'Major triumph': The story of one of the 'greatest events' in history of Glasgow

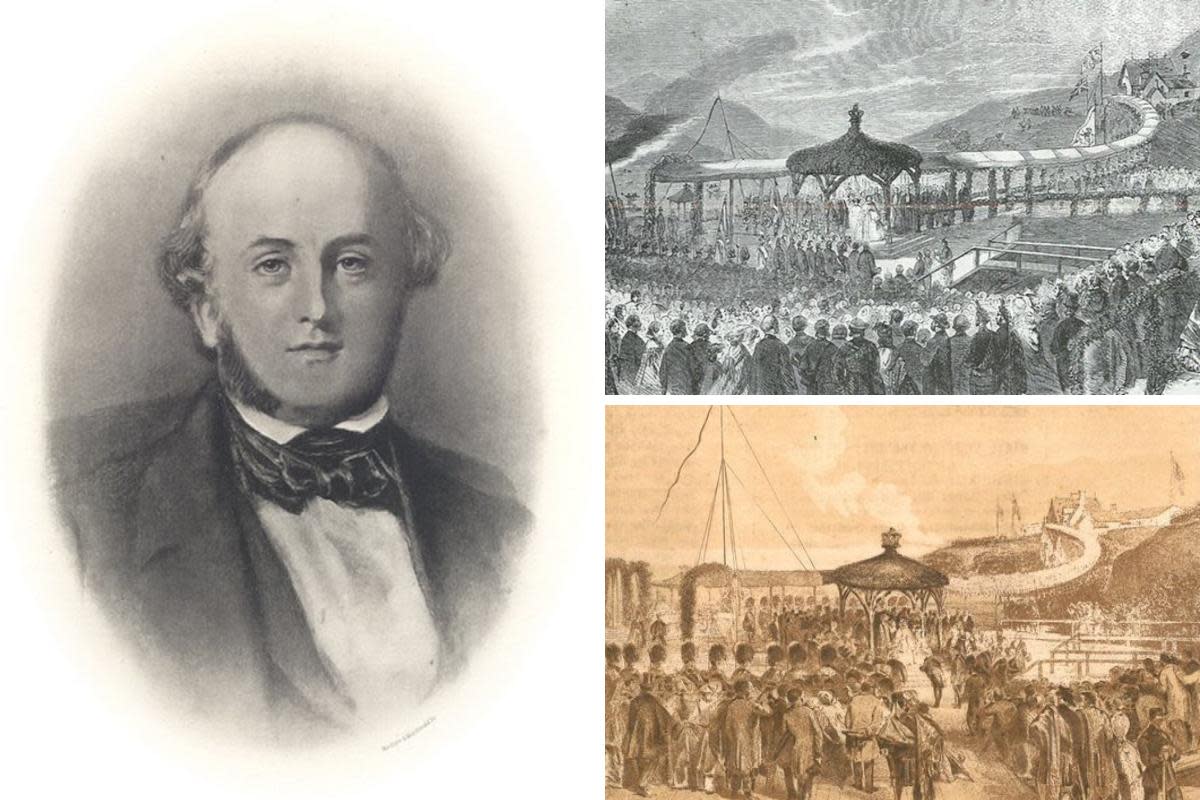

Robert Stewart of Murdostoun, the man who delivered clean water to Glasgow.

This was the major triumph of Mr Robert Stewart’s municipal career and one of the greatest events in the history of Glasgow.

Robert Stewart (1810-66) became a councillor in 1842. By 1845 he was an ordinary magistrate and two years later a senior bailie or acting chief magistrate.

(Image: Glasgow City Archives)

As chief magistrate in 1848, the year of disturbances and revolution across Europe, he played a prominent role in suppressing disturbances in Glasgow. The Colonel of the regiment of cavalry was called out and appeared with a squadron. An excellent equestrian, Mr. Stewart mounted the horse of an orderly dragoon and rode with the Colonel and his men into the very thick of the fray.

His role in quelling the disturbances was universally admired. In recognition of this contribution, he succeeded Sir James Anderson as Lord Provost in 1851, a time when the question of Glasgow’s water supply was uppermost in the Council’s concerns.

In the1700s, Glasgow drew its water supply from wells which were fairly plentiful in the district. With large-scale migration into the city in the early decades of the 1800s water supply became inadequate. In 1831 and 1832 the city was devastated by cholera and typhus when four thousand died. These epidemics occurred regularly, including 1849-1850 when 3800 died and 1853-4 when 3900 died.

Glasgow’s Lord Provost, Robert Stewart was the driving force behind the implementation of a municipally-owned water scheme to provide clean water to Glasgow’s rapidly increasing population.

Loch Katrine was identified as a suitable supply but there were objections from various parties both in and outside the Town Council. Opposition came from several chemists, including Professor Penny of the Anderson University, who believed that the Loch Katrine water was dangerous, and he produced examples of the water impregnated with lead.

Loch Katrine (Image: Glasgow City Archives)

With firmness and by conciliation, and with his eyes firmly on the prize, Mr Stewart and the others on the Water Committee beat back the opposition, and the measure was launched in Parliament.

It was, again attacked in a most determined manner. Counsel and witnesses, in the name of certain citizens of Glasgow, came to the committee room, armed with ‘scientific evidence’ and sundry bottles of Loch Katrine water, in which lead had been dissolved, to prove that the public would be in danger if the Highland water was brought into the city. The scientific evidence convinced the committee and the Bill was for the time being thrown out.

It was rescued from the scientists with a financial concession but met with a new difficulty in the form of the veto of the Admiralty.

Many thought the fate of the scheme was sealed forever.

Stewart was not to be thwarted. He had made friends with Lord Palmerston when he visited Glasgow in 1854 to receive the Freedom of the city. Stewart requested a meeting with Palmerston and under the guidance of the provost, he gained a full understanding of the whole scheme, concluding that the objection of the Admiralty was unfounded.

He reassured Stewart he would do all in his power to promote the objectives of the city. And he was as good as his word. After their conversation, the First Lord of the Admiralty went down to the House of Commons and declared his readiness to withdraw the veto.

By this time, the session was so far advanced that it was impossible to carry the Bill through the House of Lords. Stewart did not have long to wait as in 1855 the Loch Katrine Act was finally agreed. The scheme was opened by Queen Victoria in 1859 and was fully operational by 1860.

Perhaps it was fate but in 1866, the year of his death, the scourge of disease once again appeared in Glasgow.

(Image: Glasgow City Archives)

There were only 66 deaths which was the result of the large supply of clean water being brought to the city from Loch Katrine.

In 1872, Stewart’s campaign to pass the Loch Katrine Act was finally commemorated by the city with the Stewart Memorial Fountain in Kelvingrove Park.

Its sculpted designs tell the story of the city’s water and mark Robert Stewart’s contribution to the improved health of Glasgow citizens.

Memorial fountain (Image: Glasgow City Archives)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News