JW Anderson: ‘We’re too scared to be controversial now, someone like McQueen could not exist today’

“When it comes to culture — fashion culture, art culture — we are in this incredibly insane moment of self censorship,” says 38-year-old fashion designer Jonathan Anderson. “I think we are too scared to have dialogue, too scared to be controversial — because we’re worried that we’ll be cancelled. And it makes me feel that, creatively, everything is moving incredibly slowly.”

It’s perhaps a sign of the pace that Anderson moves at — a world most of us find overwhelmingly fast, he finds stultifying. Born in Northern Ireland (he’s lived in London for more than two decades), he heads up two of the world’s coolest fashion labels: the eponymous JW Anderson, which he launched aged 24 in 2008 as a menswear label (he added womenswear in 2010), and Spanish luxury juggernaut Loewe, which under his decade-long stewardship has become a $1 billion-a-year brand. He creates 18 collections each year — six for JW Anderson, 10 for Loewe and two as part of a collaboration with Uniqlo.

And alongside the fashion, there’s the art, which I get the sense is his first love. He’s a prolific collector; his east London house is “a complete cluster mistake because I can never decide where everything goes — I kind of get bored of things”. At the moment he’s “trying to rediscover an idea of minimalism — I stripped everything out of the house recently, when I get back from Paris it should hopefully be as empty as possible. I’m painting it a different type of white to try to find a different type of energy.”

We are meeting to talk about a new art exhibition that he has curated, the second he’s worked on (after 2017’s well-received Disobedient Bodies, at The Hepworth Wakefield). It’s a labour of love, he tells me, showing me into the Offer Waterman gallery, just off Hanover Square. On Foot is an homage to London and brings “contemporary artists into dialogue with iconic works of modern British art”.

I live between London and Paris, and the anxiety of Brexit — and now the reality of it — made me go through this period of feeling quite down about the UK

