Five years on, Ukrainians ask if the Maidan revolution was really worth it

“If only I knew where Sergei was running to, I’d have done anything to stop him,” says Tamara Kemskaya, sobbing.

She had called her son at 8am on the morning of his death. She remembers hearing the sound of him panting, and the whistles of what she now understands were bullets. At the time she assumed he was busy, so said she would call back him back. She did not know there had already been about 20 protesters shot dead by that point. She could not imagine that her Sergei would join them less than an hour and a half later.

Five years on, the YouTube clips that flicker from screens in the corner of a Kiev courtroom are all that remains of Sergei Kemsky and his Maidan revolution. Hours and hours of footage show the lead-up to that last battle of 20 February 2014. They show the lines of riot police, the bonfires of tyres, the street clashes, the burning buildings, the petrol bombs, the bodies falling and the desperate operations to save them.

They show Sergei collapsing under sniper fire on Instytutska Street, then frantically trying to drag himself away before receiving a second, fatal round.

Across from the video screens, and three presiding judges, are the five Berkut (riot police) officers who are on trial for their part in the killings. Most of their unit fled to Russia; these men stayed behind. They stand on the other side of a glass cage, largely motionless and emotionless, save for when they chat to their wives and girlfriends through gaps in the cage.

Kemskaya tells The Independent she can barely contain her rage when she looks at the five “well fed, well clothed, happy” men.

“I understand these guys were carrying out an order,” she says. “But for me, they are inhuman. They saw the people in their crosshairs. They saw their faces. But they shot them dead. Why couldn’t they have just aimed at their legs instead?”

The legal process has been an exhausting one for Kemskaya and her family. Originally from Crimea, she now now lives with her husband in a small flat in the Black Sea port city of Mykolaiv – they moved there to be nearer their surviving child, a daughter, and the grandchildren. Mykolaiv is a seven hour drive from Kiev but Kemskaya tries to make it to the courtroom whenever she can. It’s already too late for many of the other parents, she says. A dozen have died from stress-related illness.

For all its failures, the Berkut trial is actually somewhat of a model process in Ukraine. The vast majority of investigations initiated by Ukrainian prosecutors are static, simply gathering dust on shelves. Of the thousand or so cases that have been initiated from a dozen episodes, only 12 have reached trial. An additional 50 cases have been transferred to the court system but have yet to be processed.

Prosecuting lawyer Yevgeniya Zakrevskaya, who cuts a heroic figure in the treacle of Ukrainian justice, says a number of factors have contributed to the delays. On the one hand, Maidan cases are “difficult” with “real-life consequences, often dangerous”, so courts find it easier just to sit on them. On the other hand, she says, corrupt decision-making is “never far away”.

“Those who stand trial are the ones to benefit from delays, and some, no doubt, hope they can put it off indefinitely,” she says.

The lawyer worked on Independence Square from the very first days, collecting video material and testimonies as the revolution moved through its various stages.

Those who stand trial are the ones to benefit from delays, and some, no doubt, hope they can put it off indefinitely

Yevgeniya Zakrevskaya, lawyer

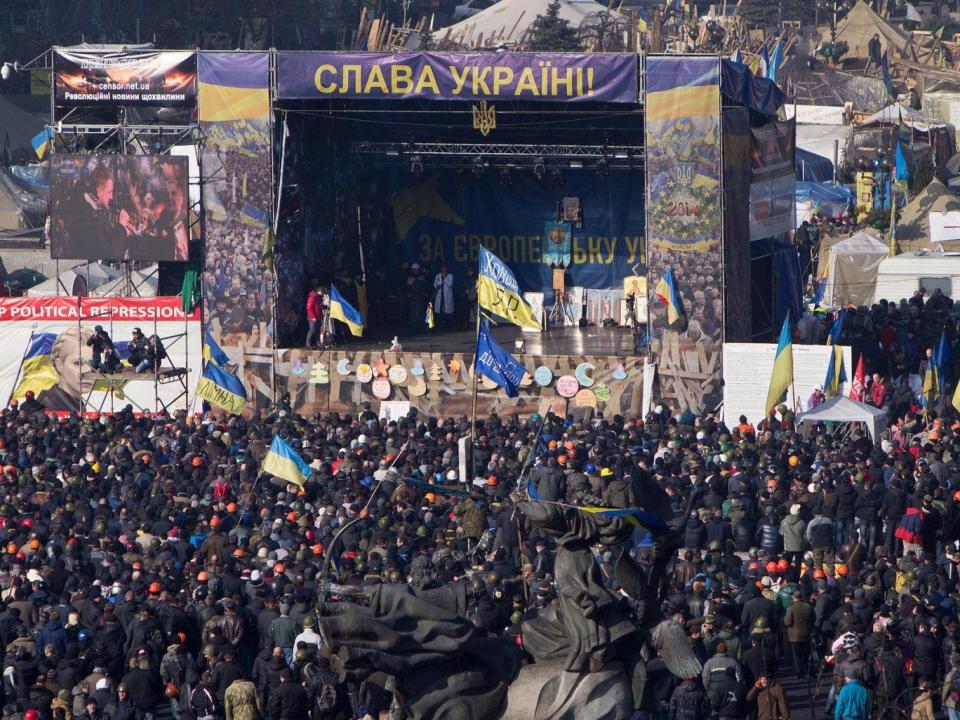

At the start, Madian was a marginal protest attended by activists who had turned out to push Viktor Yanukovych's administration to sign an association agreement with the European Union. The protest became a mass movement when riot police incomprehensibly turned their truncheons on the small camp of mostly students (30 November–1 December). The movement became one of resistance when protesters fought back riot police (16 December). Resistance became radicalised when Yanukovych pushed through “dictatorship” laws (16 January) and when the first Molotov cocktails appeared on the Square (19 January). The protesters became a militarised camp after the first death (25 January). And it ended as a killing field and makeshift cemetery (February 18-21).

