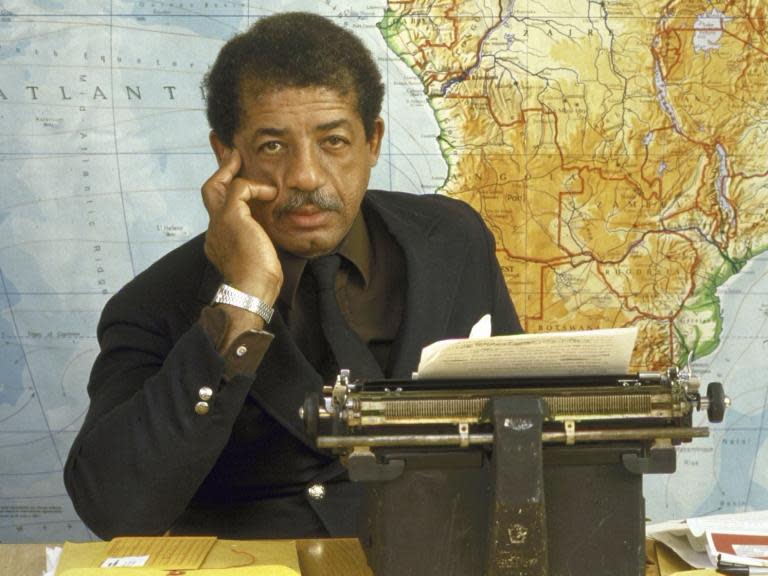

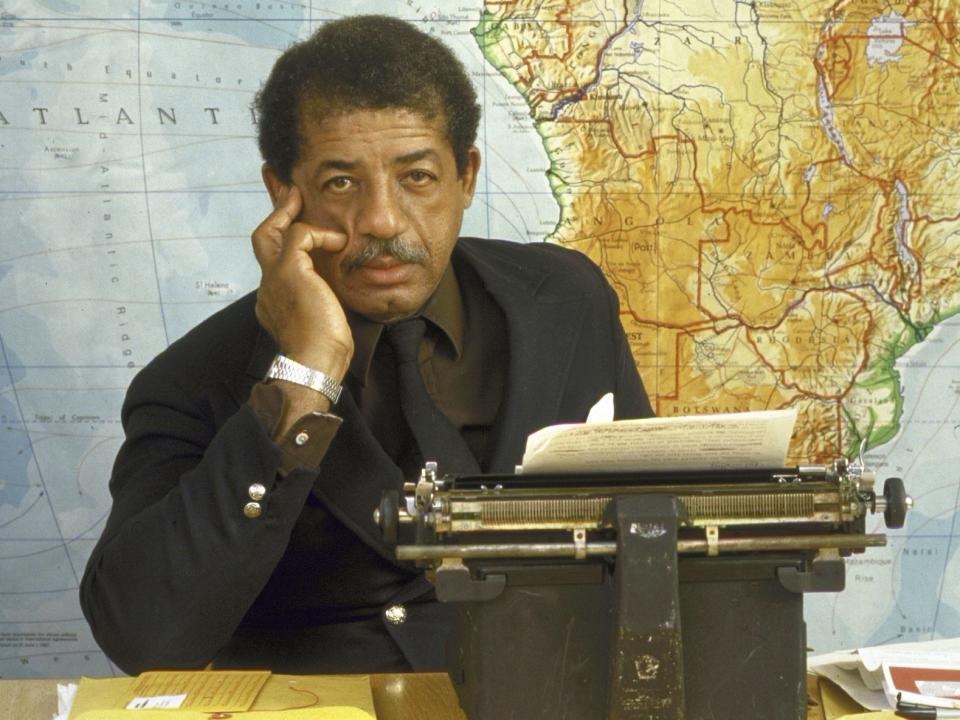

Martin Kilson: The first tenured black professor at Harvard

Martin Kilson, a political scientist whose scholarly interests included African politics and the history of African American intellectual life, entered graduate school at Harvard University in 1953, joined the faculty in 1962 and became a full tenured professor of government in 1969. He helped lay the foundation for collegiate black studies departments, which he sometimes criticised for a lack of academic rigour.

Almost two decades earlier, as an undergraduate at Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University, he met historian and activist WEB Du Bois, who was the first African American to receive a doctorate from Harvard. Kilson became one of Du Bois’ most prominent intellectual descendants and often highlighted the importance of an educated black elite – what Du Bois called the “Talented Tenth” – to promote African American cultural and social advancement.

