I work with hoarders. Forget the stereotypes

Since the World Health Organization classified hoarding as a mental health disorder last week, I’ve had an influx of calls and emails from all directions. This is to be welcomed as it means that hoarding can be taken seriously and treatments explored. My father was a hoarder – he grew up during the war, and remembered rationing and being hungry. After he died, it took four months to clear the family home. I recognised then that I wanted to work with people facing clutter issues. A year later I set up my own businesses to help.

The people who come to me are extremely varied – from young autistic men to retired engineers, as well as mothers struggling with family and clutter. I also work with people who are compelled to hoard information, which means that every telephone directory needs to be kept and every local newspaper piled up in the garage. Many hoarders are completely overwhelmed. My job is to help them manage their stuff and decide with them what they are hoping to achieve.

It’s about understanding the implications of their hoard, and how it is impacting on them, not about our own agenda

Some of our work can seem mundane but it can have huge knock-on effects. My team worked with one gentleman who wanted his granddaughter to stay for Christmas: this meant clearing the spare bedroom and the dining room (it wasn’t immediately clear that he had a dining room table). Once they managed to do so, his granddaughter was then able to visit regularly. We have continued to help him maintain his home.

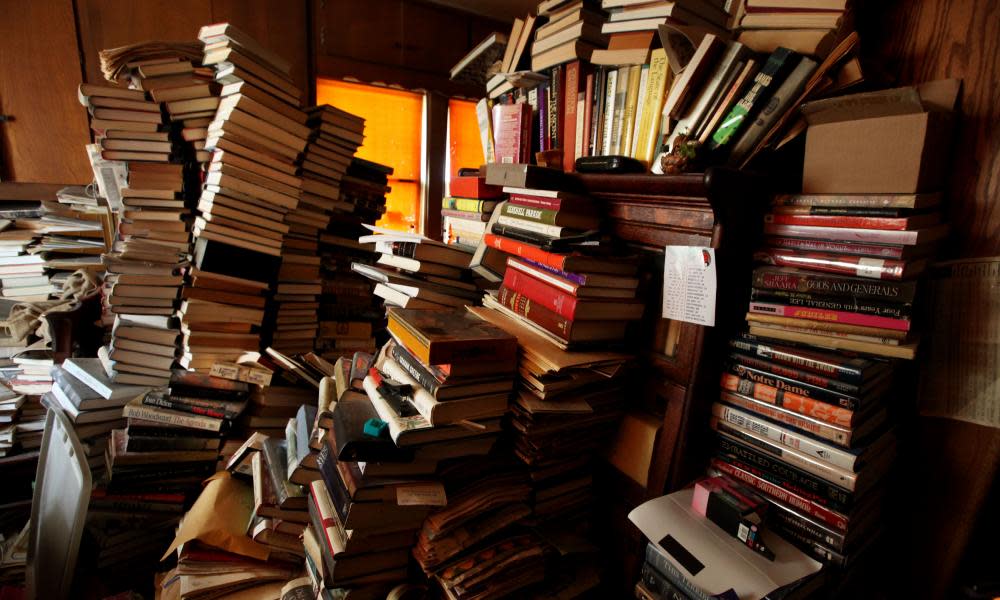

I think we all know someone who exhibits hoarding behaviours, but I know our attitude towards it can be quite narrow and closed. We may think, how they can live like this? And TV programmes about hoarding do nothing to reduce the stigma. There are also many preconceived views of the stereotypical profile. But not all hoarding is squalid and dirty – many with these behaviours are fully functioning yet challenged by their physical environments.

Now that hoarding has its own classification, we need to recognise that there are also those with chronic disorganisation whose houses might manifest as a hoarded home. For some they have not been given life skills to know how to maintain a home without clutter and for some it boils down to sheer laziness. Other underlying issues such as depression, ADHD and autism can contribute to a chaotic home.

It is invaluable to know the differences in these behaviours before diving straight into “help mode” with someone facing hoarding issues.

Establishing a rapport is vital: it has to be about the person first – their stuff is secondary. It’s about understanding the implications of their hoard and how it is impacting on them. It is not about imposing our own agenda or our own standards of living. We also know that hoarding can have fire implications so health and safety is paramount.

Hoarders hate landfill. Letting go and decluttering can bring feelings of being wasteful and frivolous. To some it even evokes a sense of disloyalty and abandonment to the objects that they have formed emotional attachments to. They often want to know that their belongings can be re-purposed. I work with a local charity to donate hoarded fabrics, wool, bedding, towels, toiletries – some half-used, some new.

The hoarder’s journey can be a long one – it takes years for a house to fill up: it doesn’t simply take a weekend clear-out to solve the issue. For several years I have run two hoarding support groups in Newbury and Bracknell, Berkshire. The meetings are held monthly and many people have been attending since the beginning. Those who come tell us that it helps to reduce the shame they feel, and makes them feel less alone with their challenges and less overwhelmed. Support groups are key to helping.

Hoarding is very complex, and its triggers are diverse and usually sit alongside other mental health issues. Trauma, depression, brain injury, PTSD and loss are some of the major contributors. Cognitive behavioural therapy, emotional freedom technique, mindfulness, counselling, brainspotting, eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy and compassion-focused therapy are a few of the treatments that can help.

It takes a range of approaches to help people to achieve a mindset where the desire to clear overcomes the need to keep. Motivation and mindset can be key to long-lasting success.

There has been wider progress in holding the first national hoarding conference this year, along with the annual hoarding awareness week each May – in October there is an international hoarding conference being held in Edinburgh. As well as making individual progress, each case contributes to much-needed research into a condition that is still being understood.

Our work with hoarding is a vocation, and I am privileged to work with individuals in their homes, learn about their lives, understand their triggers and hear their voices.

• Jo Cooke is director of Hoarding Disorders UK and author of Understanding Hoarding

Yahoo News

Yahoo News