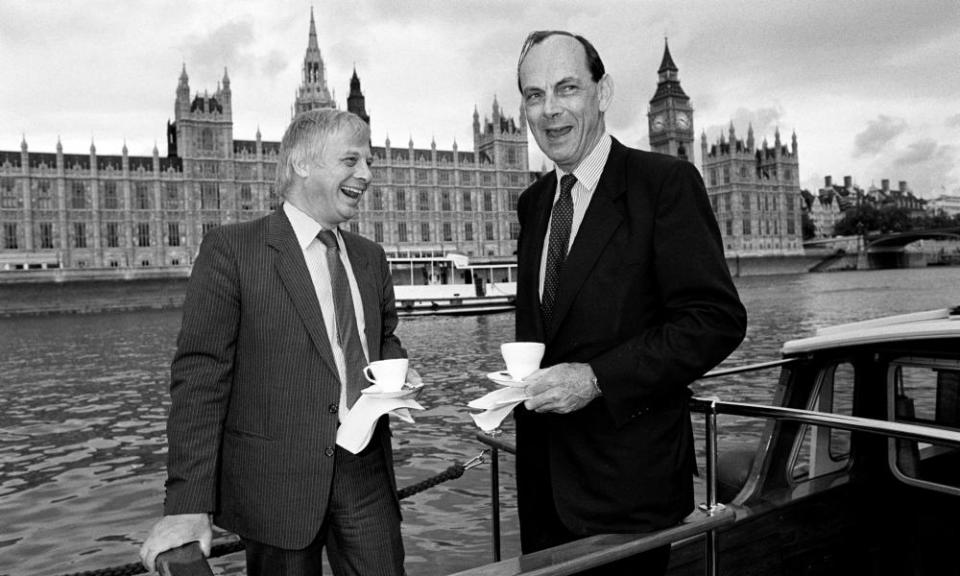

Lord Crickhowell obituary

Lord Crickhowell, who has died aged 84, was, as Nicholas Edwards, the Welsh secretary for eight years in Margaret Thatcher’s first two administrations. Representing the principality to the cabinet’s Thatcherites was not easy. He was known as “Big Stick Nick” to many across the Severn estuary, but he fought dogged internal battles with the unwilling Treasury to secure funding for Welsh projects, including most notably the Cardiff Bay barrage.

The scheme, initially opposed by conservationists and many Welsh politicians, including the city council, some prominent Labour politicians, local residents, Treasury ministers and Thatcher herself has, despite the initial cost which soared far beyond the original estimates of £50m to more than £200m, helped regenerate the southern part of the Welsh capital. Edwards supported it, foreseeing a venue for an opera house, but the area now incorporates not only the Wales Millennium Centre for the performing arts but also the Senedd, the Welsh assembly building. Though mocked at the time, Edwards rightly described the bay project as one of the greatest pieces of urban regeneration in the country.

Edwards, a tall, saturnine figure, spent almost all his 17 years in parliament as the Conservatives’ spokesman on Welsh affairs. He was of Welsh stock but he was born, son of Marjorie Ingham Brooke and Ralph Edwards, in London, where his father was the head of the woodwork and furniture department at the Victoria and Albert museum, and later an adviser on works of art to the Historic Buildings Council of England and Wales. Years later, arguing privately with Thatcher against cuts in arts funding, he would claim: “I was virtually brought up in the V&A and have known the art world all my life.”

The family had a home in the Black Mountains of south Wales as well as one in Chiswick, west London. Edwards was educated at Westminster school, before going to Trinity College, Cambridge, to study history after national service in the Royal Welch Fusiliers. After university, he went into insurance in the City and in due course became a Lloyd’s broker.

He was elected Tory MP for Pembroke at Edward Heath’s triumphant general election in 1970. It was a constituency that had supported Labour for 40 years, though one at that stage represented by the eccentric Desmond Donnelly, who had changed party allegiances several times. Edwards would hold the seat throughout his Commons career.

Once Thatcher became the party leader in 1975, Edwards’s business background and support for the new leader made him the opposition’s shadow secretary of state and he duly became Welsh secretary when the party returned to power in 1979. Wales was by no means a Tory-free zone: 11 Conservatives were elected to its 36 seats in that year (eight were elected in the 2017 general election in the principality’s now 40 constituencies) but Edwards’s Thatcherite economic stance ensured that he was her envoy to the Welsh.

The Welsh secretary’s dry economic credentials may have been apparent at Westminster, but in Wales he was pragmatic. Regional aid was cut, but there was special pleading for aid to the steel works at Shotton and, when Wales’s sole Plaid Cymru MP Gwynfor Evans threatened to starve himself to death to secure a separate Welsh language television service, Edwards conceded that too.

He was a keen supporter of the Cardiff Bay barrage project, despite pointed threats from the Treasury that he should keep quiet and warnings from Thatcher’s private secretary that it would be just another public sector folly. As he wrote to the prime minister: “I can hardly fail to express support for a proposal I personally have carried forward publicly … the proposal is fundamental to the successful development of south Cardiff.”

Edwards was equally vehement that the government should not be seen as philistine by cutting arts funding to the National Museum of Wales and Welsh National Opera while ladling it out to the new British Library and the opera in London. He told Thatcher in a private note released 30 years later: “Huge expenditure and the presence of international stars are not necessary to achieve high standards and cultural excellence – lessons that Covent Garden has apparently still to learn.”

He insisted that the Tories should not write off the arts world as entirely consisting of their political opponents. Though he recognised that he might be a lone voice crying in the wilderness, it was appalling politics and a social misjudgment: “The arts are important for themselves, not only a hostile political interest.” In 1995 he would lead the campaign for the WNO to have a permanent home in Cardiff, in opposition to the then Tory government.

As secretary of state, he travelled widely, seeking private sector investment in Wales and by 1987 his health was under strain. He decided to step down at that year’s general election. He was appointed to a life peerage and played an active part after that in the House of Lords.

In 1989 Crickhowell was made the first chairman of the newly established National Rivers Authority, even though he admitted he knew nothing of environmental science. Far from being a Thatcherite laissez-faire leader, he championed the improvement of water quality and the shaming – and, if necessary, prosecution – of industrial polluters.

Crickhowell was himself a freshwater angler and lived in a converted watermill in the Black Mountains. “Any organisation that thinks it may happily go on polluting our rivers and seas, or thinks that it is likely to get away with it scot-free would be making a very great mistake,” he told the Guardian in 1989. The first to be prosecuted was Shell. The NRA would be, he said, the strongest environmental protection agency in Europe and he led it until it was absorbed into the Environment Agency in 1996.

His ill-health did not prevent him taking up a string of business and cultural appointments. He returned to underwriting and other directorships at HTV, Anglesey Mining and Associated British Ports. And he served terms as president of the University of Wales, Cardiff, director of the Welsh National Opera, chairman of the Cardiff Bay Opera Trust, president of the Contemporary Arts Society for Wales and the South East Wales Arts Association.

He married Ankaret Healing in 1963. They had a son, Rupert, and two daughters, Sophie and Olivia.

• Roger Nicholas Edwards, Lord Crickhowell, politician, born 25 February 1934; died 17 March 2018

Yahoo News

Yahoo News