The forgotten maths genius who laid the foundations for Isaac Newton

On a cloudy afternoon in England in 1639, 20-year-old Jeremiah Horrocks became the first person to accurately predict the transit of Venus and measure the distance from the Earth to the sun.

His work proved, for the first time, that Earth is not at the centre of the universe, but revolves around the sun, refuting contemporary religious beliefs and laying the foundations for Isaac Newton’s groundbreaking work on gravity.

Yet today Horrocks has been “almost forgotten” and few are aware of the important contributions he made to the field of astronomy. Due to his untimely death at the age of 22, his work was never published in his lifetime and he never gained widespread recognition for his dazzling mathematical achievements.

“Without Horrocks, all the pieces wouldn’t have been in place for Newton,” said Dr Matt Bothwell, public astronomer at the University of Cambridge. “Yet he has been almost forgotten, except among history of astronomy buffs.”

Now, a new play, Horrox, will attempt to reassert Horrocks’s rightful place in history as a British genius who, according to the playwright David Sear, “changed the way we see the universe”.

“We had no idea of the scale of the universe until Jeremiah Horrocks,” said Sear. “He was the first person to prove that the Earth was not the centre of creation, destroying key precepts of Christian teachings and the primacy of a literal interpretation of the Bible in the process.”

Despite this, Horrocks’s great treatise on the transit of Venus was nearly lost for ever. Only a Latin manuscript survived the ravages of the civil war and the Great Fire of London. Passed from one astronomer to another for 20 years after Horrocks’s death, it would not be published until 1662, in an appendage to a Polish astronomer’s work.

“Nobody understood the significance of Horrocks’s work until Newton picked it up,” said Sear.

Horrocks was only 20 when, in 1639, he made a crucial mathematical breakthrough: “He found an error in the maths of a very famous astronomer, Johannes Kepler, and corrected it,” said Sear.

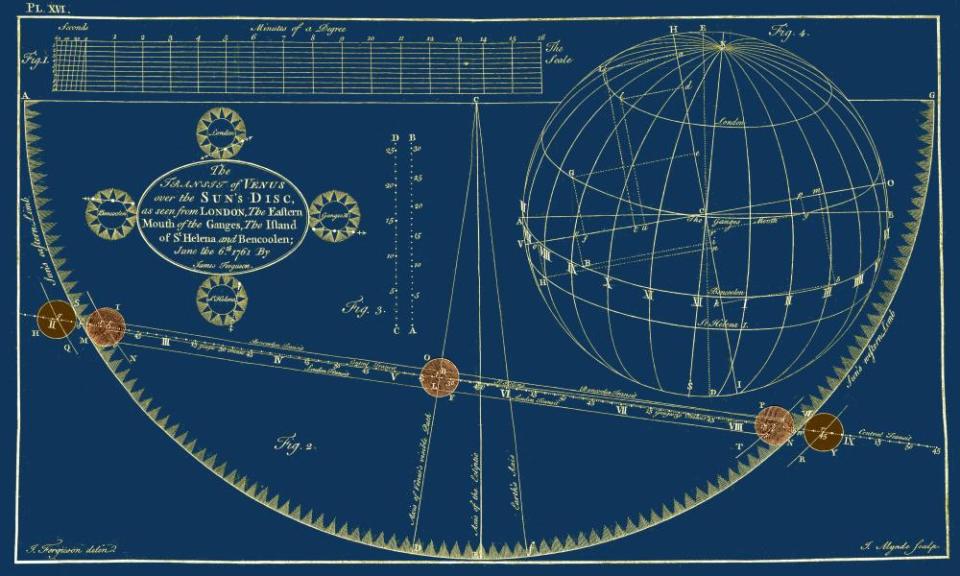

This correction revealed that the next transit of Venus would happen in a matter of days, and would not occur again until 1761. “Horrocks was the only person who knew it was going to happen,” Sear said.

He rushed to inform his friend and fellow amateur astronomer, William Crabtree, a draper from Manchester.

The pair had just enough time to coordinate, and seized the rare opportunity to observe Venus in silhouette from two different locations, enabling them to record vital measurements that had eluded other astronomers.

“The only way you could measure the distance to the sun at the time was by getting an object to fix on, between the Earth and the sun, and then triangulating through,” said Sear.

In 1687, Newton acknowledged the importance of Horrocks’s observations in his Principia: “Newton wouldn’t have been able to complete his work on gravity, if Horrocks hadn’t done these observations at the time he did,” said Sear. “Newton relied on this earlier work.”

Horrox, which will run in Cambridge’s ADC theatre from 28 March to 1 April as part of the Cambridge festival, begins in 1632 as Horrocks makes his way to university in the city on foot. Sear said: “At the age of 14 or 15 – no one’s quite sure – he walked to Cambridge from Lancashire, to study the stars.”

The son of a watchmaker, who was largely self-taught, Horrocks worked as a sizar while studying at Cambridge, serving his fellow students and even emptying their bedpans to pay his way. “He begged and borrowed books from the various Cambridge colleges, and left without a degree, probably because he’d run out of things to read,” said Sear. “We would be looking at him as some kind of child phenomenon today. At his age, understanding the maths he did, making these amazing observations on rudimentary telescopes and then drawing conclusions that overturned established religious and scientific beliefs about the nature of the universe – he was a genius and 400 years ahead of his time.”

Related: The private lives of Isaac Newton | Sarah Dry

He thinks the key reason Horrocks has not received the recognition he deserves is because “he committed the sin of dying young”. This meant Horrocks did not have a chance to publicise his work and gain the respect of his fellow astronomers, and so was not publicly lauded for his discoveries the way Kepler and Galileo were.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News