A Former CIA Interrogator on Death, Torture and the Dark Side

Warning: This article contains graphic images.

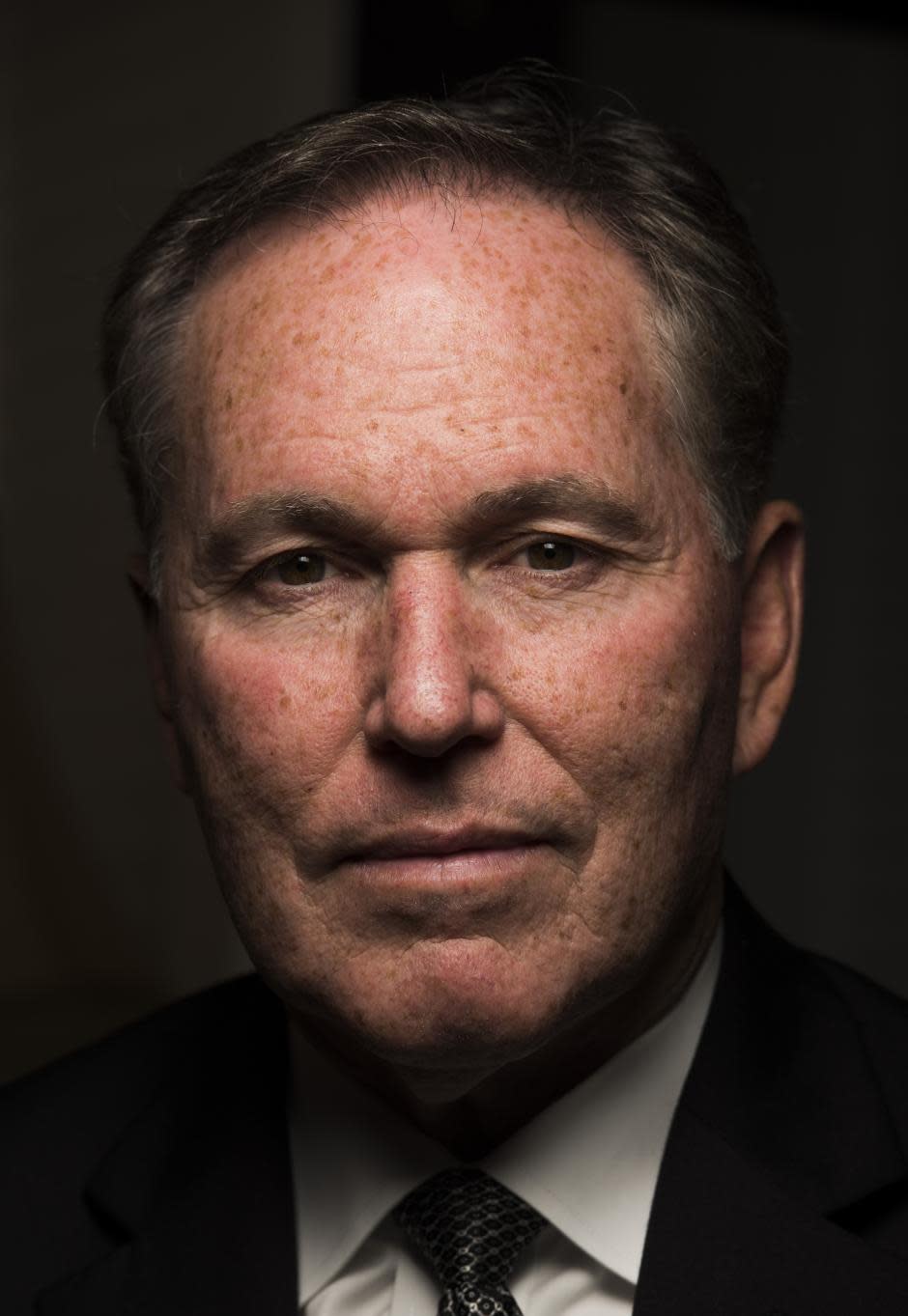

When David Martine arrived at the redbrick federal courthouse in Alexandria, Virginia, in the summer of 2011, he was three years past his retirement and had not participated in an interrogation since 2007, when he was one of the CIA’s top inquisitors. On this day, however, he was not going to be asking questions. He was going to be answering them.

