Goldman Sachs' new initiative will courier working mums' breast milk to their babies across the world

Goldman Sachs is the investment bank with a hardcore reputation. It’s the employer which, it used to be said, gave staff only four hours off for bereavements — and two weeks for giving birth. Get a job at Goldman and your life belongs to Goldman.

But now it’s 2018, and even Goldman Sachs has gone family-friendly. The bank that once told staff their weekend ended on Sunday morning and they’d better be logging in again by then, and which is known for offering graduates six-figure salaries to compensate for 100-plus hour weeks, has changed.

The latest evidence? The US bank has become what’s thought to be the first company in the UK to pay for its breastfeeding working mums to courier their expressed milk back to their babies if travelling for work.

In an internal memo to staff, the bank said: “Parenting and work can sometimes feel at odds. Goldman Sachs aim[s] to make the balancing act a little easier,” before explaining that its US offices will deliver freezing kits to nursing bankers’ hotel rooms and then courier expressed milk back to the baby for feeding.

For bankers in London, where Goldman employs 6,000 people, new mums will be reimbursed for breast milk delivery costs on work trips.

“Cynics,” one female banker at the firm told me, “will say this is just to get mums back to their desk as soon as possible. But Goldman really is good to women now — it offers six months’ full-paid maternity leave and doesn’t pile on pressure to return before that. Most take nine months.”

Truth is, the cynics will probably be right. “Long-term greedy” is how Goldman’s legendary managing partner Sidney Weinberg once summed up the bank’s overarching strategy. It faced a high-profile lawsuit in 2015 when Sonia Pereiro-Mendez, an executive director at Goldman’s Fleet Street HQ, claimed managers underpaid her by £1.4 million after she became a mother, and created a culture where she had to breastfeed in a car. Goldman settled the case out of court but hated the publicity it threw up.

Now the US bank’s culture has changed — because it had to. “Goldman may have succeeded in luring young graduates to work seven-day weeks,” an industry recruiter tells me, “but — as with all investment banks — its more senior staff wanted to see their families. The bank could lose them to more flexible firms — especially in tech, or change its culture to keep their talent.”

Goldman was one of the first corporates to introduce “lactation rooms” for women to express breast milk; it runs free pre-natal fitness classes at its office gym and has on-site daycare — the only one at any bank in the Square Mile — where chests of toys, a climbing wall and qualified staff look after employees’ children for 20 days each year for free. Yes, that keeps its staff at their desks — but it also solves the average working parent’s endless childcare crises.

Goldman’s milk-shipping is its latest parental perk. It’s not a new concept: IT giant IBM, social network Twitter and consultancy Accenture are among those that offer the service to staff in the US.

Since it’s the only country in the developed world without state-paid maternity leave, working mums go back to the office far earlier in the US than in the UK, where employees receive pay for 39 weeks.

But American moms breastfeed for longer: more than half are still breastfeeding when their babies are six months old, compared with 34 per cent here. So US corporates pay to help nursing mums who need to travel, when ceasing breastfeeding will stop the supply, but expressed milk won’t keep for long.

That’s what inspired Kate Torgersen to set up her milk-shipping business Milk Stork in the US in 2014: back at work after maternity leave after having twins, she says she “didn’t want a business trip to derail the huge efforts I’d made to tandem breastfeed.

"But that meant pumping two gallons of breast milk while I was away and keeping it in a hotel mini-fridge — then packing it into an ice-filled cooler bag and lugging a sloshing, dripping suitcase of milk through airport security and its embarrassing inspection process, justifying to several security agents why I had so much breast milk.”

So Milk Stork provides pharmaceutical-grade shipping coolers to breastfeeding mums on business trips. They express, activate the cooler and call FedEx to, as Torgersen puts it in American, “have the milk overnighted home”. It costs about $100 per travel day — but Milk Stork is an employee benefit at US firms stretching from Nissan to retailer Home Depot and software giant SAP.

So far this year the company has transported 500,000 ounces of breast milk home to babies.

One user, writer Katie Baker, who used Milk Stork during a three-day business trip, told The Cut it meant “I didn’t have to schlep around to seek out dry ice and shipping materials on top of [pumping and] everything else; it definitely was a stress-reducer.”

That’s not the only way companies are helping nursing mums: Bank of America-Merrill Lynch has a “Maternity Room” for pregnant staff to rest or nursing mothers to express milk.

Kim Coussell, who works on the fixed-income sales desk at BoA-ML, says she finds it “a relaxing escape from the busy trading floor. It’s been such a blessing during my pregnancy and has also enabled me to meet other working mums-to-be.”

US law firm White & Case also has a room where mothers can express milk or feed their babies, who are bought in by the nanny — “and only nursing women have the key”. The culture has changed fast at law firms: another former Magic Circle legal exec who had her first child six years ago says: “I went back to work after five months, while still breastfeeding, but I didn’t want to re-emphasise the mummy thing. So I’d secretly book meeting rooms and sneak in to pump.”

Morgan Stanley this week started offering staff childcare at a nursery minutes from its Canary Wharf HQ, “where parents can visit their children at any time, or spend time in the dedicated breastfeeding rooms and soft-play zones”. It will also pay for an emergency nanny or nursery place for “back-up childcare” for 150 hours per child per year.

At the Mayfair office of Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, NBIM, there’s more emphasis on children actually getting to see their parents. Rather than paying for help, it gives both mums and dads extra time off to settle their kids into nursery and school, and gives 10 days of leave each year to staff with children under 12 to look after their sick kids.

