Manchester United 1999 treble xG breakdown: Bayern Munich, 1999 Champions League final

20 years on, it remains the greatest single-season achievement in English football’s history. But what would Manchester United’s treble of 1999 look like under a 21st century microscope?

In partnership with StatsBomb, The Independent has analysed three key games in United’s run-in in the hope of offering fresh perspective and insight on an iconic team and a historic achievement.

After analysing the FA Cup wins over Arsenal and Newcastle, we end with the most famous game of all from that 1998-99 campaign: the last-gasp Champions League final victory over Bayern Munich at the Nou Camp.

~ ~ ~

Manchester United 2-1 Bayern Munich

Champions League final

26 May 1999

Nou Camp, Barcelona

Match statistics

xG totals

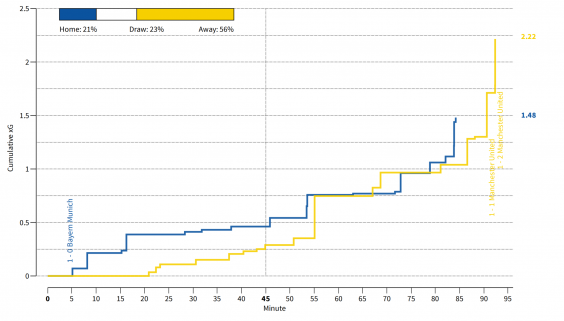

Where to start? Well, you already know the scoreline and it was reflected in the underlying statistics. United finished with 2.26 xG, compared to Bayern’s 1.54. The shot count was almost level: United’s 19 to Bayern’s 18.

As the cumulative chart above shows, the game was as close as it seemed to anyone watching. Bayern shaded the first half in terms of chance created, but United came back in the second. This was an even contest. Until stoppage time, that is.

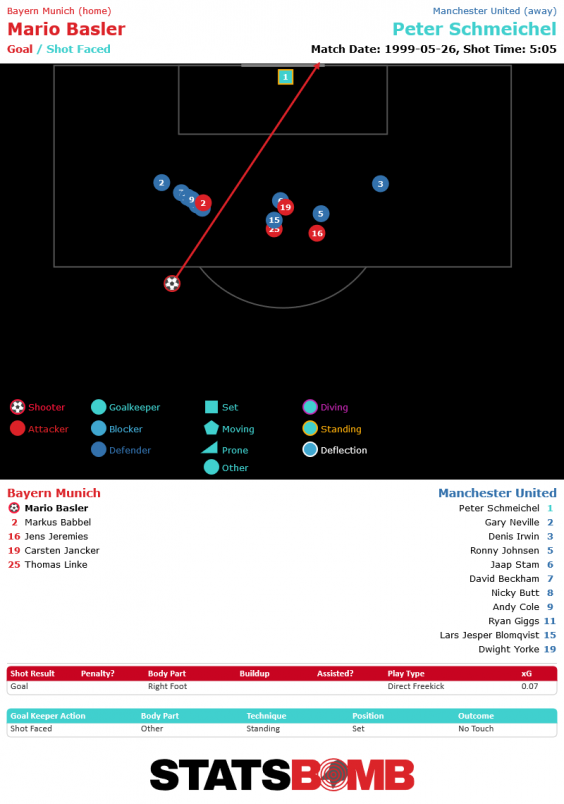

Basler, 6’

xG: 0.07

Before all that though, there is Bayern’s opening goal from Mario Basler’s free-kick – the game’s very first shot and one with a low xG value of 0.07, according to StatsBomb’s expected goals model.

It curves around a wall that, in hindsight, is slightly out of position. Peter Schmeichel takes a step to his right as the ball goes left, which perhaps leaves him unsighted and unable to dive. Markus Babbel’s disruption of the wall helps too.

Even so, it is the type of chance that only goes in one in 15 times. The shot is saveable, bouncing on the ground before tucking into the far corner. Given how he smacked his hands together after watching it beat him, Schmeichel knew he could have done better.

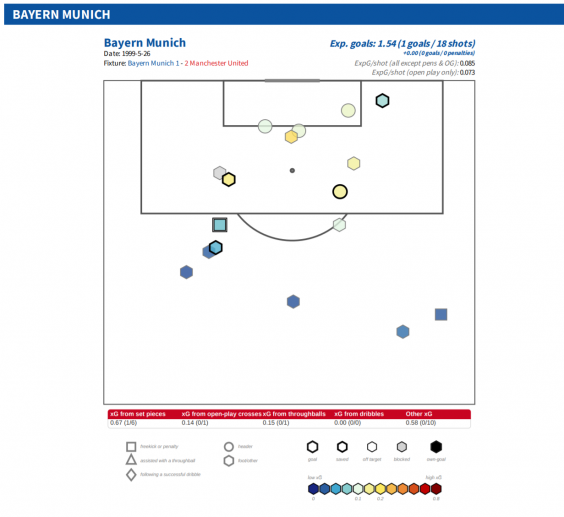

Bayern’s shot locations

As we have seen previously, 1999 was a time when top teams were more willing to shoot from range. And given they were 1-0 up for the majority of the evening, perhaps Bayern felt they could afford to try their luck.