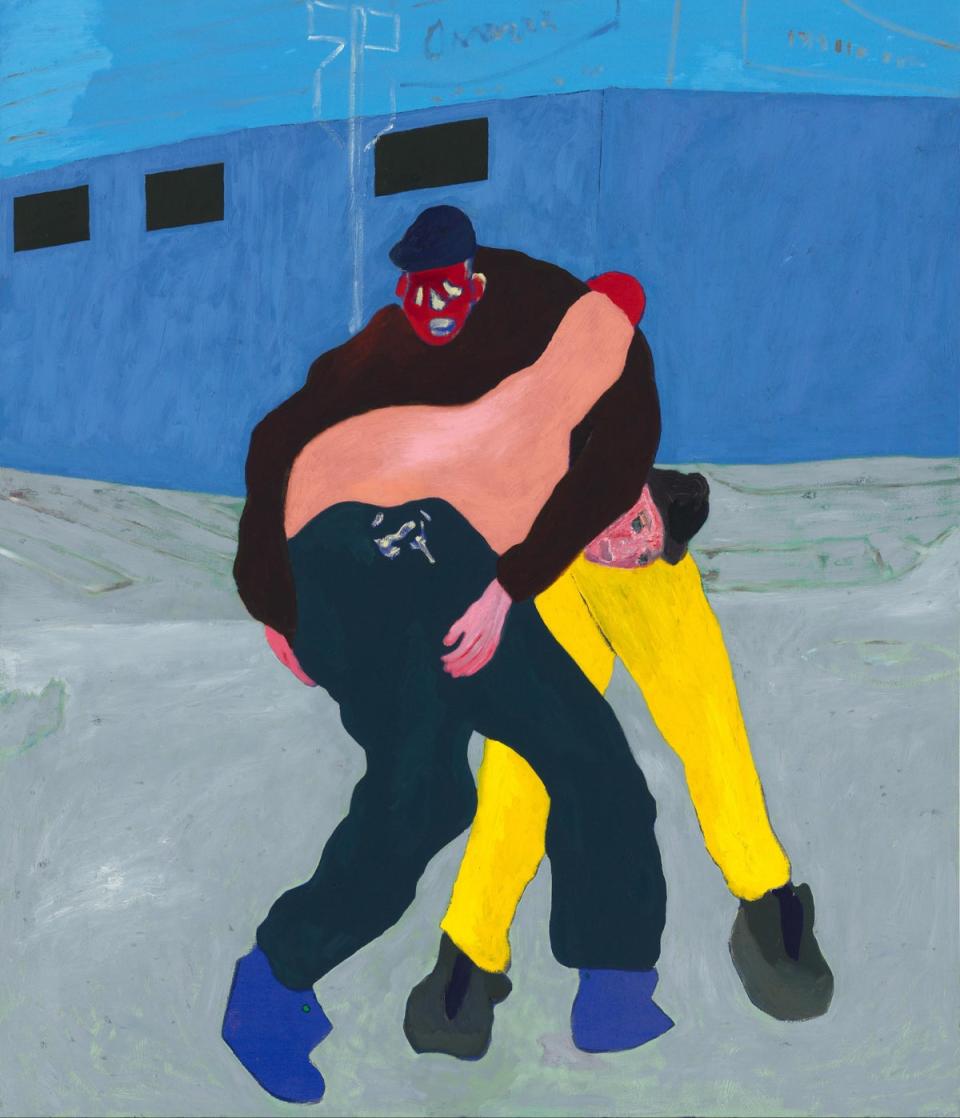

Ahead of our interview I am told that his diary is generally blocked out into 10-minute time slots and I’d expected to find him a little flustered. It being just a few days before his SS24 show at London Fashion Week. If he’s feeling at all overwhelmed though, he doesn’t let it show. He is generous with his time, lingering over the artworks, pointing out specific details, explaining why he selected two particular artists to be displayed together, what he loves about LS Lowry (who is part of the exhibition) and how that relates to the work of contemporary painter Florian Krewer (also in the exhibition): “with the faces, Lowry kind of cuts down into the paint, so you get this idea of relief. You look at Krewer and he does a similar kind of thing, he cuts back into the oil… ”

When I ask how he’s feeling about Saturday’s show, he smiles, “I’m looking forward to it. It’s going be a fun show. We’ve done a very tight edit. I always find these shows very cerebral somehow, it’s sort of like the warm up for the entire year.” All very chilled.

The gallery is in a five-storey Georgian townhouse that once belonged to William Morris and each room of the exhibition is meant to feel like you’re dropping in on a different London scene — a street, a skate park, a pub. “I live between London and Paris, and the anxiety of Brexit — and now the reality of it — made me go through this period of feeling quite down about the UK,” says Anderson as he walks me through the various rooms. “But this is a show that is really meant to kind of glorify London, and how much it gives us.”

We are trapped in a never ending cycle of ‘Like’ culture

This is how we get onto the issue of censorship — because while London gives a lot, it’s also a difficult, expensive place to be a young creative. Does he worry that it risks losing its place as a home of disruptive culture if future generations simply cannot afford to live or work here? “I actually don’t think it comes down to economics,” he says. “I think the problem now is that we are our phones. We are trapped in a never ending cycle of ‘Like’ culture.” Young creatives, he points out, “want things quickly, want to be famous quickly — the idea of doing the long mile is not really happening anymore…there’s this attitude like, ‘I have a phone so then bam, I can start my thing, and that’s it.’ But in fashion, and in art, I think you have to kind of go through the failures to get to somewhere significant. And I think in a weird way, we’ve built a society where we cannot fail, because we’ve cancelled anyone who does.”

Anderson, I quickly realise, is a purist when it comes to art. He wants it to be challenging, painful even. He hates the idea of playing it safe. “All of culture is too safe now,” he tells me, at one point. “You can’t have a conversation, or say what you feel without having to navigate this weird safety culture. And it is impacting creativity; you know, people like Rembrandt could not exist today, McQueen could not exist today. Yes, things have to change. But I think we should still be trying to work out how we challenge people in art, in theatre, in music.” As a designer, he’s often been praised for creating challenging clothes; deconstructing and reimagining garments, drawing references from across the vast spectrum of art and culture — and it has kept him at the forefront of the conversation for well over a decade, and made both JW Anderson and Loewe incredibly lucrative brands.