The Obama administration was investigating the deaths of prisoners in CIA custody. An earlier probe into a CIA official’s order to destroy interrogation videos taped at “black sites” around the globe had failed to result in indictments. But expectations were high among critics of the agency’s “enhanced interrogation techniques” when John Durham, a celebrated special prosecutor, began issuing subpoenas to CIA officers linked to the deaths. Martine was near the top of his list. As chief of the CIA’s Detention Elicitation Cell in Iraq, he was suspected of destroying evidence connected to the grisly 2003 death of “the Iceman,” an Iraqi detainee whose ice-packed corpse was spirited out of the infamous Abu Ghraib prison with an IV jammed into it as if he were still alive.

It was hardly the first time Martine had been questioned about the incident. The CIA’s inspector general had repeatedly probed him and others at the spy agency about the fate of the Iceman and other captives in Afghanistan and Pakistan. And as Martine entered the courthouse, he, like other interrogators before him, was outraged that the cases had dragged on without resolution. “It was very discouraging,” Martine tells Newsweek in an exclusive interview, the first time a CIA interrogator has discussed the Iceman case or his grand jury testimony publicly. “I had been investigated for seven years.”

For the next year, Durham continued to pursue a criminal investigation into the deaths. Then, in June 2012, Attorney General Eric Holder announced that the Justice Department was closing the cases because of inadequate evidence. The upshot: After the demise of at least three detainees in CIA custody and more than 100 other prisoners held by U.S. forces, few were ever charged and even fewer convicted. “Wars are messy by their very nature,” Michael Pheneger, a retired Army intelligence colonel who reviewed many of the cases for the American Civil Liberties Union, told the Associated Press in 2007. “But it's perfectly obvious that there is no rule of engagement that would authorize someone to kill someone in custody.”

Related: Beyond Torture: The New Science of Interrogating Terrorists

The fate of the Iceman, said to be buried in an unmarked grave in a vast cemetery 100 miles south of Baghdad, is one of the many troubling mysteries in the war on terror. Barack Obama campaigned on dramatic pledges to cauterize the messy edges of the conflict “on the dark side,” as Vice President Dick Cheney called it. President Obama denounced the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation techniques” as torture and signed an executive order to close the U.S. prison at Guantánamo Bay as one of his first acts as commander in chief. Today, for all anyone knows, Guantánamo could remain open indefinitely. The cases of the five surviving 9/11 conspirators, as well as those of other top alleged terrorists, remain unresolved. And the government, not to mention the public, is still divided over how to sweep up, hold, question and prosecute foreign terrorists.

Despite the profound differences between the prisoners and CIA interrogators, there is a bizarre parallelism between their unresolved fates. Many of the prisoners, according to recent investigations, were minor Al-Qaeda functionaries. A few were child soldiers swept up from the Afghan battlefields in the post-9/11 chaos. After more than a decade, m any seem slated for indefinite detention without trial. Most have never been charged with a crime or never been cleared. Likewise, though free, Martine and others like him have not been charged or had their names cleared either. Today, both the interrogators and prisoners remain stuck in a disturbing limbo. And so too are the American people. For them, the identity of whoever was responsible for the deaths of prisoners and other serious crimes remains a lingering, bloody question mark.

Hiding the Body

Early on the morning of November 4, 2003, a team of Navy SEALs with CIA support captured an Iraqi by the name of Manadel al-Jamadi. U.S. intelligence suspected him of being involved in the bombing of the Baghdad headquarters of the Red Cross, one of five synchronized attacks that killed 35 people and wounded 244. Jamadi resisted violently and suffered what an autopsy later determined were three broken ribs. Before dawn, the injured, manacled captive, naked from the waist down and with a bag over his head, was seen being led into Abu Ghraib prison. A “ghost prisoner,” like many in CIA custody, Jamadi’s presence was never recorded in the facility’s log. Roughly an hour later, he was dead.