Not one of their chances scores more than 0.25 xG on StatsBomb’s model. Their best is Carsten Jancker’s overhead kick, late on and from the edge of the six-yard box, which struck the crossbar.

Yet just because Bayern took a lot of low-value shots does not mean they did not come close to scoring with them. Mehmet Scholl’s chip from outside the box was rated 0.06 xG, yet beat Schmeichel and bounced back off the post.

In the second half, Basler almost caught Schmeichel off his goal-line with a 0.01 xG shot from just inside United’s half. Schmeichel stumbled on his way back to goal and watched the ball drop only a few yards over.

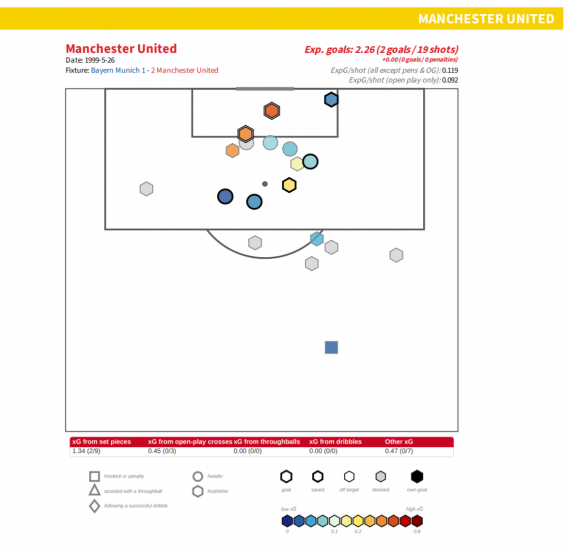

United’s shot locations

In contrast to Bayern, and perhaps because they were chasing the game for so long, United generally refrained from shooting at range and looked to work the ball into advantageous scoring positions.

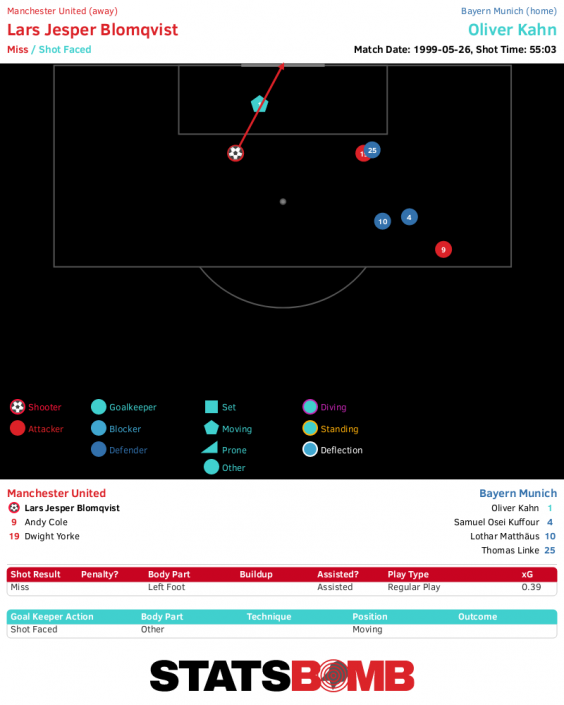

They could have equalised earlier through Jesper Blomqvist. Ryan Giggs, deployed as an inverted winger on the right, cut inside and crossed for the man playing in his usual position out on the left. While sliding to reach the pass, Blomqvist put a two-in-five chance wide.

“He couldn’t quite take Manchester United’s best chance of the night so far,” noted Clive Tyldesley on commentary. Tyldesley was right. It was United’s best chance up until that point. It would be the best they created in the regulation 90 minutes.

But, as the fourth official held up the board to indicate an additional three minutes, there were still two excellent United chances to come.

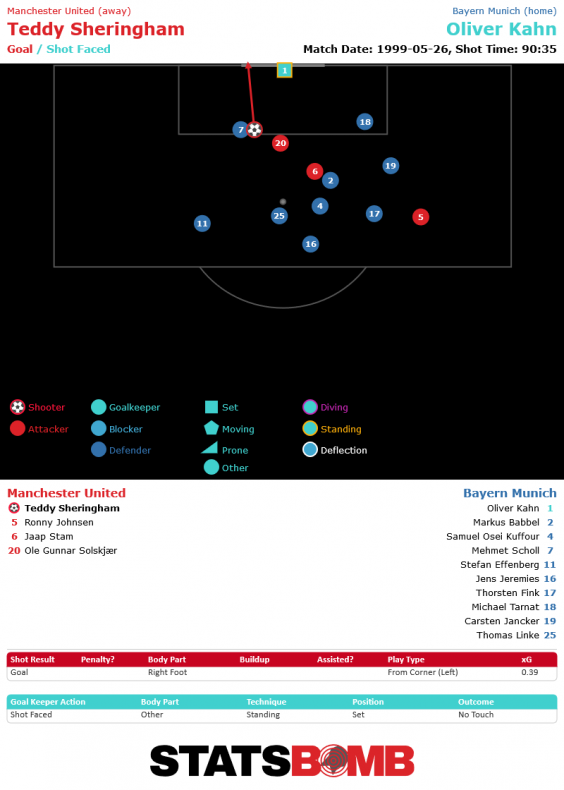

Sheringham, 90+1’

xG: 0.39

Blomqvist was replaced by Sheringham not long after his miss. In the breakdown of the FA Cup final, we noted how influential Sheringham was when appearing off the substitutes’ bench. For the second time in the space of four days, he came on to score and assist.

