James Cromwell: ‘When you reach a certain age, you have everything taken away from you’

James Cromwell – activist, actor, the voice of reason in Succession and the farmer in Babe – is explaining his love of Britain’s Got Talent. “It’s the best of England,” the 81-year-old says in his velvety, sensitive timbre. He recalls two boys who auditioned with a song about being bullied, and promptly chokes up. “In America, it’s all violence, instead of love, compassion and feeling. What I love about the show is that Simon – ” Cromwell’s voice cracks, and he clears his throat. “Oh, I get emotional. The way Simon Cowell and those judges embrace people who have the courage to come out there…”

He moves on to The X Factor, specifically Cowell tearing up over a young man grieving for his best friend, and “that wonderful woman from the north of England” – Cheryl, I assume. “She’s there asking: ‘How can we ease his pain? How can we celebrate this man? How can we get him through to the next moment but also allow him to have his feelings?’” Cromwell sighs, misty-eyed. “That’s the kind of work I look for.”

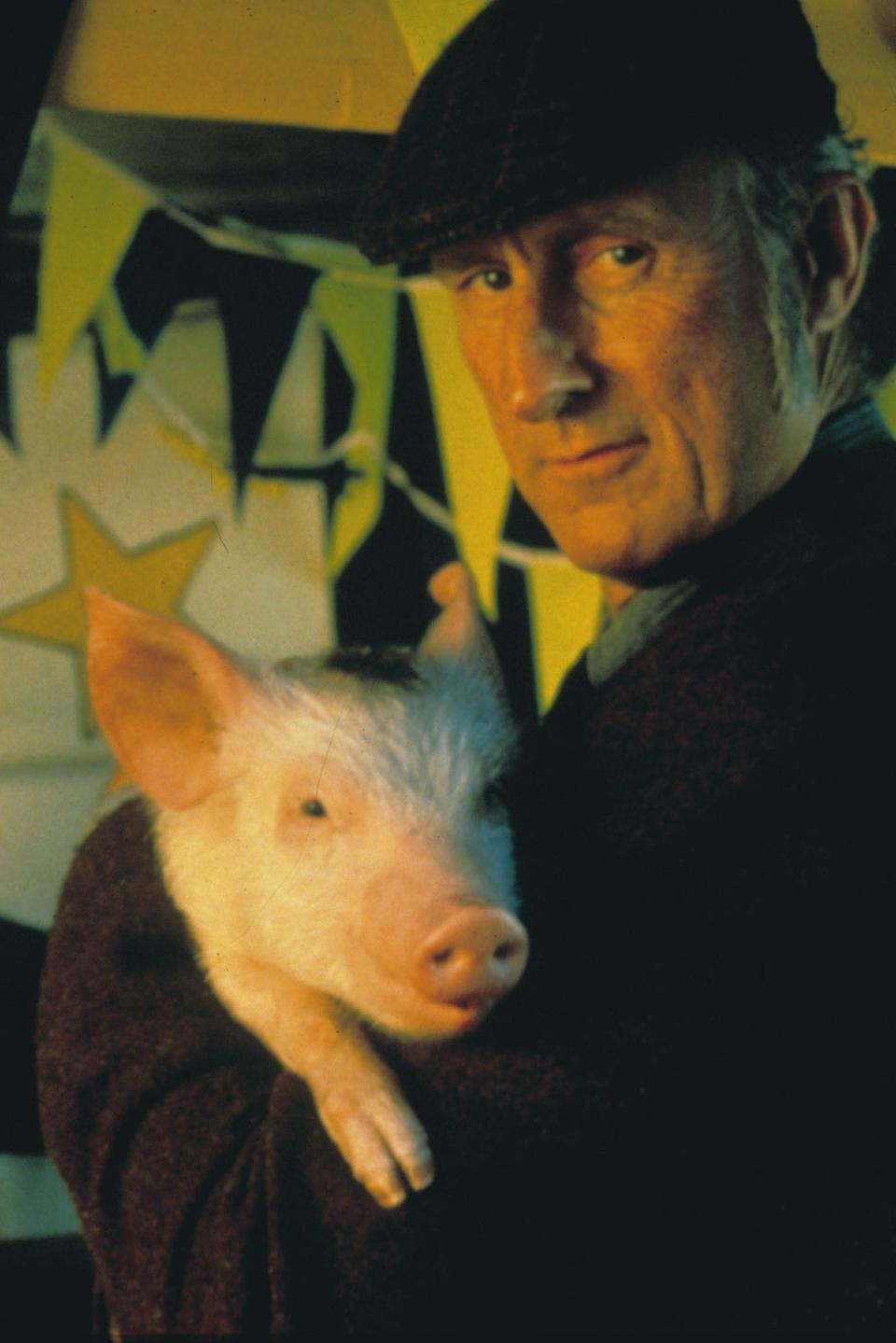

In a conversation that covers everything from politics to pigs to protest, Cromwell’s adoration for weepy British reality shows is a mere aside. But it also gets to the root of him. While he’s played dreadful people before – the corrupt police chief in LA Confidential, a Nazi doctor in American Horror Story: Asylum – he is most often associated with morality, goodness, or gently telling a talking hog, “That’ll do, pig.”

Off camera, whether protesting for animal rights or leading anti-capitalist sit-ins, he is capable only of empathy for society’s most vulnerable. He also sports a kind of eternal youth, an older man still seeing the world through innocent eyes. “To me, I’m 19,” he jokes. “I still make the same 19-year-old mistakes. Hopefully not as many, but just about. Those same dreams and desires still inform everything that I do. And for a funny-looking six-foot-six guy, I haven’t done too badly.”