A military policeman later told investigators that the sole CIA officer in the shower area at Abu Ghraib where the prisoner was chained, Mark Swanner, had asked him and another guard to hoist Jamadi higher on the wall. That despite the fact that his arms were already “almost literally coming out of his sockets,” one of the soldiers told investigators. “I mean, that’s how bad he was hanging. The...[CIA] guy, he was kind of calm. He was sitting down the whole time. He was like, ‘Yeah, you know, he just don’t want to cooperate. I think you should lift him a little higher.”

Related: How a Botched Translation Landed Emad Hassan in Gitmo

The autopsy report called the death a homicide, the result of “blunt force trauma” and “asphyxiation.” But of the 10 Navy SEALs involved in the capture of Jamadi, only one, team leader Lieutenant Andrew Ledford, was tried in a military court, and he was acquitted of striking the prisoner and lying to an investigator, among other charges. The CIA referred Swanner to the Justice Department, which declined to press charges. But in 2011, he was called before Durham's grand jury. Swanner has consistently declined to comment on the incident.

Martine, who was asleep in Baghdad’s secure Green Zone when Jamadi was captured, says he got a call from Abu Ghraib telling him of the prisoner’s death around 4:30 a.m. He says he rushed out to confer with CIA colleagues and U.S. military personnel guarding the facility. The former CIA man concedes that the agency and the Navy SEALs who captured Jamadi bear some responsibility for his death because of the basic fact that he died in their custody. “When you ask that simple question, Did we cause this man's death? That's a simple answer—yes,” Martine tells Newsweek. “But were we negligent in causing his death? I don't think that we were.”

Martine also concedes that the CIA inspector general held him partly responsible for the decision to ice Jamadi’s body, preventing its deterioration until CIA and military personnel hatched a scheme to hide the death: They taped an IV to the frozen corpse, which made it look like the prisoner was still living as they smuggled the body out of Abu Ghraib, steps that led many to suspect a cover-up. Martine acknowledges that, in fit of wartime dark humor, he dubbed Jamadi’s corpse “Bernie,” a reference to the comedy Weekend at Bernie’s, in which the body of a man is marched around by his friends as if he were still alive. “I suppose a lot of people would think that was callous and disrespectful,” he says.

Another major issue was the nylon bag used to cover Jamadi’s head. Once he died, the hood was removed and blood came gushing out of his mouth “as if a faucet had been turned on,” according to the testimony of a guard. Then it disappeared. Martine says a CIA security officer gave him the hood days later, when it was found in the van used to transport the body. Martine says he placed it in a plastic bag and “threw it” on a shelf in his Green Zone office. Months later, in a rush before he returned to the U.S., he says he tossed away the reeking bag. With that, the case may have dissolved into a footnote. But then the notorious Abu Ghraib prison scandal erupted with its gruesome photos of American soldiers humiliating and abusing Iraqi prisoners. Several showed soldiers grinning with a thumbs-up sign over the Iceman’s battered corpse as if it were a hunting trophy.

The hood would later emerge as a centerpiece for allegations that Martine destroyed evidence. It was a big, stinking clue for Durham. During Martine’s six-hour grand jury appearance in 2011, he says, the prosecutor asked him, “If the hood wasn’t important, why did you keep it on your office shelf? And if it was important, why did you throw it out?”

Martine admits it was “a good question.” But Durham’s questioning became even more contentious, he says. “He just kept pushing and pushing.… ‘Why are you hiding things, and what else should you be telling us?’ I mean, I didn’t know what to say.” His answer then and now: There was no formal investigation that he knew of at the time, and he was never asked about the missing blood-stained shroud until much later. Another CIA officer who was also repeatedly questioned about the Iceman incident snapped, Martine says.”At one point, he said—and they used this against him—‘I wish we had just killed him, because then I could just say he deserved to die.’”

Despite Durham’s aggressive questioning, Martine says there was no conspiracy to cover up Jamadi’s death. He admits he helped plan the smuggling of the body out of Abu Ghraib. It made “perfect sense,” he says, to conceal his death from other captives, who might have erupted into “an immediate riot” had they known of the prisoner’s demise at the hands of the Americans. But he says he never concealed the events from the CIA or from the U.S. military. “We were never hiding this from our chain of command, either military or agency,” he says. “It was not a covert op.”