By the mid-1960s, Kilson had helped found the Harvard-Radcliffe Association of African and Afro-American Students and was seeking to establish the study of African American life as a new field of academic inquiry.

He fostered what he called the “romantic notion ... that Negroes share a culture” and “should care about each other,” he told the Harvard Crimson student newspaper in 1964.

“I suppose we’re looking for a new Negro identity, a psychological process, which has its roots in a broader Negro community,” he said. “The Negroes, like the Jews, want to say something and contribute to the American mainstream.”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Harvard and other universities recruited greater numbers of African American students and faculty members and set up departments of black studies. Kilson, who helped launch the field, soon grew disenchanted with the direction of some of those programmes. He was concerned that academic standards were being lowered and he disparaged campus militants as “dilettantes jumping on the bandwagon and acting out all the trappings of something new and exciting”.

Kilson was especially disturbed by what he considered a trend towards self-separation and isolationism among black students at predominantly white colleges, arguing that they should engage with the wider academic world.

“I am opposed to proposals to make Afro-American studies into a platform for a particular ideological group,” he said in 1969, “and to restrict these studies to Negro students and teachers.”

In a controversial 1973 essay, Kilson argued that Harvard had admitted some unqualified black students and that the university’s black studies programme showed “slight concern for the academic standards that prevail at Harvard generally”.

Academically ambitious African American students, he said, “were forced to choose between their subcommunity and the university in general”. The result was racial tension on campus and “a nearly disastrous impact on the academic achievement and intellectual growth of Negro students”.

Early in his career, Kilson’s ideas of advocating for African American studies and for more black students at elite colleges were seen as radical. But his scornful view of politicised black studies programmes prompted an outcry from students, administrators and other professors, some of whom openly disparaged him as an “Oreo” or being “black on the outside and white on the inside.”

Kilson stood his ground and continued to pursue his academic interests. In 1975 he published a major book on African politics, New States in the Modern World, and the following year was co-editor of a book of essays, The African Diaspora – the first time the term came into widespread use.

Often at odds with the leaders of Harvard’s black studies programme, he finally gave it his blessing in the 1990s after Henry Louis Gates Jr became its director.

During almost 40 years of teaching at Harvard, Kilson mentored scores of students who went on to make a major mark on public life. His proteges included Mark Whitaker, who became the top editor of Newsweek magazine, and Cornel West, a leading African American intellectual now on the Harvard faculty.

“He took me in, as pupil, as student,” West said in a 2017 video tribute in which he described Kilson as his most influential teacher. “He exposed me to a cosmopolitan world of the life of the mind. He exposed me to an international dialogue about justice, about power, about structures and institutions.”

Martin Luther Kilson Jr was born on 14 February 1931, in East Rutherford, New Jersey, and grew up in Ambler, Pennsylvania. His father was a minister, his mother a homemaker.

He graduated first in his class in 1953 from Lincoln University, a historically black institution in the area of Oxford, Pennsylvania. As a graduate student of political science at Harvard, he conducted research in West Africa, receiving a master’s degree in 1958 and a doctorate in 1959.

His first book, Political Change in a West African State: A Study of the Modernisation Process in Sierra Leone, was published in 1966. He was an editor of numerous books, including the two-volume The Africa Reader (1970).

In 1979, Kilson received an official reprimand from Harvard after a female student accused him of sexual harassment.

He retired from teaching in 1999 but stayed on as emeritus professor for many years.

Kilson died on 24 April at a hospice centre in Lincoln, Massachusetts. He was 88. The cause was congestive heart failure, said his wife of 59 years, Marion Kilson.

Survivors include their three children, Hannah Kilson of Boston, Jennifer Kilson-Page of Brookline, Massachusetts, and Peter Kilson of Waltham, Massachusetts; a sister; six grandchildren; and a great-granddaughter.

After helping organise Harvard’s WEB Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research, Kilson delivered the university’s annual WEB Du Bois lecture in 2010. His 2014 book, Transformation of the African American Intelligentsia, 1880-2012, won the American Book Award.

“Martin Kilson has given the academy a great gift,” Gates, the Harvard professor, wrote in an introduction to that book, “not only in offering up the wisdom of ages but in writing a synthetic historical analysis of the indispensable role black intellectuals have played in shaping the African American experience.”

© Washington Post

Yahoo News

Yahoo News