The Guardian view on Mrs Merkel’s speech: ominous common sense | Editorial

Angela Merkel’s matter of fact statement that Europe can no longer wholly trust Donald Trump’s America – adding that this had become clear to her during the meetings on his European trip – is on one level unsurprising. Is there anyone who met the president on his recent foreign tour who felt better able to trust him as a result? There may be those, like the Saudis, who feel they got what they wanted from him, but not even they can feel they can rely on him. There is a horrible irony in the reported remarks of a “senior administration official” after the G7 meeting, that: “This was a summit in which the goals and priorities of the United States and the president really were felt deeply ... Mr Trump has changed the way many people around the world are thinking of these issues.” Yes, he has.

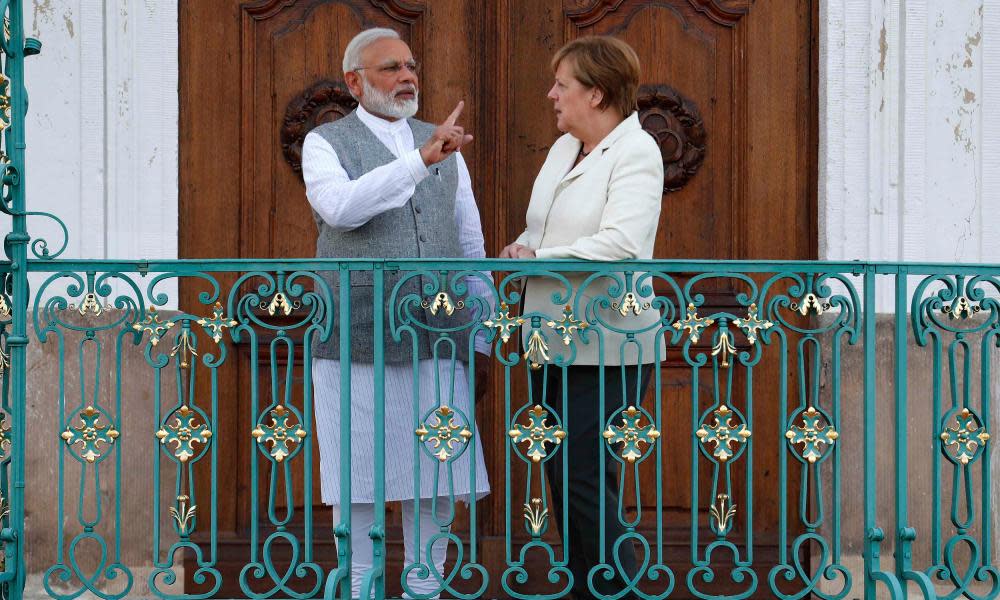

The change did not come overnight. It has been brewing ever since the election. In terms of internal German politics, Mrs Merkel was merely stating the obvious. The scorn and anger of mainstream German coverage of the Trump government is almost shocking: the magazine cover that portrayed the president as a terrorist who has beheaded the Statue of Liberty is only one example. The chancellor is fighting an election and she needs to protect her flank against the SPD to her left. She has said earlier that Europe must rely more on its own resources, too. But even if what she said was not itself a significant development, it was still one of those remarks which by their very ordinariness illuminate a significant change. It would not have been commonsensical five years ago.

Mr Trump shows no sign of acknowledging the existence of a world in which bullying and bluster won’t get him what he wants. After all, as he told a recent interviewer, he won the election and no one else did. In matters of domestic policy his style of slapdash aggression has already had some notable defeats. His wall is unlikely ever to be built. His first health care plan did not even make it to a formal rejection and the replacement is so cruel and meanspirited that even a Republican congress may fail to pass it. He shows no sign of the kind of attention to detail and capacity for concentration which is needed to bring about substantial policy changes. The scandals surrounding his connections with Russia will not go away. Yet none of this should comfort the Europeans. Politics, even international politics, is not a zero sum game in which the failures of one player automatically equate to success for another.

The failure of the US to live up to the illusions of those who loved it is a threat to the security and prosperity of both Europe and America and, in an interdependent world, to everyone else as well. Neither Europe nor America can hope to accomplish as much on their own as they could together. Neither, on its own, has the resources to do all that needs doing. When Mrs Merkel says that Europe’s destiny lies in its own hands, she cannot be entirely confident that these hands are ready to grasp it. An enomrous amount will depend on the effectiveness of her partnership with Emmanuel Macron, and it is no doubt significant that when the two of them met for supper during the G7 meeting, they were accompanied by their spouses. That shows on both sides a determination to establish the kind of personal understanding which is needed to make diplomacy work. But the EU does not have only two members who matter and Mr Macron does not even yet have a party in parliament. Bringing 27 countries together to recognise and grasp a common destiny will not be simple.

And what of Britain? The leap of faith that was Brexit now appears to be the kind of lunging step from a fixed, if rickety, jetty into a dinghy that turns out not to be moored to anything. In fact it is moving away from the jetty, partly pushed by our own careless step. We now have one foot on each. The gap is widening. One foot and probably both must slip. A rift between the EU and the US is very dangerous for Britain.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News