Related: U.S. Develops New 'Soft' Techniques To End Torture

Perhaps, but Martine also edited and filed a report to CIA headquarters that omitted classified details of the Iceman’s death that some thought he should have included. To Durham and others, it appeared he might have been involved in a crime, suspicions that follow Martine to this day.

‘You Could Twist This’

A handsome man wearing a Rolex and sport shirt, Martine, 59, appears tanned and relaxed as he drives his black Mercedes SUV to the lakeside Erie Yacht Club in Pennsylvania. Erie is the town where he grew up, where his father was a school principal and his mother a school counselor. In the dining room, friends and fellow club members greet him warmly. He seems eager to show that the controversies surrounding his role in the war on terror did not follow him here.

Yet as the former chief of overseas polygraphs, interviews and interrogations labors through the details of his story, it’s clear he remains troubled. The multiple investigations, he says, have wrecked long friendships among the interrogators, because they were forbidden to talk to one another, lest they be accused of coordinating their testimony—“the conspiracy thing,” as he calls it.

Sitting at a table in the crowded dining room, Martine explains why he is talking with Newsweek. “I want this to go public,” he says. “I never employed hard physicality as a method of interrogation.”

“You know, this story could go either way,” he adds, ignoring the menu placed before him. “You guys could leave here saying, ‘That guy is hiding information. They did cover this up. There was a murder.’” Opening up to a reporter risks his “wonderful life here, with a great family and great friends and a great career,” he says. “You could twist this in a way that there would be a dark cloud that would follow me forever.”

Martine first invited attention in 2011, when he outed himself as a former interrogator in a little-noticed article in his local newspaper in which he volunteered he had been subpoenaed to appear before Durham’s grand jury. “If we crossed a line, I am part of that,” he was quoted as saying, “but I think I am asking the same question everyone else is: Why are they doing this again?”

Durham’s probe of the CIA ended not with a triumphant press conference but in a puzzling silence. Once described by a friend as seeing the world as “good vs. evil,” the resolute prosecutor of Mafia thugs, politicians and corrupt FBI officials had waded into the CIA’s many shades of gray and emerged empty-handed. Whether he asked jurors to indict Martine or any of the other CIA targets remains unclear. Only years later did he issue a little-read statement, in response to a Freedom of Information lawsuit, detailing, without further explanation, the procedural steps underpinning his decision not to file charges. Contacted by Newsweek, Durham declined to comment.

Martine says the outcome was disappointing. “It’s certainly not been a good moment for me,” he says. “Not that you expect to come back a hero, but you expect to come back with a semblance of respect and a, ‘Hey, job well done.’”

That’s not going to happen. And so now, years later, Martine seems to be seeking a kind of public exoneration. “I feel I can stand up and tell of every procedure I have employed,” he says, “and I think America would stand behind me.”

‘Torture Works’

A large red, white, green and yellow Kurdish flag hangs on the wall behind Martine’s desk at Gannon University, a small private Catholic college in Erie where he teaches courses on criminal justice and terrorism. “The princes gave it to me,” he says proudly, referring to the sons of Jalal Talibani, the legendary Kurdish independence leader and politician. “They wouldn't be too pleased to learn we did interrogations in their parents’ basement,” he adds, chuckling. “The younger one wasn't supposed to be involved.”

Years earlier, Martine’s unlikely path to becoming a senior CIA interrogator began with an arrest—his own—as a 13-year-old, when he took a ride in a “borrowed” car with some teenage buddies. A probation officer “set me straight,” he says, launching his fascination with police work. At the University of Dayton in the late 1970s, he got a job as a campus cop to help defray college expenses, eventually snagging an internship as a juvenile probation officer. Then, equipped with a degree in criminal justice, he applied to the FBI. Within a few years, he was an evidence technician scouring for clues at the site of John Hinckley’s assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan. Along the way, he earned a master’s degree in forensic science from George Washington University, took graduate courses in psychology at the University of Virginia and had thoughts of going on to law school to qualify as a full-fledged FBI agent.

But when his wife’s pregnancy forced him to abandon the idea, he followed a tip from a friend about a job at the CIA. Soon he was headed up the Potomac to Langley, Virginia, and a dramatic new turn in his career, as an undercover agent in the spy agency’s office of security. The job involved the sometimes harrowing work of moving defectors from place to place, but it also took him to Latin America, Africa and the Far East on a range of security assignments. Eventually, he became a senior CIA training officer in polygraphs and interrogation, “and most of that work was done in South America.”

