This Icy Moon Orbiting Saturn Is More Alive Than We Thought

When NASA’s Cassini probe visited Enceladus, the sixth moon of Saturn, back in 2005, its observations led to a startling discovery.

The icy moon, 310 miles in diameter, isn’t just another cold rock. It’s active—a veritable chemistry lab in space. A salty ocean sloshes beneath its frigid crust. Vents in the ice, concentrated along the moon’s southern pole, pump powerful chemical plumes hundreds of miles into space.

All that active chemistry bumped Enceladus up to near the top of the list of planets and moons in the solar system that might have the right conditions for simple forms of life. But some key ingredients for microbial evolution seemed to be missing. A major one was hydrogen cyanide, sometimes called prussic acid, which is highly flammable, extremely poisonous but also super-useful here on Earth as a component in many industrial chemicals and pharmaceuticals.

More than 15 years after Cassini reached Enceladus, a team of researchers from Caltech and Harvard took a closer look at reams of data the probe gathered during its 10-year mission, and concluded the initial readings were wrong. Enceladus does have hydrogen cyanide, astrobiologists Jonah Peter and Kevin Hand and planetary scientist Tom Nordheim claimed. And that bodes well for hopes that the icy moon is home to alien life.

Is This Icy Moon Our Best Chance to Find Alien Life?

“Our results indicate the presence of a rich, chemically-diverse environment that could support complex organic synthesis and possibly even the origin of life,” Peter, Hand and Nordheim wrote in a new study, not yet peer-reviewed, that appeared online on Jan. 12. All three scientists are associated with Caltech and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Peter also works for Harvard.

The team’s findings could compel scientists to further prioritize Enceladus as they intensify their search for alien life. It might even become a higher priority than Mars, Venus and even Europa, a moon of Jupiter that has a lot in common with Enceladus and is a favorite target of alien-hunters.

That doesn’t mean first contact is imminent. Right now, what scientists hope to confirm on Enceladus are the clear conditions for life, somewhere under the moon’s chilly crust. Checking all those chemical and environmental boxes could justify new missions to the moon in coming decades.

And it’s those probes that might find very simple forms of life: bacteria or other microbes. “I find the prospects for microbial subsurface life in Enceladus or Europa high,” Avi Loeb, a Harvard physicist who was not involved in the Cassini re-analysis, told The Daily Beast.

Though Loeb did caution: “I doubt that there are dead fish lying on the icy surface.”

Biologists generally agree that simple organisms, as we understand them, require certain ingredients in certain combinations in order to evolve:. carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur and phosphorus, for starters. And there needs to be enough volatility in the surrounding environment—basically, elements moving and churning—to provide the energy for chemical reactions that mix, match and remix these elements until they produce something capable of eating, metabolizing, excreting, breathing, moving, growing, reproducing and responding to external stimulation. That is, life.

There are important middle steps in this evolutionary process. And hydrogen cyanide—a compound of hydrogen, carbon and ammonia with the chemical formula HCN—makes one of those steps possible. “With HCN, you can build biochemically-important molecules such as amino acids,” Dirk Schulze-Makuch, an astronomer at Technical University Berlin, told The Daily Beast. Amino acids in turn can form proteins, which living cells need in order to function and reproduce.

Crunching the data from Cassini’s first pass through Enceladus’ southern plumes, scientists quickly found signs of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and sulfur. The plumes indicated volatility—so among the basic ingredients for life, the moon was only missing a couple things for evolution. Hydrogen cyanide, or something like it, was one of them.

