Kraftwerk 3-D at the Royal Albert Hall, London: Reconfiguring what a pop gig can be - and how it can look

It is hard to conflate the reverence with which groundbreaking German electronic group Kraftwerk are held today with the reception they received when they first arrived in the UK in 1975.

In the excessive age of glam and prog rock, Kraftwerk turned up to play half-full venues looking like investment bankers, creating alien music without a guitar in sight. Misunderstood, they were laughed out of town. “For God's sake, keep the robots out of music” was Melody Maker’s hot take.

Fast-forward to the 21st century and this is Kraftwerk’s world. Everyone else just lives in it. The sound that had so confounded critics and audiences alike - an austere, synthetic meeting of man and machine - is now the basis upon which the last 40 years of popular music has evolved.

Any genre you care to mention - techno, hip hop, dubstep - owes a debt to the Dusseldorf visionaries. Long before the internet, their view on how technology would affect everyday life - the relentless rise of interconnectivity (“Computer World”), the way single people would use digital means to find, if not companionship, “a rendezvous” (“Computer Love”) - was so prophetic as to be scary. That many of these songs were rich with melody only added to their genius.

So Kraftwerk are arguably, perhaps even more than The Beatles, the most influential band of all time. But what to do when the future you so presciently predicted is here? Kraftwerk are of heritage act age in danger of becoming just that. Of the band’s classic line up, only founding member Ralf Hütter remains.

There has been just one album of new material - 2003’s Tour de France - since 1986’s uneven Techno Pop, the moment at which Kraftwerk’s reputation for sonic invention began to recede.

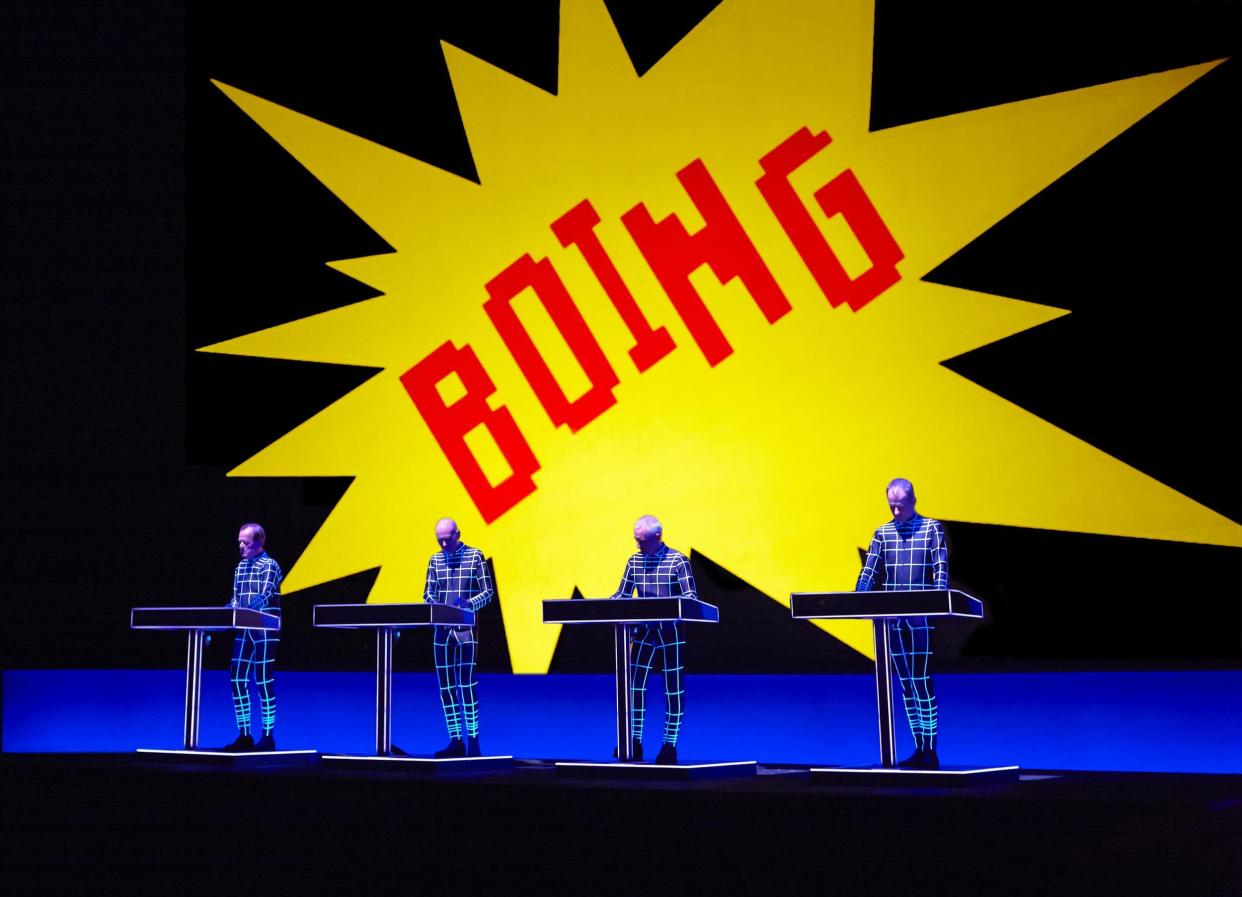

In lieu of new music, Hütter’s answer has been to reconfigure what a pop concert can be; or more accurately how it can look, presenting a reimagining of Kraftwerk’s’ classic catalogue with the aid of retro-futuristic 3D visuals. It is a breathtaking exhibition: music performance as installation art.

The audience watch through 3-D glasses as four men line up in neon bodysuits stood motionless at brightly lit workstations. Aside from Hütter’s occasional vocals, what they actually do there is anyone’s guess - when they are replaced by life-size robot versions of themselves in the encore the difference is negligible.

The spectacle is happening behind them. Within seconds of the opener, 1981’s “Numbers”, we are under siege from a barrage of flying 1’s, 2’s and 3’s; for 1974’s “Autobahn”, the motoric homage to the Beach Boys, we are driven along oddly melancholic empty roads; on “Spacelab” from 1978 we are taken into orbit before the shuttle lands at its destination: just outside the Albert Hall (to much amusement).

Yet rather than adding to Kraftwerk’s otherness, the visuals accentuate the humanity of the music. “Neon Lights”, from 1978, is a gorgeous ode to the city after dark which, with its accompanying dream-like sequence of late-night bars and beautifully lit streets, carries a naive nostalgia. 1975’s “Radioactivity” might have been given a techno makeover, but it is also now an emotive tribute to the victims of nuclear power disasters the world over.

In fact much of the music, while no less precise, is nonetheless overhauled from its ascetic recordings. Nobody dances, but some of this is club music: 1981’s “It’s More Fun to Compute” is propelled forward with a thumping beat; 1978’s “The Robots” comes to life with a dynamic acid house line.

The exception is their 1982 number one “The Model”, played as faithfully as the day it was written because it cannot imaginably be enhanced: proof that at their essence Kraftwerk always were a pop group, and one that for years managed to stay two steps ahead of the rest.

With Kraftwerk 3-D, everyone else is once again playing catch up.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News