A Killer Canadian Vacation Starts With This Prison Tour

It’s a classic Canadian start to a tour of the maximum-security federal prison that once held our most notorious criminals—we politely sing “Happy Birthday” to a stranger. “I don’t know why your family brought you to prison for your birthday,” tour guide Amy Zurrer teases Colleen Smith, “but we’ll make it very special.”

Don’t translate “special” as “lurid.” These tour guides take the privacy act seriously, so can’t legally dish dirt on famous criminals without permission. Yes, the late serial child killer Clifford Olson, the “Beast of British Columbia” did time here, but our guide will only quietly confirm that he was an inmate. We will not speak of serial killer/serial rapist Paul Bernardo, who committed his sickening crimes with his then wife Karla Homolka. We are not to ask about the more recent serial killer Russell Williams, the former colonel of CFB Trenton, Canada’s largest air force base.

Our guide placates us with promises that we will hear about one of the prison’s most colorful cons, but only because we have permission from his family and because he illustrates an important story. “This is a historical tour,” Zurrer stresses. “We will honor the victims and the families and not make a celebration out of a horrible crime.”

Well, then, let’s get started and learn what we can from Canada’s only federal prison tour, and its oldest and most notorious prison, three hours east of Toronto and taking up prime real estate on the shore of Lake Ontario in Kingston.

You know that saying “If these walls could talk?” Well here they do. The visitation room has a freaky juggler and Mickey and Minnie Mouse striking retro rap poses painted on the wall beside a sign declaring this is a children’s play corner where adults are prohibited unless supervising their kids, and where the television must be turned off if no kids are around. There’s an all-caps memo still on the wall from when the prison was active: “Please do not interact with other people’s children without their consent. Thank you.”

There’s that famous Canadian politeness, again.

America has well-oiled prison tours to places like Alcatraz and Yuma. Crumlin Road Gaol in Belfast does multiple daily tours as well as weddings and “jailhouse rock” shows and even has a restaurant called Cuffs Bar & Grill. Canada, by comparison, mainly has an assortment of under-the-radar penal history museums in decommissioned jails and lockups. (Canadians go to federal prisons for serious crimes, and sentences of more than two years, and provincial jails for less serious crimes and shorter sentences.)

This tour, its first major foray into dark tourism, is about to launch its fourth season and is still anything but slick. Tours are run as a partnership of the City of Kingston, Correctional Service of Canada and the St. Lawrence Parks Commission, which delivers earnest tours through student guides and retired corrections staff like Pat Boudreau who says: “It’s an honor to come back and show her off.”

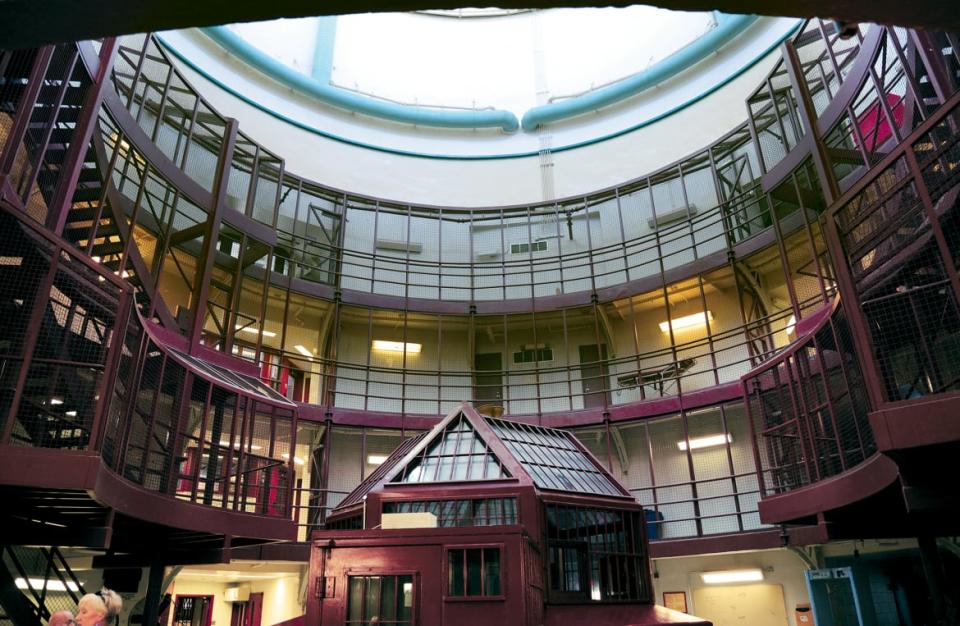

“Her” is “KP,” also known as Kingston Pen. Convicts built her from limestone they quarried and cut, and she opened in 1835, more than three decades before Canada became a country. Author Charles Dickens visited in 1842 and called her “an admirable jail… intelligently and humanely run” in American Notes for General Circulation. A young Ernest Hemingway, working as a reporter for a Toronto newspaper, covered a jailbreak here in 1923.

The prison once housed women and children, not just men, and inspired Canadian author Margaret Atwood to write Alias Grace. It was declared a National Historic Site in 1990 but was closed by the government in 2013 because of aging infrastructure, and her final 441 inmates were shipped elsewhere. KP was decommissioned to save the government money, stripped of anything that could be reused in another institution (excluding an X-ray machine that can’t legally be resold), and then left as is.

