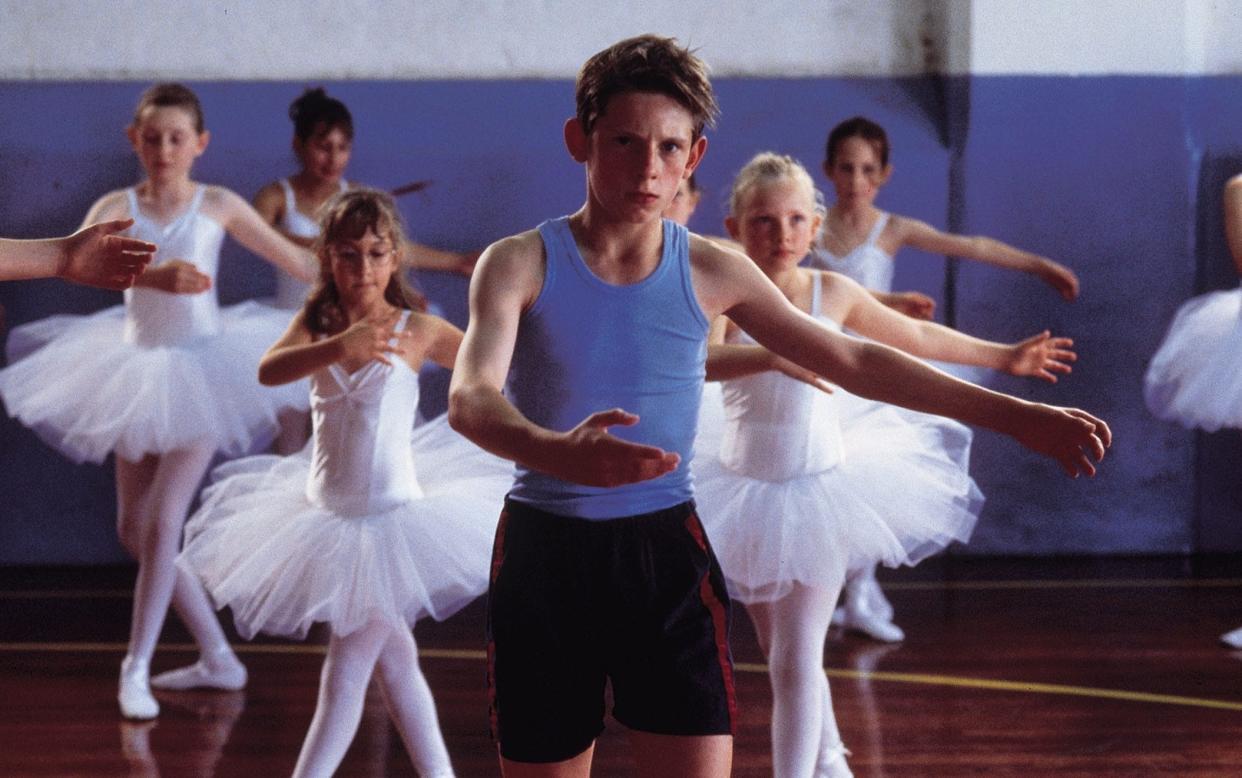

Labour’s tax raid on private schools could mean no more Billy Elliots

The Billy Elliot story could become impossible due to Labour’s plan to impose VAT on private schools, the head of the Royal Ballet School has warned.

David Gajadharsingh said the proposed 20 per cent tax was likely to “destroy opportunity” for talented children from less well-off backgrounds and could end up harming the reputation of ballet in the UK.

In an interview with The Telegraph, he called on Sir Keir Starmer to reconsider the effects on both social mobility and the performing arts of the general election pledge, and to exempt children in receipt of government sponsorship.

The institution is currently home to 225 elite student ballet dancers aged 11 to 19 who combine a mainstream academic education with intense artistic training for up to four hours a day.

Regarded as one of the best ballet training schools in the world, most of its graduates go on to gain places in the Royal Ballet or other international companies.

The boarding fees - set by the Department for Education (DfE) - range from around £30,000 to £35,000 a year and financial support in the form of government and private grants is strictly means-tested.

It means that while the majority of children receive some assistance - some are 100 per cent supported - most families have to contribute to a greater or lesser extent.

When The Telegraph visited this week, the Year 11 students were taking a break from intensive ballet training to sit their GCSE exams.

All around them, however, preparations for the start of the main performance season - La Valse at Holland Park, among many others - were under way.