Cromwell is calling from the log cabin in upstate New York that he shares with his wife, Anna. She owns 13 acres of land, all of which is currently blanketed in winter snow. Cromwell’s brother-in-law lives next door with his family, and performs most of the legwork around the property. “He cuts down the trees and ploughs the meadow, and I just sit here and get fed,” he chuckles.

Cromwell has lived at the property for seven years, having swapped a “postage-stamp”-sized cottage in Los Angeles for large swathes of farmland and forest. “I can’t imagine at my age keeping up with the rhythm of a city,” he says. “After you’ve had a whole life of it, you want to sit back and let life flow over you. I know I’m going down the stream, I know what the end is, so at least let me just sit here and enjoy what I see.”

There is a pragmatism to the way that Cromwell talks about death. He broaches the subject often, unfussily, as if it would be pointless not to acknowledge that it’s nearer than it used to be. But it also feels jarring at times. Cromwell is still visibly passionate about the work he has to do, and his face still bears the twinkly wisdom that made him so endearing in Babe.

His new film, the Australian comedy Never Too Late, exploits such sprightliness. He plays a Vietnam veteran confined to a retirement home in Adelaide, who is far more cogent than the staff insist he is. Recruiting fellow members of the PoW group he fled captivity with decades earlier, he plots to escape the institution and reunite with his lost love – a former combat nurse played by Jacki Weaver.

Weaver and Cromwell have lovely chemistry, with the latter finally getting the chance to play a romantic lead. In 1995, around the time that Babe was released, he told a journalist that he wished he were cast more often as the “lover” in a film, or someone with a rich inner life and sexuality.

“Character actors never get the girl,” he explains today. “Their romantic life is of no interest. You’re there to serve the lead, who gets to express feelings and have relationships. As a human being, I wanted to be able to express a part of me that I don’t get many chances to express.” The closest he came back then, he adds, was with Babe. “I have a relationship in that film, but it’s inter-species. I understand the animal and what its aspirations are. It has courage, which inspires me to have courage.”

