Professor Ian Glynn, physiologist who studied the body’s vital ‘sodium pump’ – obituary

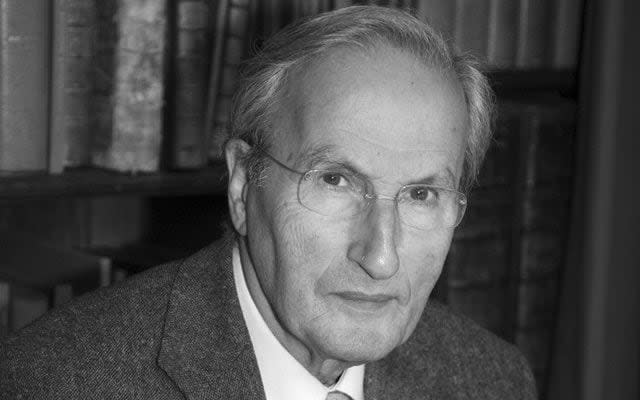

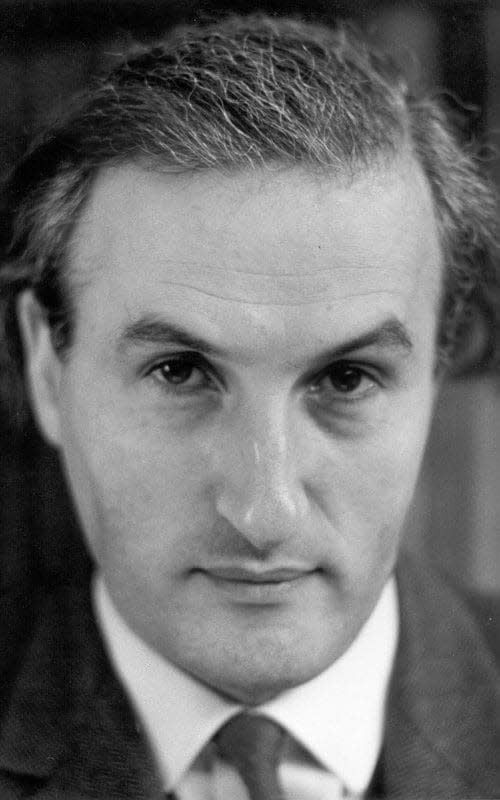

Professor Ian Glynn, who has died aged 94, was a distinguished physiologist with a particular interest in the mind-body issue and an impressive grasp of philosophy, cognitive science, psychology, and evolutionary theory.

A fellow (and vice-master from 1980 to 1986) of Trinity College, Cambridge, Glynn was elected FRS in 1970 for his work on a mechanism called the “sodium pump”, that transports sodium ions across cell membranes, in exchange for potassium ions or other substances. Sodium ions play an important role in many physiological processes, including regulating blood volume and blood pressure and keeping the brain’s batteries charged.

Glynn also wrote books for a general readership, notably An Anatomy of Thought: The Origin and Machinery of the Mind (2000), in which he ranged over such phenomena as emotions, memory, attention, free will, morality and consciousness, relating mind and consciousness to brain cell processing and circuitry.

Along the way, Glynn entertained his readers with quirky facts – for example that the meteorite that fell out of the sky at Murchison, Australia, in 1969 included in its chemical composition a key neurotransmitter in the human brain.

He also recalled the famous case of “Patient HM” who, as a result of a neurosurgical operation could not remember anything for more than a few minutes yet learnt how to navigate complicated paper and pencil mazes, improving his performance impressively even though he could never consciously recall having worked through a maze before.

Ian Michael Glynn was born on June 3 1928 into a Jewish family, the son of Hyman Glynn and Charlotte, nee Fluxbaum, and brought up in Hackney.

Members of his family were medics and he recalled, aged about eight, walking into the kitchen to find an aunt dissecting a human brain. There was a real skeleton in the family closet, which had been studied by three generations of the family.

From the City of London School, Glynn read Medicine at Cambridge, landing in Trinity after failing to impress an interviewer for a scholarship at St Catharine’s who challenged him to identify a stuffed cuckoo. His answer – “It’s... It’s a stuffed bird” – was “not thought worthy of a college scholarship”.

At Trinity, his director of studies was Alan Hodgkin, who subsequently offered him a place as a research student in the Physiology Laboratory. He took it up in 1953 after clinical training at University College Hospital and six months as house physician at the Central Middlesex Hospital, where, during the Great Smog of 1952, there were so many patients with bronchopneumonia that he had to write “Not Bronchopneumonia” in large letters on the notes of other patients.

Back in Cambridge, inspired by the work of Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley on the mechanism of conduction in nerves, Glynn began the research on the “sodium pump” that was to keep him busy for the next 40 years. In 1955 he was elected to a research fellowship at Trinity, and in 1956 completed his PhD.

His progress was interrupted by National Service, which he did in the RAF Medical Branch as medical officer to RAF Sutton Bridge, where servicemen were busily engaged in picking up “bits of crashed aircraft in East Anglia before they demoralised more important parts of the Air Force”.

When Sutton Bridge closed down he spent his remaining National Service helping the surgical team at Papworth, who were trying to establish techniques for open-heart surgery. There, Glynn’s understanding of hydraulics solved problems they had in developing an artificial heart-lung machine for pumping and aerating blood.

Glynn was Professor of Physiology at Cambridge from 1986 to 1995. As well as An Anatomy of Thought he published Elegance in Science: The beauty of simplicity (2010).

In 1958 he married Jenifer Franklin, the sister of the scientist Rosalind Franklin. She survives him with their two daughters and a son.

Ian Glynn, born June 3 1928, died July 7 2022

Yahoo News

Yahoo News