You can’t have a conversation, or say what you feel without having to navigate this weird safety culture. And it is impacting creativity

It surprises me that, given that level of success and what seems to be a fairly freewheeling creative output, Anderson feels stymied. Is there anything in particular he’d like to say that he feels he can’t? It’s more an atmosphere, he demurs. He looks back fondly, for instance, on the 2013 menswear collection that saw him branded a menace to fashion for showing gender fluid looks. “At JW Anderson the humiliation of the models was made truly complete, as the designer sent out his clan of put-upon male beauties wearing frilly shorts, leather dresses and frill-trimmed knee-length boots,” wrote one reviewer. “I was cancelled, technically,” says Anderson. “And like, whatever it felt normal to me at the time…like, so what if people hated it? In a weird way, what I quite liked about that period was that, at least there was a point of view. At least people could hate something. Now we don’t hate anything, or only on the far outskirts of the internet. Now it’s all self-censorship.”

Anderson has talked in the past about growing-up in the midst of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. As he once described it: “I remember when they blew up Magherafelt [the town he grew up in] high street, and driving past it every day when travelling to school. I remember a sports shop being blown off the face of the earth.” And clearly, being reminded of one’s own mortality on a daily basis has cemented a sense of urgency in him. It’s almost like, knowing how short life can be, he can’t bear things that are insipid or too safe.

His father was a famous rugby player and his mother was a school teacher — and Anderson initially left home aged 18 and moved to the United States in a bid to become an actor. He mainly partied, the period coincided with him coming out as gay. It wasn’t until a few years later that he decided he’d go into fashion — and ended up studying menswear design at London College of Fashion. He doesn’t necessarily rate his fashion education — as he tells me at one point, “I don’t think you can train for fashion, even though people believe you can. I think it happens in the field. Like, as a doctor, I think you have to train in the field to understand how the body works, and you need an education to be able to do that. But within fashion, you don’t need the education to be able to do it. I think you have to have intuition and curiosity, ultimately.”

His curiosity is mainly piqued by art, clearly. My favourite room in the exhibition is the ‘pub’, where a series of portraits by modern and contemporary artists are arranged ‘in the round’ so it feels like you are being stared at from every angle. Anderson’s favourite work in the exhibition is here too: a self portrait of Christopher Wood. Wood is one of his favourite artists, he tells me, “as much for the actual story of his life, as for his painting”. Wood was in fact an enfant terrible of the Twenties Paris art scene, friends with Picasso and Jean Cocteau. He once wrote that he would “try and be the greatest painter that has ever lived”, but then tragically died by suicide aged 29. The painting in the exhibition is mesmerising and has a certain sadness to it. “He was a pure artist,” says Anderson.

I don’t think you can train for fashion, even though people believe you can

As for fashion, Anderson is cautiously optimistic. On a practical level, operating in this post-Brexit climate has been difficult: “Running a business in Britain, in fashion, is quite complicated now — you’re importing in fabric. Then exporting it out again — and there’s so much red tape. For small businesses… and for young designers it must be impossible.” And from an ideological standpoint, he thinks “London has gone through a very odd transition within fashion. I don’t think it’s in its heyday. I think it’s just starting to find its legs again.” What he wants is for us to “gain some self confidence again. We need to be able to say why British fashion is important enough to remain on the global map. Because what would be terrifying to me is that London became a Fashion Week that meant nothing. That would be my biggest fear. Britain has such incredible talent… but I think London is still finding its feet, after Brexit, after the pandemic. Like where do we go? That’s going to take the work of smart minds. I don’t think the answers come from TikTok or from Instagram. I think this is about dialogues and conversations and reflection, ultimately.”

On Foot will be open to the public from 18 September to 28 October 2023; Offer Waterman Gallery, 17 St George St, W1S 1FJ; waterman.co.uk

Yahoo News

Yahoo News