Whereas both goals against Newcastle were examples of the ‘99 United’s fine build-up play, this is a scrappy one, born out of Bayern’s inability to clear their lines properly and Sheringham hanging off the shoulder of Scholl, hoping to feed on any scraps that come his way.

Coincidentally, this chance had the same likelihood of being converted as Blomqvist’s. The key difference is perhaps that while Blomqvist was stretching to connect, Sheringham was stationary and could use his own momentum to guide Giggs’ initial shot in.

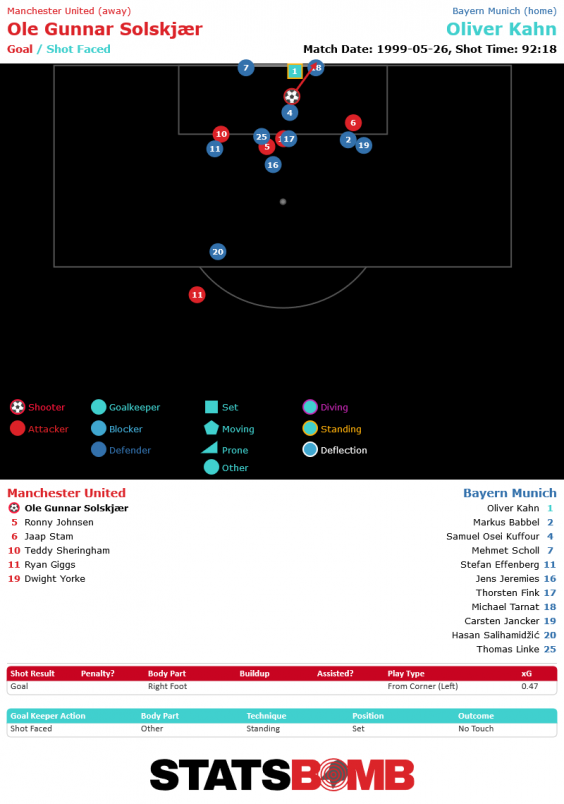

Solskjaer, 90+3’

xG: 0.47

United saved their best chance of the game until the last minute of stoppage time. With an xG of 0.47, this is essentially a coin flip to win the European Cup, weighted slightly against Ole Gunnar Solskjaer.

He is around four yards out, looking to lose Samuel Kuffour and, when Sheringham knocks the ball down, Solskjaer only appears to be onside because of Scholl and Michael Tarnat’s presence on the Bayern posts.

But Scholl, goalkeeper Oliver Kahn and in particular Tarnat cause him a problem, narrowing the space in which he has to score. His placement could hardly be any better. Whereas Sheringham found the bottom left, he finds the top right.

How unlikely was all this?

Were it not for the late flurry and had they lost 1-0, United could not have much to complain about. Bayern did not create a lot in the way of clear-cut chances, as the underlying numbers demonstrate, but they still came within a few inches of establishing a 3-0 lead.

United, meanwhile, struggled to fashion many threatening chances until they absolutely had to. Their only real chances of note before stoppage time were Blomqvist’s and a Sheringham snap-shot in the box that was easily held by Khan.

Historically, goals from corners are converted around 2-3% of the time.

But thanks to David Beckham’s delivery, some questionable Bayern defending, the instincts of Solskjaer and Sheringham plus the right bounce here or there, they created and scored through two excellent opportunities at the death.

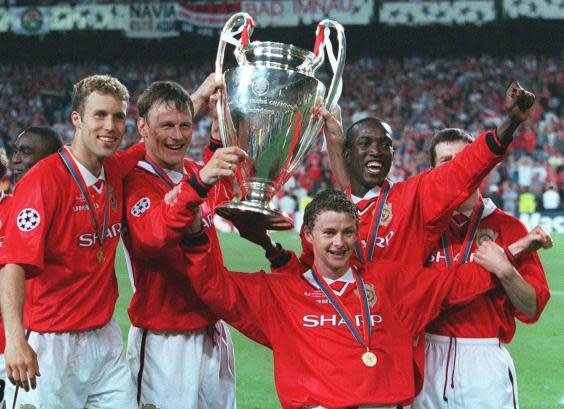

Historically, goals from corners are converted around 2-3% of the time. To score two in a row at any time of any match is remarkable. To score them in stoppage time to win a Champions League final and complete a league, cup and European treble is simply extraordinary.

You might say that there was nothing ‘expected’ about Sheringham and Solskjaer’s goals at all. The sheer improbability of what United’s 1999 team achieved in those 103 seconds between equaliser and winner is why they are still celebrated and revered, two decades on.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News