Roman Ratushnyy was one of the first to answer journalist Mustafa Nayem’s call to take to the streets back on 21 November 2013. Seventeen at the time, Ratushnyy had to juggle the protest with college, but teachers took a sympathetic view and allowed him to sleep through lectures. At night time, he was invariably with his friends on Independence Square, propping up what he thought was a flagging protest.

“It looked hopeless, and there were only about three dozen of us on the square on that first week,” he says. “But then, right as we were sleeping, the police attacked us, and the rest is history.”

With bruised and broken limbs, the group of students somehow scrambled their way up the hill from Independence Square to find refuge at St Michael’s Monastery. The next day, hundreds of thousands turned out to protest Yanukovych’s violent turn. This was the moment Maidan ceased being a protest about the EU, says Ratushnyy, and became a rearguard action “to stop Ukraine turning into a Belarusian dictatorship”.

As the stakes and threats of violence increased, the revolution transformed the lives of those who took part. It broke some, with mental heath a huge issue during and after the revolution, and it made others.

It looked hopeless, and there were only about three dozen of us on the square on that first week

Roman Ratushnyy, protester

One of the breakthrough personalities of the revolution was a young journalist called Nataliya Gumenyuk. By coincidence, she was part of a group of independent journalists who had planned to launch a new public broadcaster the very week protests broke out. At the start, the team harboured vague aspirations about becoming a “Ukrainian BBC,” but as the protests progressed there ceased to be any question as to its purpose. The journalists of the new Hromadske Telebachennya ["Public TV"] became brave chroniclers of the revolution, working under considerable risks. Gumenyuk was the channel’s most recognisable face, a charismatic anchor and occasional field reporter, her tiny body and outstretched microphone darting between the black tyres and tarpaulin tents of the Square.

Hromadske brought forward its planned soft launch to carry rolling coverage from the second day of protests. Gumenyuk, meanwhile, flew to the Vilnius summit to cover the failed negotiations with the EU later that week.

She remembers a “surreal” sense of trepidation as she boarded the plane back to Kiev. The aircraft was packed with the familiar faces of journalists, activists and politicians, she says, but there was a “horrible atmosphere” on board. News of the violence against students had already filtered through. People understood a rubicon had been crossed, but they had little idea of what would come next, and there was certainly no leader to pick up the baton.

“For a large part of the Maidan revolution, professional politicians were two or three steps behind the people,” says Gumenyuk. “I remember a briefing held by [then opposition leader, future Prime Minister Arseniy] Yatsenyuk in Vilnuis, who said it was time to end the protests and wait for elections to dispose of Yanukovych. We tried to tell him it wasn’t in his power to tell the people to leave.”

The protest ultimately chose its own, revolutionary path, and not every step along the way was beautiful. As Maidan moved to its more militaristic phase, the democratic ideals that motivated the original EU flag-waving activists to the streets often seemed far away. The flags changed. In place of the yellow stars of Europe came the black and red of the Second World War anti-Soviet partisans, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

While the nationalist militias that flew these flags may never have represented the majority of protesters, they were certainly its loudest and strongest. In the last weeks they were a key cog of the resistance. When, for example, protesters detained “titushki”, the Yanukovych-hired thugs who intimidated Kiev for weeks on end, the task of administering "justice" was often handed to right-wing radicals.

“It’s true that the nationalists went further than they needed to, and not only with the titushki but with anyone they didn’t take a fancy to,” says Ratushnyy. “No decent person would have felt comfortable in the midst of their headquarters in the Kiev municipal building.”

In the months that followed, as a shell-shocked nation came to terms with its revolution, these nationalist groups claimed a chunk of the political vacuum. To this day, they continue to occupy key positions in and around government, and without clear popular legitimacy. The interior ministry’s links with the far right continue to be one of Maidan’s most troubling legacies.

Five years on, it is sometimes difficult to see progress on some of the issues that galvanised protesters. The Ukrainian economy is still largely under control of a handful of oligarchs, even if the most powerful have lost some influence. The prosecutor’s office is still used as a political weapon, not least against independent journalists. And the forthcoming – undoubtedly dirty – election cycle may well bring one of Ukraine’s old guard, Yulia Tymoshenko, to the presidency.

Tamara Kemskaya says the lack of real change has been “painful”.

“The blood has flown, my son’s blood, but the change we were fighting for hasn’t quite yet come,” she says. “We have the same corruption, and practically no one has been punished for their crimes.”

Then there is the matter of what followed the revolution. Within a few months, the traumatised country would face see Crimea annexed and a war begin in its eastern regions. That war has split the nation and cost more than 10,000 lives with little end in sight.

For journalist Nataliya Gumenyuk, however, it is wrong to judge Maidan exclusively by the events that followed. That chain was not determined either by the protest movement or by Ukraine, she says, but by “a combination of Russian counter-revolution and western inaction”.

“The west always did too little too late, and had to be begged to do anything,” she says. “Yes, the Ukrainian government carried responsibility for failing to engage with populations in the east, but the west also failed them too by failing to establish a cost for Russian aggression. They were always worried about the cost of sanctions.”

For all the pain, Gumenyuk believes the Maidan revolution will eventually be seen as a victory for Ukraine. What it did, she says, was to “pull Ukraine away from a post-Soviet course” and propel new faces into the Ukrainian government.

“Had nothing happened, we’d be on the same vector as Kazakhstan or Azerbaijan: old, authoritarian, post-Soviet,” she says.

“Five years on, you really can say Maidan was worth it. The tragedy was the war.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News