Cromwell also liked what Never Too Late says about elderly people – who, he says, regardless of their individual capabilities, tend to be infantilised by society and shut off from the world. “When you reach a certain age, they say, ‘That’s it, you’re finished, don’t drive a car, we don’t want to see you any more.’ You have everything taken away from you, and you don’t exist in the world as a viable entity.” He waves his finger at his camera. “Unless you give something back to yourself. You’re still alive, you’re still learning. You can still contribute, you can still make a difference, you can still inspire. And what else is there?”

Cromwell’s creative life has tended to intersect with his activism, but not always deliberately. Years before he shot to fame and earned an Oscar nomination for Babe, he was a jobbing TV and theatre actor and the son of a filmmaker – Of Human Bondage director John Cromwell, who was blacklisted during the McCarthy era. “I felt like the Woody Allen character Zelig,” he jokes, “always at the periphery of some great event that’s happening, regardless of his own participation.”

He was touring the American South with a theatre troupe at the peak of the Sixties civil rights movement, and then got involved with anti-war activism in the Seventies. His work in guerilla theatre – protest plays often performed in public and without permission from the authorities – saw him cross paths with Black Panthers, anti-capitalists, and those opposing sexism, homophobia, nuclear power and environmental cruelty.

“In other words, I sort of fell into things,” he says modestly. “Those I most respect are the unsung people, who don’t relent and don’t lose their passion. They’re the heroes. I have my issues now – physically – which make a lot of what I used to be able to do unattainable for me.”

He’s still putting in as much work as he can, though. He’s currently under six months’ probation for protesting against animal cruelty in Texas, and was charged with a third-degree misdemeanour in 2019 for protesting against the construction of a natural-gas-fired power plant near his home. “I don’t know whether it’s affected my ability to act,” he says. “Maybe in Hollywood – I think they’d just as soon not have me. But I still work frequently, so that’s good.”

But that work needs to align with his values, he says. When Cromwell was approached by Succession creator Jesse Armstrong to play the older brother of billionaire bastard Logan Roy (Brian Cox) in the series, the actor initially balked at the idea. During an hour-long conversation about the part, he encouraged Armstrong to rework the character into having more of a moral compass than just another Succession monster.

“The entire world of the show is dark and bereft of any kind of community,” he explains. “Each action is covert and every character has an agenda, and you must defend yourself against people like that. That’s what I feel about the class of people represented in Succession, and the class of people that seem to be running this country and running it into the ground.” He didn’t believe that a Vietnam vet like Ewan Roy would have emerged from war without compassion for his fellow man, and insisted that his character reject the selfishness and moral debasement that Logan embraces. “Bless their hearts, they gave me a wonderful character to play. I love Jesse for that. Because we must speak truth to power – that’s where change comes from.”

I admit that – in our current climate – it’s hard to not feel as if progressive politics are a doomed endeavour. How does he maintain hope? “We can’t be disheartened,” he says. “We can’t afford to be. The best way to deal with what you’re feeling is to become engaged. True journalism is incredibly important now. Telling the truth is really important now. You know King Lear?” He stretches out his arms and grips his Zoom camera between his hands: a private one-man show. “‘The superfluous and lust-dieted man that slaves your ordinance, will not see because he doth not feel… So distribution should undo excess and each man have enough.’ – It’s right there! He said it. God’s gift to the world: William Shakespeare.”

With that dramatic call for the redistribution of wealth, Cromwell pledges to keep fighting. “Laws against legitimate, constitutionally guaranteed protests in this country are becoming more and more prevalent, and they are doing it not to stifle the right but the radical left,” he says. “I can’t say I’m a revolutionary because that would mean total commitment. But I’m on the cusp, and my time will come when my voice is required again and my presence will make a difference.” Before we say goodbye, he delivers one last soliloquy down the camera lens – the consummate performer. “Do not go gentle into that good night,” he bellows. “We must rage against the dying of the light!”

‘Never Too Late’ is in cinemas from 4 February

Yahoo News

Yahoo News