The region was plagued by war. Military regimes, most backed by Washington, ruled most of the continent. The secret police of Chile, Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil were conspiring in assassinations of local leftists and dissident exiles. The CIA was helping prop up the brutal dictatorships of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador while fielding a guerrilla army to bring down the Marxist regime next door in Nicaragua. The casualties in El Salvador’s civil war were catastrophic, with 70,000 to 80,000 dead, 8,000 disappeared, about 550,000 internally displaced and another half-million in exile. “It was an exciting time in Central America,” Martine says, at least for his career.

Latin America also was where he began to conclude—his assessment reinforced by assignments to U.S.-client regimes in the Middle East and Asia—that “torture works.” “No one wants to be honest about it!” he volunteers in an email. “Torture has always worked.”

Not that it’s right, he quickly adds. But it’s wrong to say it’s inefficient (as FBI interrogators have argued). The false confessions and phony leads prisoners give up under excruciating physical and psychological abuse are not a big problem, he insists: You just check them out. “If we are talking torture, and I mean real torture, where we are going to start taking off fingers or you're going to saw off his foot...they will tell you anything you want to hear,” he says. “You tell them that if they give [you] false information, you'll be back the next day sawing off their other foot.”

“They are not going anywhere,” he says. “So you have tremendous control over this person's tolerance for pain—they are going to give you everything they know…. It's just a matter of when. If you're willing to burn out an eye and then say, ‘We're going to check all this, and tomorrow we'll burn out your other eye,’ people are going to tell you everything that they know.”

So where did he learn firsthand about the efficacy of torture?

The question seems to take him aback. "The only experience that I would have from that is from some of the things that we had come in later,” he says vaguely, declining to discuss classified specific cases. “Now, obviously, if it’s torture with any country, we backed out,” he adds. “But when you see how some people are treated in other dungeons and other controlled areas...” He shakes his head.

And he personally had seen that?

“I have, of course, of course.”

Where? In the prisons of U.S. allies known for their brutality, like, say, Egypt?

“Sure,” he says. “And in Central America. And in South America.” Prisoners told him about it afterward, he says.

Given his job, such conversations probably didn’t take place too far from the torture chambers. But it’s a distinction without a difference, according to Michael Scheuer, who headed the CIA’s Osama bin Laden tracking unit from 1996 through 1999. “There were no qualms at all about sending people to Cairo” and other brutal places to be interrogated, Scheuer told a congressional panel in 2007. There was a “kind of joking up our sleeves about what would happen to those people in Cairo, in Egyptian prisons.” The CIA merely picked up the fruit the Egyptians had shaken from detainees, he said.

Such practices, of course, allow CIA people like Martine to distance themselves from torture and profit from its supposed benefits. Torture is unworthy of America, he says. And he insists it was rarely employed by the U.S., even in the years immediately following the 9/11 attacks, when “the interrogations of CIA detainees were brutal and far worse than the CIA represented to policymakers and others,” according to last year’s Senate Intelligence Committee report. “I don't think we get the credit deserved,” he says, “for standing on the right side of humanity in our treatment of all those in our custody.”

This sunny statement contrasts violently with the brutal death of the Iceman. It also provokes derision among those who know what went on in CIA black sites or military-run jails. One of the most prominent is former FBI senior counterterrorism supervisory agent Ali Soufan, who famously denounced the CIA’s repeated waterboarding over a period of months of low-level Al-Qaeda functionary Abu Zubaydah, until he “confessed”—falsely—that he was a top operative in the militant group, Soufan has testified to Congress. “I cannot believe that in the United States of America, we are still debating if torture is a good idea or not, or if it is effective or not,” Soufan says. “Really—in America!”

Martine disagrees—to a point. It’s “wrong,” he says. But despite the damage the exposure of torture inflicted, and continues to inflict, on the United States, he says the CIA should never take the threat of it off the table when it rounds up a terrorist suspect. “If they're thinking, They got me in the middle of the night, and they are taking me to a small dark room, and they are going to blow my brains out—I think that that may save lives. In reality, we're not gonna. [But] we're going to put on a little scary reality show for them.”

