s most startling piece, a double Haitian deity in tomato-red neon, as long as a person and laid on a bed of sand: Atabey, the Taíno essence of fertility on one end, and Erzulie, the vodou spirit of love, on the other. The neon-red glow, meanwhile, bounces outwards, on to two large-scale painted cutouts of ciguapas, who are dancing in formation.

This mythical trickster from the island of Hispaniola often has backwards-facing feet, so she cannot be traced, and a hirsute upper body. Here, Báez depicts the ciguapas in silhouette, a flurry of feet at the bottom and canopies of fenestrated foliage and palm fronds at the top. She has poured and layered the paint in underwater hues that accrue in rivulets and sediment. Big armfuls of real foliage, stuck into the fabric with chicken wire, frame the paintings and the doorways while fronds of blue fabric casually stapled on to the canopy hang down in loose tangles and stroke your head as you pass. The whole thing shapeshifts between high finish and decay, danger and comfort, the geological and the cosmic.

Across the road in the gallery’s annex, Báez has made floor-to-ceiling murals. A reclining head of hair lies draped in white, reading Ben Okri’s The Famished Road, her face hidden with flowers. On the opposite wall, an orange ciguapa grows up into a wilting tree. In the adjoining room, tiny paintings and drawings on found book pages (all relating to British colonial history) pursue this heat-and-oppression-resistant idea of one thing becoming another. The hilt of a sword is given folded limber legs. Solidiers in battle see their heads turn to cloud.

In a conversation with the curators and Alvaro Barrington that marked the beginning of the exhibition’s public programme, Báez was asked about her paint-pouring technique. Well, sure, she said, that would lead down an art historical rabbit hole but she thought it might be “juicier” to just get into how it all feels. She remembers being told as a child, that if she didn’t get her hair braided, she’d turn into a guaraguao (a red-tailed hawk), and as an adult later reflecting, but who doesn’t want to be a free-wheeling bird? This show extols the sheer beauty in refusing any such normative or societal constraints. Báez makes whole worlds from fleeting moments. And she brings you into the fold.

Firelei Báez: Sueño de la Madrugada (A Midnight’s Dream) is at the South London Gallery, until 8 September

Yahoo News

Yahoo News