The initiatives are often tied into corporate gender-equality targets: Twitter, for example, introduced its breast milk shipping scheme shortly after announcing aims to boost the percentage of women on its staff; Accenture did the same.

Some American companies’ parental benefits even include such things as surrogacy reimbursement and egg-freezing — the latter famously offered by Facebook, Apple and Google. Companies see these “perks” as a relatively inexpensive way to recruit and retain skilled staff.

Back at Goldman, it’s just after 6pm and the bank’s in-house children’s summer scheme is winding up. I’m imagining a vampire-squad indoctrination camp where bankers’ offspring learn how to increase their pile of Duplo while the kid next to them goes without.

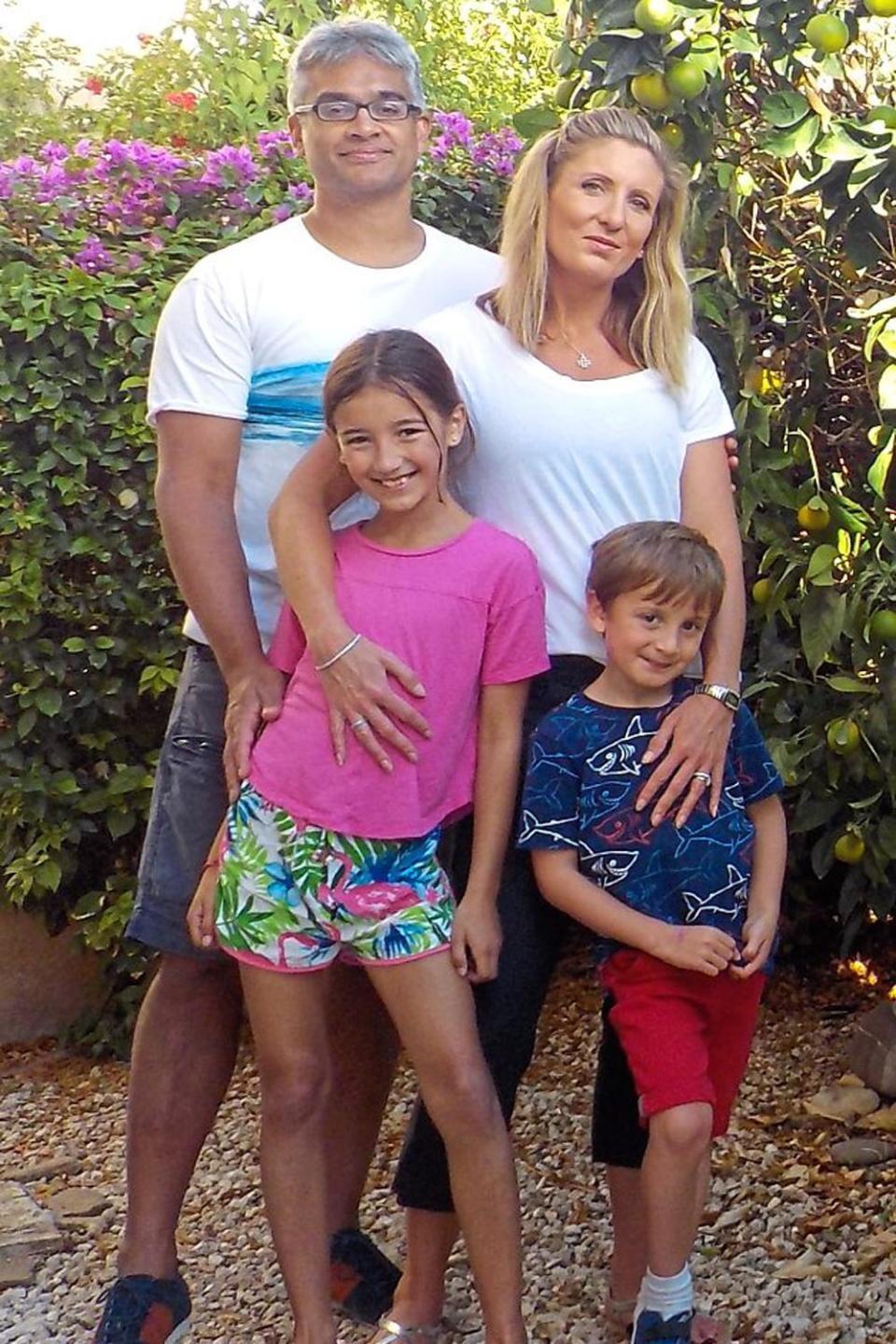

But Emma Pape, an executive director in wealth management whose kids, aged six and 11, use the holiday camp each year, says it’s actually games, Wii-playing and trips to the library, playgrounds and St Paul’s Cathedral. “The kids love coming into the office and seeing where I spend my life,” Pape explains.

“When I joined Goldman 15 years ago, it felt much more male-dominated. Now there’s a realisation that people have lives outside the office; you often see parents wandering around with their little ones.”

It’s not all change at the bank with a reputation for being the hardest taskmaster in the City, though. “This is a tough place to work. You have to be resilient and competitive, and it can be really stressful. I’ve pulled over-nighters when I need to. But women used to leave Goldman because they felt they couldn’t be an MD [the hallowed managing director status] and still have a family — that’s no longer the case. They’re very conscious of mental health and resilience. They want women to come back to work — and are helping us do so.”

This is Goldman Sachs, so someone with a six-figure bonus will inevitably have worked out the exact profit to be made out of protecting employees’ mental resilience.

But this time the staff are profiting too.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News