Soufan dismisses such talk. He points out that the Senate Intelligence Committee’s 6,300-page investigative report on the CIA interrogation program, “not to mention all other reviews, such as the CIA's own inspector general report, all came up with the same conclusion: Torture does not work and is harmful to our national security.”

Even former CIA acting General Counsel John Rizzo, who argues that the multiple investigations into agency interrogators should have been dropped long ago, says the CIA’s interrogation mess in Iraq could have been avoided had agency personnel followed these instructions: “Don’t hold prisoners yourself,” he said in a 2012 interview with the Constitution Project, a bipartisan watchdog group based in Washington, D.C. “Defer to the military on questioning. Only participate when invited to do so. Don’t try to force yourself into these interrogations.”

Yet the CIA constantly thrust itself into the interrogation front lines, such as when Martine followed U.S. invaders into Iraq in 2003 in search of Saddam Hussein’s much-advertised (but nonexistent) weapons of mass destruction. Soon he found himself face-to-face with the notorious “Dr. Germ,” Rihab Taha, the woman who headed Iraq’s biological warfare program. “I cracked her deputy,” Martine says. “In fact, we went under a sink in his home and found a biological pathogen.”

But the boss lady was different. “She was mean, and she was uncooperative,” he says. To survive under Hussein, she had to be tough—and smart. “And she knew, as a female, she could win this,” Martine says. “And she did.” By “as a female,” he implies that women captives escaped the rough stuff meted out to men. And he didn’t lay a hand on her, he says. The result: Taha virtually talked him to death. “She was very measured, and she had her lines, and she never moved from those lines.” He seems to regret that he couldn’t have been more forceful. “With her, I still feel to this day, 100 percent, that there was much, much more information that she could have offered to us, and she chose not to.” Instead, “she was released,” he says with some disdain. And where is she now? “Living in Iraq somewhere, probably.”

‘Forced’ to Do Ugly Things

And the Iceman—what happened to his body? Martine doesn’t seem to know or care. “Got me,” he says.

Just another unresolved case, in his mind. And, ironically, very much like his own—although he has the benefit of being alive and free. The same cannot be said for the 114 prisoners languishing in Guantánamo, the first of whom arrived more than 13 years ago. More than 50 of the inmates have long been cleared for release. Roughly 50 more will apparently not be tried but are considered too dangerous to be set free and could be detained indefinitely. Finally, there is an alleged core of Al-Qaeda operatives facing military trials that, after many years, still show few signs of getting off the ground.

Indeed, the legacy of the torture years remains mired in ambiguity. While John Helgerson, the CIA’s inspector general from 2002 to 2009, reportedly made eight criminal referrals to the Justice Department for homicides and other misconduct carried out by CIA interrogators, none resulted in indictments or statements that the accused had been cleared of wrongdoing.

All of which is manifestly unfair, says Martine, even though prosecutors have no obligation to “clear” anyone they investigate. After Durham went home, the Justice Department said only that “the admissible evidence would not be sufficient to obtain and sustain a conviction beyond a reasonable doubt”—hardly a benediction. And although Martine and others have never come close to being publicly exonerated, he and his colleagues need not worry about being summoned back to the redbrick courthouse in Alexandria. They may even have gotten off easy—especially since the published photos of the Iceman’s battered corpse produced months of horrible worldwide publicity for the CIA and the United States.

Yet Martine insists the case against him and the others was “political.” “Certainly,” he says, Obama and Holder “wanted to deflect and put this back on [President George W.] Bush.” He compares himself and those who were ordered into the murky war on terror to veterans of Vietnam, upon whom history’s kindest judgment seems to be that they were forced to do ugly things. “And we come home, and they can sort of pursue something like this, over and over again over the years,” Martine says.

In the warm fellowship of the Erie Yacht Club, Martine may remain a hero to many, even as a large body of critics continue to view anyone associated with the CIA’s “enhanced interrogations” as monsters. Other Americans have simply moved on, leaving Martine and those like him hostage to their consciences and the judgment of future generations.

Case closed: unresolved.

Related Articles

Yahoo News

Yahoo News