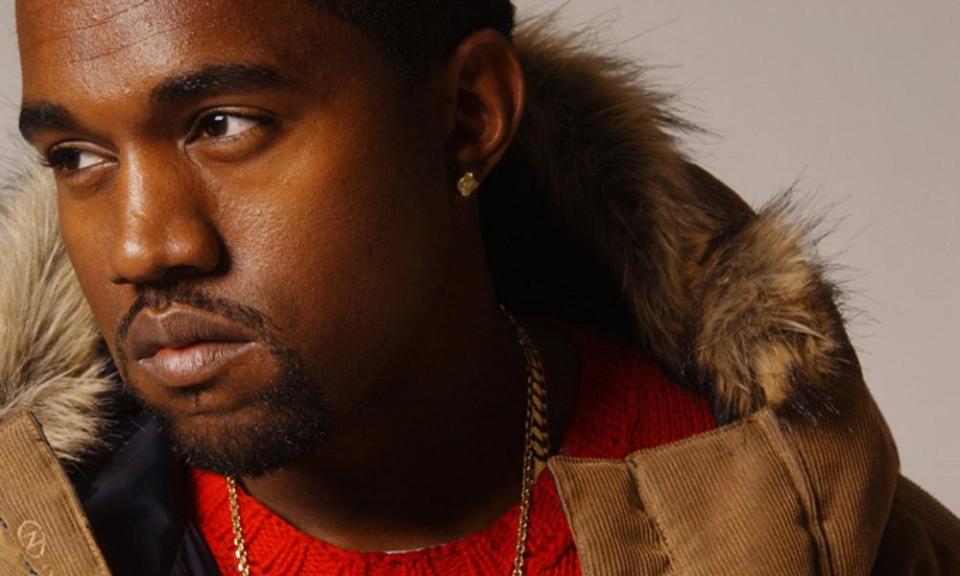

jeen-yuhs: what can we learn from the new Kanye West documentary?

Much like Jesus Christ, the friction between Kanye West and the general public comes from an attunement to the grandeur of his own destiny that can read like delusional arrogance. His first album as a rapper, 2004’s The College Dropout, is littered with nods to his significant place in history and how they foretell an auspicious future. He mentions his mother’s arrest at “the tender age of six” for Oklahoma City’s sit-in protests, declaring “with that in my blood, I was born to be different”. As he’d have it, it was no mere coincidence that on the fateful night of his near-death experience in a 2002 car crash, he was brought to the same hospital where Notorious BIG drew his final breaths. In one of the comedic skits breaking up the tracklist, a snot-nosed character delivers a line that rings out like a broad artistic statement of purpose for its writer: “This was meant to be.”

Related: Kanye West wants to approve final edit of Netflix documentary Jeen-Yuhs

And indeed, it was. Many of the claims that skeptics took as boastful chest-puffing – that he’d be one of the greatest emcees to ever pick up a mic, that he’d revolutionize hip-hop and fashion in his own image, that he would attain such notability as to make him one of the main characters of planet Earth – were borne out with time and recast as extreme yet correct self-assurance in the face of insecurity. (Crucially, The College Dropout is also shot through with feelings of inadequacy, West’s anxiety about living up to the stratospheric standards he feels God has set for him.) Though his belief in himself may have been expressed in the language of borderline-pathological ego, his later successes retroactively transformed that mentality into a defiant assertion of worth. The future’s context brings clarity to the past deeds and words of a confounding, complex figure, but in the new documentary jeen-yuhs, that cuts both ways to shed some insight on the chaos that’s engulfed West as of late.

The three-part bio-epic from music video stalwarts Coodie and Chike, now playing through the virtual Sundance festival prior to a Netflix debut in February, tracks West’s trajectory from an intimate on-the-ground perspective with the breadth of a bird’s-eye view. In covering 21 eventful years in the life of the enigma now known as Ye, with special focus placed on his formative pre-fame era, we can start to make sense of the erratic later period that’s seen West palling around with Trump, getting born again, and wilding out (even for him) on social media. Coodie and Chike’s diligent portraiture teaches any given viewer what armchair celeb scholars already know: with enough close study, even the most bewildering famous-person behavior can be rendered comprehensible. The recent name-change, for one – when a young West saw himself erroneously billed under the mononym of Kanye, he joked to Coodie that he’ll preclude disrespects moving forward by ditching his surname, or better yet, just going by Ye.