‘It would destroy opportunity’

Sitting in his office in the lower school’s majestic White Lodge campus, a Grade I Georgian hunting lodge set in the heart of Richmond Park in south-west London, Mr Gajadharsingh, the academic and pastoral principal, could not contain his frustration.

In common with independent heads across the country, he is anxiously waiting for Labour’s manifesto in the hope of gleaning how the VAT policy will affect the children under his care.

In the absence of any detail, however, he can only fear the worst.

“It would destroy opportunity,” he said bluntly.

“I can think of specific young people who come from typical working class families who have discovered a love for dance, ballet particularly, who would never have had an opportunity to develop that interest and that love, and are now professional dancers in companies around the world.

“It’s the Billy Elliot story,” he added. “That’s exactly what it is.”

The hugely popular film, released in 2000, tells the story of a working class boy from the north-east of England with a passion for ballet who battles through the prejudice of his coal-mining community to win a life-changing place at the Royal Ballet School.

The families who send their children to the school are, for the most part, not rich.

In fact, 40 per cent of students have parents with a combined income of less than £50,000 a year, while 28 per cent come from families earning less than £35,000.

Because the means testing is so rigorous, even less well-off parents pay what they can.

A 20 per cent tax raid could push many over the edge.

‘Rich kids’ risk

“A good number of our parents would just not be able to stand a 20 per cent increase on what they contribute at the moment,” said Mr Gajadharsingh.

The risk is that the school, arguably as pure an example of meritocracy as it is possible to find, becomes an institution for the better off.

Or, as the principal put it, a place “for rich kids who may not even be very good at dancing but can afford to come to the school”.

The unique infrastructure and staffing requirements of an elite ballet school come with an enormous cost base.

On top of the normal academic staff, a 20-strong healthcare team - comprising physios, nutritionists, Pilates instructors and others - work around the clock to keep the young athletes sound.

At the White Lodge lower school - the upper school is based in Covent Garden - they work in a lavishly equipped basement suite, replete with Pilates machines costing £5,500 a unit, weights and other specialist gym and rehabilitation equipment.

Erica Gethen Smith, a former professional dancer turned physiotherapist, explained the team had recently lost two members, one of whom had gone to work for Chelsea FC, the other to Brighton and Hove Albion.

“I think that flattered us,” she said. “It certainly shows the standard of athlete we’re looking after here.”

Then there are the dance teachers.

Fine margins

In a large, mirror-lined studio, Larissa Bamber, a former ballerina with the Royal Ballet, was leading a group of 16 Year 9 girls through their exercises while a professional pianist - the classes demand live piano, further adding to the cost - played Morning by Edvard Grieg.

The music stops abruptly and Ms Bamber, chanting “toes, toes, toes”, marches down the line of precariously poised young ballerinas, minutely correcting the angles of their outstretched feet.

The requirements of putting on ballet to the highest standard are endless.

Costumes are regularly ordered from across Europe.

Meanwhile, when specialist choreographers are called in to prepare the students for their public-facing performances, the school picks up the bill for their flights and accommodation.

It means fine financial margins.

“Depending on the impact of any potential increase in fees and subsequent student departures, we may well find ourselves in a position that would mean the quality of performance outcomes at the school may be compromised,” said Mr Gajadharsingh.

“I am sure that this is not a good look for any government, particularly when it concerns one of the flagship performing arts schools in the country.”

Even for non-vocational independent schools, the difficulty of planning around a policy for which there is currently no detail is a headache.

But for the Royal Ballet School, it’s a full-on migraine.

‘Politics of envy’

Currently, 58 per cent of students receive varying levels of government sponsorship under the Music and Dance Scheme, but it is not known whether these places will attract VAT, and if so whether the DfE would cover them.

Then there is the uncertainty around special needs pupils - around 40 at the Royal Ballet School are currently on the special needs register.

“I believe education should be something which is sacrosanct and protected, and a matter of parental choice,” said the principal.

“I think there’s a misconception out there that every private school is Eton or Harrow or Winchester, but they’re not.

“My gut instinct is this is the politics of envy. It won’t give them [Labour] the money they want or expect.”

In the entrance hall to White Lodge stands a life-sized bronze statue of arguably the school’s most famous alumnus, Margot Fonteyn.

Mr Gajadharsingh points out the middle finger of her outstretched hand, which is shinier than the rest of the statue.

“It’s a tradition we have here,” he said. “The students touch the finger on the way in for good luck.”

As he awaits the details of Labour’s flagship policy, he may well be tempted to touch it himself.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News