Millions in South Africa Grow Old With HIV in Health-Spending Time Bomb

(Bloomberg) -- Yvette Alta Raphael radiates vitality and she isn’t old. But she grapples with brittle bones, aching knees and a vertigo so severe she’s had to stop driving for fear of causing an accident.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Russia Is Sending Young Africans to Die in Its War Against Ukraine

Putin Is Running Out of Time to Achieve Breakthrough in Ukraine

Macron Gambles on Snap French Election in Bid to Stop Le Pen

The 49-year-old entrepreneur is part of a generation of South Africans who have lived with HIV for decades and are now the first to grow old with the virus after revolutionary drugs turned a death sentence into a chronic ailment.

As they age, the cost of care is snowballing and millions are wondering what’s in store for them after critical elections left the country in political flux, with key differences over how to shore up a health-care system already wrestling with the world’s largest HIV epidemic.

Raphael, who owns a vibrant clothing store in Thembisa, a township bordering Johannesburg, remembers thinking when she first found out she had HIV that a lifetime on treatment probably meant five years at best. It’s now been more than 24 years, during which she got married, had two children and fulfilled her dream of opening her own shop.

“My biggest fear now is living for many years with the compounded ailments of aging,” Raphael said in an interview. “The government doesn’t care. They are like, ‘We saved you to be a burden on us again?’”

The potential costs are staggering for a nation that already spends as much as 9% of its gross domestic product to fund a part-private part-public health care system, with outlays per person well above those of any other country in sub-Saharan Africa.

In last month’s elections, the African National Congress ceded its parliamentary majority for the first time since it first took power under Nelson Mandela in 1994. Without an outright winner, the ANC must decide whether to form a coalition, but some of the biggest potential partners have starkly different views on a range of issues including its proposals to create a state fund to cover the health costs of all South Africans.

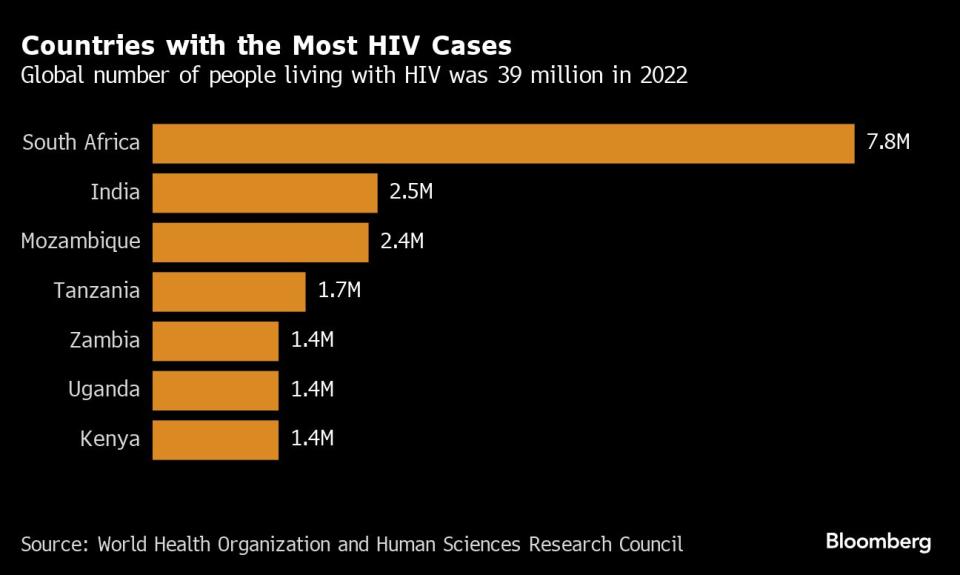

The longer government takes to address the needs of those aging prematurely with HIV, the bigger the financial drain in a country where 7.8 million people, or almost 13% of the population, live with the virus.

“Figuring out how to treat HIV and aging is complicated,” says Francois Venter, a professor of medicine at Johannesburg’s University of the Witwatersrand, yet he pointed to some first steps, like alleviating inflammation and risks such as cardiovascular disease.

A woman around Raphael’s age who visits a clinic to get her antiretroviral medication should, for instance, be assessed for potential heart conditions as well as screened for various kinds of cancer.

“It is becoming important that primary health-care clinics where HIV is also treated has the awareness that somebody who’s aging might have other health issues,” says Linda-Gail Bekker, chief executive officer of the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation in Cape Town. She also recommends monitoring people’s balance and hand-grip strength, which can indicate early aging.

South Africa spends about $1.8 billion a year to treat people with HIV and AIDS, according to UNAIDS. The program estimates that 15% of all government expenditures are for health, compared with 3.5% in India, the country with the second highest number of HIV cases.

That’s not nearly enough, according to Bekker. But estimating exactly how much funding is needed is difficult. The World Health Organization “is just beginning to grapple with this,” she says. The Geneva-based agency declined to give an estimated amount, saying by email that it “is exploring interventions targeting the geriatric population.”

The Department of Health says the government is aware of the advantages of integrating non-HIV services into HIV programs but it would need more evidence regarding the cost-effectiveness of focusing on early senescence in people living with the virus. It’s also grappling with the growing burden of tuberculosis and non-communicable disease like cancer and diabetes.

The question isn’t just funding, but infrastructure. More than half of South Africans live below the poverty line, which makes accessing regular treatment tricky, all the more so for someone who is struggling to move around. There are limited options for transport to clinics and long waiting periods, which adds to the burden.

Another kind of disparity — gender-related — is at the root of the problem. Many babies have been born with HIV because the virus disproportionately affects women. By the time they reach their mid-twenties, these people have lived with the virus for decades and may already be struggling with aging-related issues such as difficulty walking up stairs. Some of that stems from HIV, and some from the therapy.

At the moment, the country has no special services or programs for older people (or those aging prematurely) at the primary-care level, so they must compete with other patients for care.

How South Africa addresses early aging among HIV-positive people could offer a template for other countries on the continent such as Mozambique, Uganda and Zambia, which also have young populations that may live decades with the virus.

Raphael, for her part, says treatment with antiretrovirals allowed her to lead a fulfilling life that included traveling the world in search of new materials and styles for her store. But getting to a point where large-scale treatment was available required years of activism.

Besides running her shop, Raphael heads a national advocacy group for the prevention of HIV and AIDS. Lately she has campaigned to broaden the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis, a medicine that cuts the risk of getting the virus. She expects care for those aging with HIV will also require a fight, one likely led by women.

“We had to shame our government to get ARVs, we will probably have to shame them again to get care as we age,” Raphael said. These days, as she struggles with balance, she tells her now young adult children: rather a mother with vertigo than no mom at all.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

Legacy Airlines Are Thriving With Ultracheap Fares, Crushing Budget Carriers

Sam Altman Was Bending the World to His Will Long Before OpenAI

As Banking Moves Online, Branch Design Takes Cues From Starbucks

David Sacks Tried the 2024 Alternatives. Now He’s All-In on Trump

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News