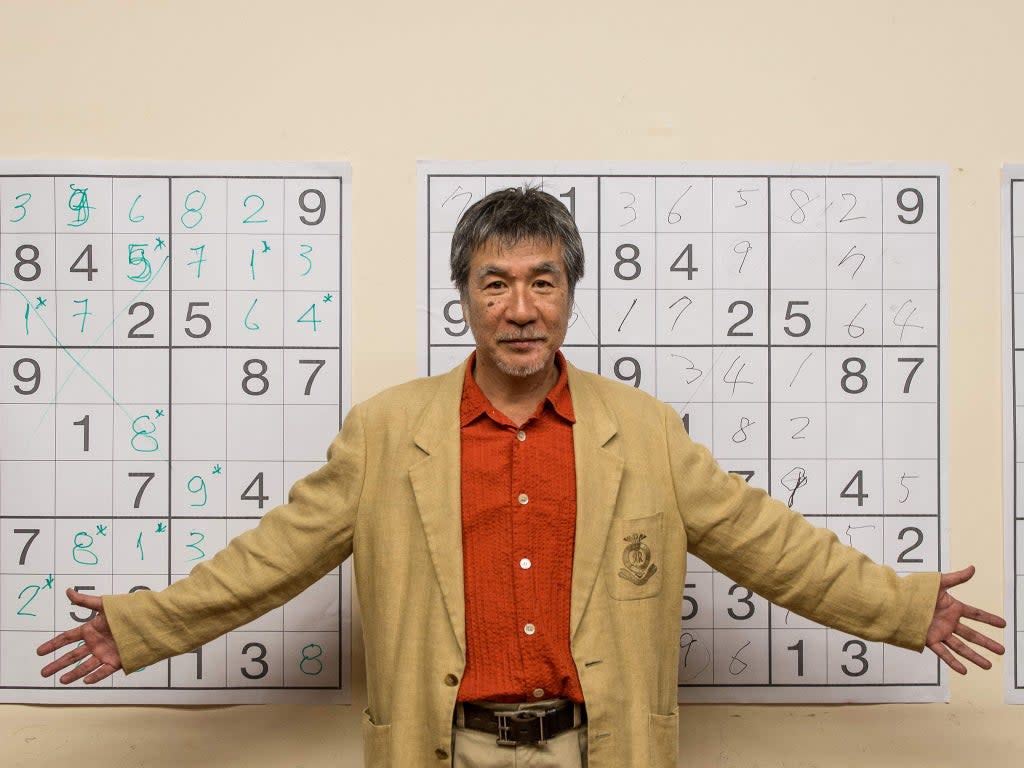

Maki Kaji: Godfather of Sudoku and puzzle enthusiast

Maki Kaji, a Japanese puzzle maker who became known as the “Godfather of Sudoku” for bringing the game to millions around the world, has died aged 69.

The puzzle, which looks relatively simple on paper but has the ability to leave even the most mathematical of minds stumped, is loved by people around the world, so much so that the Sudoku industry is worth an estimated £2bn.

A chance encounter with a US puzzle magazine in the mid-1980s brought Kaji onto his journey with the game. Number Place, believed to have been designed by 74-year-old retired architect Howard Garns, consisted of a 9x9 grid in which digits from one to nine would be filled in so each digit only appeared once in each row and column.