The four and a half hours of jeen-yuhs yield a handful of prophetic moments like this, in which happenings decades down the road are foreshadowed with eerily specific prescience. In one of the dozens of cameos sure to please devotees of early-aughts hip-hop, Pharrell Williams stops by the studio as West prepares his sophomore LP to lay out the younger man’s next chapter. West will make it, Williams soothsays, and when he does, the greatest threat to his brilliance will be a complacency he can only stave off through constant hunger and self-doubt. With these words in mind, the shape-shifting that would define his career after he earned GOAT-level plaudits for My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy in 2010 starts to resemble a master’s search for a new challenge, rather than a haphazard effort to see what works. Alexander wept, for there were no more rappers to conquer, so he made an indie rock album with Kid Cudi and then went gospel.

More often, however, the connecting lines aren’t so direct. The structure of the film’s three sections (the first starts in 1999 and ends with West signing to Roc-A-Fella Records in 2001, the second makes it to his double-win at the 2005 Grammys, and the third blazes through the next 16 years) invites us to form an impression of West’s personality and then use it as a decoder. His meticulousness as a musical technician plays against a natural sense of humor in his come-up, a big grin and unchecked laugh gone from the final third aside from the briefest flicker. In his loping, endearing voiceover narration, Coodie states in plain terms that some inner glow seems to have faded from West in the time since they last met.

We see that his shoulder is all chip, a complex he’ll spend the rest of his adulthood raging against. As a Black man in a racist country, as a preternaturally gifted producer no industry gatekeepers wanted to hear rhyme, and as a Chicagoan in a rap topography with peaks in Los Angeles and New York, he came to the game in a defensive crouch he never really left. Coodie and Chike emphasize the tooth-and-nail fight for every scrap of recognition; in a scene both funny and sad, West barges into offices at Roc’s headquarters and spits verses at a series of mid-level executives until he can find whoever will give him a deal. Having to take everything he’s ever been given permanently sculpted West’s psychology, making him an underdog surrounded by influential people who want to see him fail. West would later claim to relate to Donald Trump through their shared “dragon energy”, an inscrutable euphemism for the sheer might required for an outsider to bust into a power structure pitted against him.

Every bit as telling is his relationship to his mother Donda, the only person more important to Kanye West than Kanye West. Beyond singlehandedly raising her son in the wake of a divorce when he was only three, she’s supplied him with the unflagging, unambiguous encouragement he needs in his uphill pursuits. In one poignant scene at his mother’s apartment, West does an a cappella rendition of his devotion song Hey Mama for her, both smiling as he recalls her supporting his choice to bail on higher education despite disagreeing with it. He transforms around her, loosening into a happier, more relaxed version of himself. Her death in 2007 precipitates West losing the levity that animated his first three albums, and along with it, his sense of what matters to him. (It’s hard to discern the place family has in his life once he starts his own, as ex-wife Kim Kardashian is conspicuously absent in the film, surely due to some legal jiu-jitsu behind the scenes.)

However sympathetic to its subject, the film isn’t flattering in its attempts at understanding. The notorious clip of Barack Obama referring to West as a ‘jackass’ goes hand in hand with an embarrassing encounter in which West drunkenly refers to Coodie by the wrong name following a while apart. At one point, West mentions his difficulties with medication and drug use in passing. A few days ago, he took to Instagram to demand final-cut privileges over Jeen-yuhs so that he can “be in charge of [his] own image.” But Coodie and Chike haven’t set out to get him, nor absolve him. They come from a place of genuine concern, helpless to watch a man with a turbulent brain losing his way, hoping only that he can find the aid he needs.

At the heart of their before-and-after technique is uncertainty over the elusive question of the “real” Kanye. The directors leave us to ponder whether he’s a decent soul who’s gone astray or a megalomaniac who’s achieved his true form, each conclusion negating the other. Their film is a prism, refracting the image West is now fighting to control, its picture depending on the angle from which we view it. Early on, we see him lay down a verse from College Dropout cut Never Let Me Down, saying that his fellow Black voters “can’t make it to ballots to choose leadership / But we can make it to Jacob’s and to the dealership”. At the time, it sounded like a callout to injustices stripping minorities of their political rights while they’re distracted by material riches. But in light of his outrageous third-act comments that slaves made the choice to remain in bondage for 400 years, that line takes on the tang of blame, as if he’s chastising the African-American community for their own disenfranchisement. We can’t know which parts of Kanye West are sincere and which are a troubled distortion of the same. His past and present are inextricable, both in a state of continuous reassessment. All we can do is observe how they feed into and warp each other.

jeen-yuhs is showing at the Sundance film festival and will be available on Netflix in February

Yahoo News

Yahoo News