This means you will see original graffiti—everything from “Fuck all” and “Mueler is a bird. Scams his own freind (sic). Don’t trust him,” to a haiku of sorts: “Hell’s going with you. Write it on your back. All this will fade to black.”

In a cell block once known as G-Range, retired guard Vern Thibedeau talks about how inmates here “were the bottom of the totem pole” — pedophiles, child killers, informants and even ex-policemen who couldn’t survive in other prisons.

“The writing on the walls and in the cells, anything on the walls, that’s all by inmates. We didn’t run around adding anything since 2013. Well, we did cover up a few things that were overly graphic.”

If an inmate left personal stuff behind, like a sexy poster of actress Parker Posey, a clock radio, Star Wars books and a puzzle in progress, you can view it through the bars. Okay, probably, they compiled a bunch of stuff that was left behind and recreated one cell.

Thibedeau urges me to spend a few moments in an empty cell—which should give me the chills and is definitely sobering, but also makes me feel fairly foolish—and sends me off with the business card that details his memoir called The Door: My Twenty Six-Years Working Inside Canada’s Prison. It was not condoned by his bosses and detailed things like being taken hostage and suffering from extreme stress. It ruffled a few feathers so is not for sale in the tour gift shop, but you can buy it online.

What Thibedeau and the other retirees want people to know is that Canadian prisons aren’t like in the books or movies—with the possible exception of the room where visitors could talk to cons on phones, safely separated by glass.

Federal inmates eat in their cells, not dining halls, and smoking was banned years ago. Inmates here wore jeans and blue golf shirts (without names or numbers), not orange jumpsuits. Family visitation units with small yards—funded by inmates, not taxpayers—allowed some cons to host relatives for 72 hours. An indigenous sweat lodge did allow inmates to use tobacco for sacred rituals. Cells got bigger over the years.

Zurrer tells tales of riots, hostage takings, killings and the occasional escape. Soldiers were called in to quell a 1954 riot. During a four-day riot in 1971, six correctional officers taken hostage and two inmates killed by other inmates. Escapes weren’t common but the late bank robber Ty Conn duped guards in 1999 with a dummy in his bed and is to thank for the rule that inmates must stand up and be counted. He got over the prison fence and escaped for two weeks until he accidentally shot himself in a standoff with police in Toronto.

We hear about free high school courses and flip through an old Business Mathematics in Canada textbook. We tour workshops where cons once learned upholstery, carpentry, furniture making, welding and plumbing and made things that could only be sold to government agencies and not-for-profits—like mail bags for Canada Post.

The biggest revelation: Cons made my high-school lockers.

The biggest success story: One retired guard still gets his hair cut by a former inmate who learned to be a barber here and went on to raise a family and stay out of trouble.

If this is too tame for you, duck across the road to Canada’s Penitentiary Museum, housed in the first official warden’s residence for Kingston Pen and built by inmate labor in 1873. Its contraband room shows off a pile of shanks, makeshift guns, home-brew gear and a hollowed stack of food trays that one clever inmate hid in to escape.

Canada abolished corporal punishment in 1972, but the museum declares: “Only by analyzing where we have been can we intelligently consider what we should do with the future.” Its corporal punishment room has straps and a strapping bench, a rack-like whipping post known as “the Triangle,” a straightjacket and a coffin-shaped box used at Kingston Pen more than 800 times between 1847 and 1849 for anywhere from 15 minutes to nine hours at a time.

Looking around the museum makes me think of Justin Piché, the associate professor of criminology at the University of Ottawa, who has spoken out about this tour and about penal tourism in general. He wants people to think critically about the commodification of punishment. He wishes captives—not just captors—could be humanized on tours and maybe even some who’ve done their time could be hired to be part of tours. He wants prison tours like this one to at least touch on the limits of, and problems with, incarceration. My tour does show how cells have gotten larger, and how corporal punishment rules softened over the years, but as a historical tour it doesn’t delve into controversial issues like prison labor, solitary confinement and the way that black and indigenous Canadians are over-represented behind bars.

Unlike similar tours around the world, Kingston’s prison tours only run from late spring to late summer, partly as the buildings aren’t heated in winter. “It’s not for everyone, certainly,” says my student guide. Tours attracted 59,000 people in 2016 and 105,000 in 2017 before scaling back in 2018 to find a “sweet spot” around 68,000. Tickets are now on sale for this season, which runs May 8 to Sept. 1.

“Like all great tours, you are going to be exiting through the gift shop,” Zurrer tells us as a farewell, hastening to add that sales help support the United Way and homeless youth initiatives. The shelves are pretty bare during my end-of-season tour and there are just a few tastefully branded souvenirs, so you’re better off dashing across the street to the penitentiary museum’s more extensive shop if it’s novelty handcuffs and handcuff-themed jewelry that you’re after.

As for our birthday girl, Smith lives near another federal prison and has a relative who trained drug-sniffing dogs that once worked at Kingston Pen, so she comes by her fascination with incarceration honestly. She tells me she definitely wants the historic limestone prison that once housed Canada’s worst criminals to keep running tours here on this coveted lakefront spot: “I would hate to see it become condos.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News