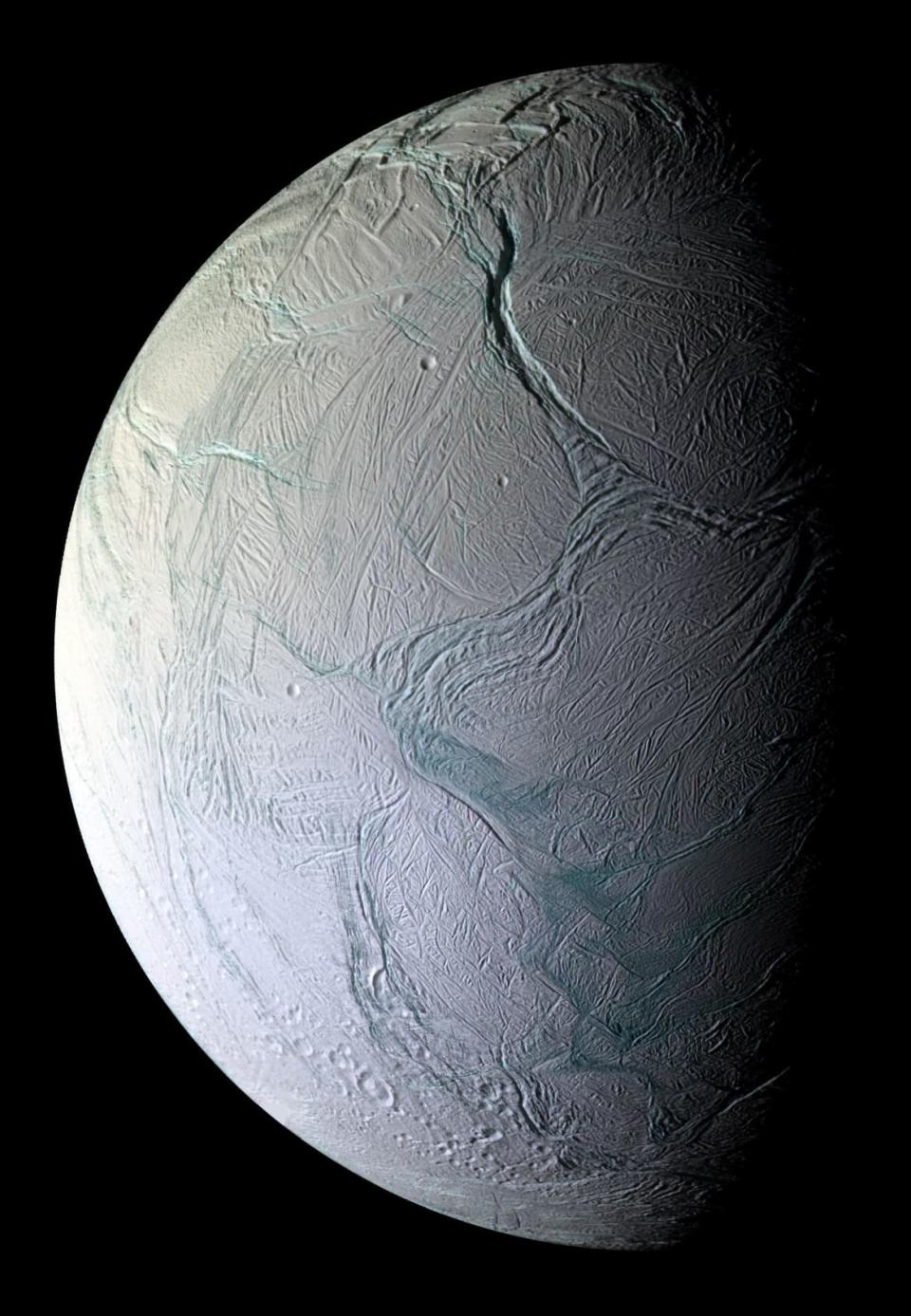

A view of Enceladus captured by NASA's Cassini probe.

But the compound was there all along—scientists just didn’t notice, according to Peter, Hand and Nordheim. “Identification of minor species in the plume remains an ongoing challenge,” they wrote, using the term “species” to refer to types of chemicals.

The problem is that Cassini’s Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer, a device that identifies chemicals by weighing their components, produced raw data that required careful analysis. As our analytical techniques improve, scientists are only now able to tease new discoveries out of old data. That’s exactly what happened when Peter, Hand and Nordheim revisited the Enceladus files. “The authors were able to squeeze out a bit more from the dataset,” Frank Postberg, a planetary scientist at Freie Universität Berlin, told The Daily Beast.

It’s still possible that Peter, Hand and Nordheim’s findings fall apart under peer review, or with follow-up investigation by different teams. And even if they do hold up, we’re still a long way from confirming the conditions for evolution on Enceladus.

What’s Next for NASA’s Cassini Mission Space Explorers?

For one, we’re still missing something. “Phosphorus and sulfur are vital ingredients for life as we know it,” Postberg pointed out. “Phosphorus has not been detected yet on Enceladus—and sulfur, only tentatively.”

It’s possible that signs of phosphorus, and clearer signs of sulfur, are hiding in the old Cassini data, just like hydrogen cyanide was. It’s also possible someone needs to send new and better probes to the moon for more data. “We probably would need a new mission with an instrument… that is tuned toward the detection of large organic molecules,” Schulze-Makuch said.

A mass spectrograph with an added gas chromatograph—a device that burns chemicals in order to analyze them—would be a useful feature on a new Enceladus probe, Schulze-Makuch said.

That hypothetical probe might be able to confirm, in Enceladus’ plumes, the presence—or absence—of the basic ingredients for evolution on the moon itself. A follow-on mission could then go searching for the result of that evolution: tiny organisms living, dying and reproducing in Enceladus’ underground sea.

That would be an expensive undertaking. Cassini cost $3 billion—and that was nearly 20 years ago. Future missions to Enceladus could be even pricier.

Peter, Hand and Nordheim’s work is an argument in favor of the investment. The sixth moon of Saturn is looking better and better as the first place we might find alien life. But a “more detailed examination of Enceladus’ oceanic material,” the trio wrote ”will require future robotic missions.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News