From Magna Carta to Brexit: 800 years of constitutional crises in Britain

LONDON (Reuters) - British Prime Minister Boris Johnson faces accusations of triggering the biggest constitutional crisis in decades after he announced that parliament would be suspended for around a month shortly before the country is due to leave the European Union.

While Johnson says it is customary for parliament to be suspended - or "prorogued" - before a government outlines its new policy priorities in a Queen's Speech, his opponents say the timing and length of the suspension is designed to sideline parliament in the countdown to Brexit.

Britain has an uncodified constitution, meaning it is largely upheld through convention and precedent.

The constitution has changed dramatically down the centuries, with monarchs steadily surrendering their once-vast powers to the government and prime minister of the day. Johnson required Queen Elizabeth's formal consent to suspend parliament but she was equally required, by custom, to grant it.

Following is a timeline of some major constitutional crises over the last eight centuries that have pitted the executive power - originally the crown and later governments acting in its name - against the legislative arm.

WHOSE CONSTITUTION? ENGLAND, BRITAIN AND THE UK

The story begins in the origins of England's constitution. England annexed the principality of Wales in the 1530s and then forged the Acts of Union with Scotland in 1707 to create Great Britain. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was formed in 1801 after the Acts of Union with Ireland, before the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922 left the "UK" as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

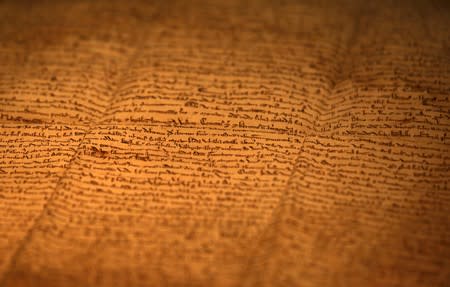

1215: MAGNA CARTA

Issued in June 1215, the Magna Carta was the first document to establish the principle that the monarch was not above the law and to place limits on royal power.

The charter, which King John was forced by his barons to sign, decreed that nobody should be denied the right to justice or subject to unlawful imprisonment, dispossession or exile.

John later persuaded the Pope to declare the document illegal and a civil war broke out. John died in October 1216 and his son Henry III eventually made peace with the rebels.

1529-1536: HENRY VIII AND THE REFORMATION PARLIAMENT

Jokingly referred to by some as the "first Brexit", Henry VIII's decision to break with Rome over his desire to divorce his first wife Catherine of Aragon split England from the Catholic Church and would fundamentally change Britain's relationship with mainland Europe.

Henry's 'Reformation Parliament' made laws affecting all areas of life, especially religion, which had previously been under the authority of the Roman Catholic Church alone. It established that parliament was "omnicompetent", that is, it had control over the whole of government, albeit under the monarch.

1642-1660: CIVIL WAR AND RESTORATION

Long-simmering tensions between the monarchy and parliament over money, religion and other issues came to a head in 1642 when King Charles I entered the House of Commons in a bid to arrest five lawmakers personally.

Civil war erupted, culminating in victory for the parliamentarians over the royalists and in the execution of Charles I in 1649 for high treason.

England became a republic. Oliver Cromwell, increasingly frustrated with parliament, also led an armed force into the legislature, dissolved it and ruled as Lord Protector until his death in 1658. Chaos then ensued and the monarchy was restored in 1660 under Charles' son, who became Charles II.

1685-1689: GLORIOUS REVOLUTION

In 1685, Charles' brother, a Roman Catholic, became James II and suspended parliament amid tensions over his bid to repeal anti-Catholic laws.

His use of the royal prerogative to suspend all religious penal laws without parliamentary approval prompted lawmakers to invite William of Orange, a Dutch Protestant, to invade England and take the throne.

A Bill of Rights passed in December decreed that only a Protestant could be monarch, a rule which is still in place now.

The so-called 'Glorious Revolution' marked the peaceful assertion of parliament's rights over the monarch.

1906-1911: ASQUITH AND LORDS REFORM

The landslide election victory of the Liberal Party in 1906 left them with a healthy majority in parliament's lower chamber, the House of Commons, but massively outnumbered by Conservatives in the unelected House of Lords.

Tensions came to a head in 1909, when the Lords rejected the Liberals' budget, which included taxes on large landowners, going against parliamentary precedent.

Though the Lords passed the budget in 1910 after a new election, Prime Minister Herbert Asquith introduced a bill to abolish the Lords' veto on finance bills and allow the Commons to force through other bills after a delay.

The government also sought to involve the monarch in politics, saying it might be necessary to create hundreds of new lords to pass the controversial bill through the chamber. The threat was eventually enough to pass the bill through the Lords.

Today the House of Lords remains an unelected chamber, though its members are now mostly appointees, not hereditary peers. Its role is to scrutinise legislation passed by the Commons and it can block bills for up to a year. The prime minister retains the power to create new lords.

(Reporting by Alistair Smout; Editing by Guy Faulconbridge and Gareth Jones)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News