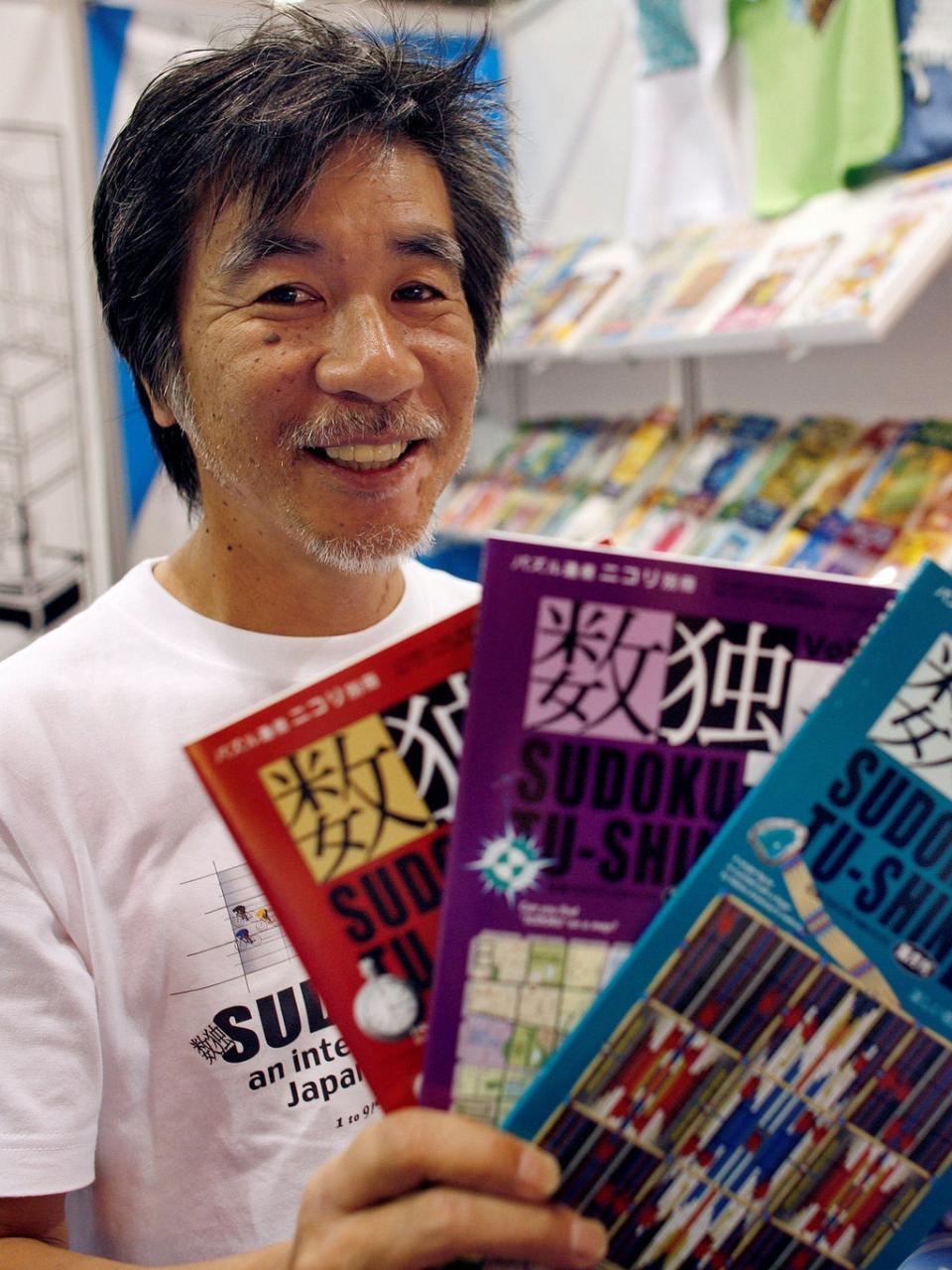

After solving the grid, despite having no idea how to read the English instructions, he knew he’d come across something special. Its simplicity on paper masked its true complex nature, something which delighted him. Very much the puzzle enthusiast, Kaji and two friends already published Japan’s first puzzle magazine, Nikoli. Logic games were their speciality and Number Place fit right into the niche publication.

Of course, the puzzle isn’t known by the rather lacklustre name “Number Place”. It was while rushing to a horse race that he came up with the name “Sudoku”, having already been told that Suuji wa dokushin ni kagiru (numbers should be single) was much too long. In 1984, Kaji’s modified version was published, although it initially received little fanfare outside of Nikoli’s niche readership.

Global popularity came thanks to Wayne Gould, a retired Hong Kong judge, who discovered a book containing one of Kaji’s puzzles in 1997. Six years later, after programming software that could generate Sudokus, Gould approached The Times with a proposal to begin publishing the puzzles. Intrigued by its design, the newspaper accepted and printed it for the first time on 12 November 2021.

Sudoku fever was swift – the puzzle was a raging success in The Times, with the Daily Mail and The Telegraph publishing their own versions. Newspapers across the UK followed suit as publications fought to capitalise on the puzzle phenomenon. During the summer of 2005, Sudoku collections appeared in bookshops across the globe, in as many as 30 countries. By 2007, this number rose to 90.

Gould, who became a good friend of Kaji, told the Financial Times: “Unlike a crossword, Sudoku does not test what you know, it just tests how you think … Cultural, ethnic, political, educational boundaries, none of them are relevant.”

Maki Kaji was born on 8 October 1951 in Sapporo, on the Japanese island of Hokkaido. His father was a telecoms engineer, while his mother worked in a kimono shop. The puzzle enthusiast attended Shakujii High School, which was followed by a literature degree at Keio University, Tokyo. However, he dropped out of the prestigious university after only a year, preferring to gamble and play tennis. Before setting up Nikoli, Kaji had stints as a waiter, a roadie and a construction worker.

Until stepping back in July due to his ailing health, he was heavily involved with helping his publication create more than 300 different games for its 50,000-strong readership. In an interview with The Japan Times, he said his favourite puzzles were the “ones with humour and pathos, ones you get angry with, that make you throw up your hands and cry, ‘I can’t do this’.”

When it came to creating the magazine, Kaji shunned computers and instead insisted on everything being created by hand. This would allow “the character and individuality of the writer … to come out”.

The global success of Sudoku meant that Kaji was in demand, but he would ignore calls from big companies to take over his publication, choosing to stay true to his passion. Sudoku wasn’t his only beloved creation: Slitherlink, a game requiring players to link dots in a loop without crossing, and Hitori, a logic game similar to Sudoku, were among many to gain popularity in Japan.

As an international figurehead of the puzzle, Kaji would travel around the world, whether as a spectator at international Sudoku championships or to sell his own versions of the game to publishers. His own personal collection of examples was vast, inspired by millions of combinations that could be created. Always one for humour, Kaji changed his business card to read “Godfather of Sudoku”.

He is survived by his wife, Naomi, and two children.

Despite the global success of Sudoku, Kaji never trademarked his game outside of Japan and as a result, never gained that much financially. However, he remained unbothered by this loss of money, saying: “More than the money, it is gratifying to see the explosive worldwide growth of our puzzles. That makes me very happy.”

Maki Kaji, puzzle make, born 8 October 1951, died 10 August 2021

Read More

‘Godfather of Sudoku’ Maki Kaji dies: How the puzzles help boost mental health

David Crossland: French-language teacher who became a crossword setter for The Independent

Yahoo News

Yahoo News