Five things that the west doesn't understand about China's foreign policy

China’s capacity to surprise western politicians was demonstrated recently, when Chinese leader Xi Jinping was unexpectedly absent from the G20 summit. There were a few reasons why this G20 might have been less important for Xi, including the rising influence of the Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) partnership.

But often western reactions to a Chinese decision can come from a lack of understanding of Beijing’s motivations. A deeper knowledge of China would help the west interpret Beijing’s actions more clearly, helpful at a time where many analysts see China as a potential challenger to the US as the dominant world power. With this in mind, here are five things that the west often gets wrong about Chinese foreign policy.

1. It’s not a grand scheme

In the western media, Chinese foreign policy has often been seen as a grand scheme to secure world leadership. Such an image has been popular with western politicians, such as South Dakota governor Kristi Noem, who claimed that China had a “2000-year plan to destroy the US”.

However, Chinese policy is not quite the labyrinthine plot that it has often been presented as. An example of this can be seen in “Wolf Warrior diplomacy”, which has often interpreted as a long-term, calculated strategy of Chinese aggression to western leaders. But another way of looking at Wolf Warrior diplomacy is as an opportunistic response to the bellicose rhetoric of the former US president Donald Trump’s administration as well as a need to cater to nationalism at home. Showing Chinese leaders “talking tough” to their foreign counterparts also plays well with a domestic audience, and can divert attention from a poorly performing economy.

Equally, grander Chinese initiatives, such as the Belt and the Road Initiative (BRI), which provides aid and finance to African and South American countries to create new infrastructure, may also have been created as a response to outside developments, particularly the US pivot towards expanding its influence in Asia, from 2010. Chinese foreign policy has largely been devised in response to recent developments rather than being a long-term scheme for domination.

2. China deals with democracies

Another common fear is that Beijing has encouraged the rise of political authoritarianism in other countries. The Chinese model of economic development has racheted up fears of China attempting to spread its political system beyond its national borders. But, some of the biggest advocates of the China model have been the political elites in developing nations, many of whom have a colonial history, and who appreciate that China offers an alternative to the west in attracting investment.

Read more: As BRICS cooperation accelerates, is it time for the US to develop a BRICS policy?

Overall though, Beijing generally takes a laissez-faire approach towards the internal politics of its partners, with China being willing to deal with democracies and dictatorships, rather than forcing its partners to fall in line with its own political system.

3. China’s role in the world order

One of the most common depictions of China in recent years has been of it as a revisionist power that seeks to overthrow the liberal rules-based world order and international bodies. Such an image was popularised by Graham Allison’s 2017 book Destined for War, which warned of a China seeking to overthrow US domination. It presents the China/US relationship as the latest in the long line of great power relationships that follow the same pattern.

However, while China wishes to amend certain areas of the post-Cold War system, most notably it being centred around the US and liberal values, it does not wish to fully overturn the whole system. For instance, China has played a significant part in established international bodies, such as the United Nations. China was also one of the primary beneficiaries of post-Cold War globalisation, with China’s rapid development being achieved partially through this economic model.

4. China’s historical experience

One of the greatest challenges posed by Chinese foreign policy is that it questions many of the dominant understandings of international relations, which have been grounded in the experiences of the west.

But China draws on a different history, one that includes its own dominant position internationally, but also its defeat and occupation. Beijing references this past when talking of the “Century of Humiliation” (1839-1949), a period when China was dominated and occupied by colonial powers. This powerful image can rally the domestic population as well as building a common cause with developing nations, many of which are former colonies themselves.

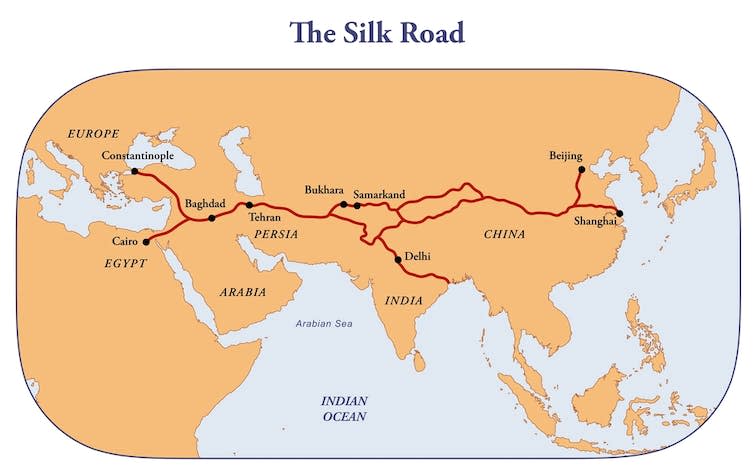

China’s golden ages of the Han, Tang and Song dynasties (202BC-1279) has also influenced Chinese thinking. This was a time of huge cultural and economic influence, with Asia trade centred around the Silk Road. The Silk Road refers to an historical network of highly lucrative trade routes linking a powerful China to the rest of the world, and used to sell its products for centuries. Its ambitions to build a new version of this can be seen in the BRI, which gives China a “new Silk Road”. It is by understanding the logic behind these legacies that one can see Chinese foreign policy more clearly.

5. The appeal of Chinese aid

China’s financial aid and investment projects in developing countries are sometimes portrayed as simply bribing corrupt states or ensnaring them with “debt trap diplomacy”.

While these images have been popular in western media coverage of Chinese foreign policy, they overlook the role of the country receiving aid to choose to accept Chinese finance and how this also appeals as an alternative to western aid packages which traditionally come with many conditions relating to governance.

Chinese military leader and strategist Sun Tzu once emphasised the importance of knowing one’s enemies as well as oneself; these words are especially pertinent in understanding China today.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tom Harper does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News