Mohamed Morsi obituary

Though in 2012 Mohamed Morsi became Egypt’s first democratically chosen president, a year later he was overthrown by the military and held in prison on a series of convictions. He has died at the age of 67 after collapsing in court during a retrial of charges of espionage with the Palestinian Hamas organisation.

In 2011 a revolution had ousted Hosni Mubarak, Egypt’s president since 1981. Elections in June the following year brought the Muslim Brotherhood to power. The new president was the Brotherhood’s Morsi, who defeated the former prime minister, Ahmed Shafiq, with 51.7% of the vote, vowing that he would be inclusive and maintain Egypt’s 1979 accord with Israel. Morsi was actually the Brotherhood’s second choice; their first, Khairat al-Shati, was disqualified by the election commission for having served a prison term under Mubarak.

Once he was in power, Morsi’s stubborn Islamist policies brought protesters back into the streets in such huge numbers that in July 2013 the army sacked the government, arresting Morsi and fellow Muslim Brothers. Three senior officers marched into Morsi’s office, where he was holding a crisis meeting. Told he was no longer president, he burst into uncontrollable laughter. “It’s unacceptable what’s going on. This is a coup,” he shouted. He was taken to the headquarters of the Republican Guard in eastern Cairo, where many of his supporters were later gunned down by the army.

As president, Morsi had had no clear plan for economic recovery in Egypt, apart from cash injections from Qatar and other allies. He failed to clean up the notorious security apparatus, which continued to torture and kill protesters, and appealed to his electorate by maintaining expensive food and fuel subsidies, thereby critically reducing reserves. His followers attacked Egypt’s Coptic and Shia minorities and upset liberals by threatening to close shops by 10pm, in a country that lives by night, to help citizens attend the dawn prayer. He imposed a Muslim Brother as culture minister. His one foreign affairs achievement was to help broker a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas.

In August 2012, Morsi replaced Hussein Tantawi, the army chief-of-staff. He stripped the military of its say in drafting the new constitution and in December the Islamist-dominated constituent assembly approved a draft constitution that boosted the role of Islam and restricted freedom of speech and assembly. Protesters were particularly outraged by a constitutional decree that placed Morsi’s decisions beyond judicial review. Although he later cancelled the decree, the die was cast. He seemed unable to deal with the breakdown of law and order, or to listen to critics who feared that the Brotherhood was using its democratic honeymoon to impose an Islamist constitution, in place of the existing, secular “deep state”.

Worst of all, he appointed seven regional governors from the Brotherhood, and one, for Luxor, from Gamaa Islamiya, the extremist Islamist group responsible for the massacre of tourists at Luxor in 1997. After inter-religious killings, the Coptic pope, Tawadros II, accused Morsi of reneging on his promise to protect Christians. By June 2013 Morsi was at loggerheads with Muslim and Christian clerics, the judiciary, the police, the intelligence services and, crucially, the army.

As protesters lined the streets demanding an end to Morsi’s presidency, on 1 July the army delivered an ultimatum that required Morsi to resolve the political crisis within 48 hours. When he failed, on 3 July it overthrew Morsi, installing Adly Mansour as the interim head of state in his place until the installation of Abdel Fatah el-Sisi in 2014, and ordering the arrest of many members of the Muslim Brotherhood.

The eldest of five brothers, Morsi was born in the village of El-Adwah in northern Egypt. His father was a poor farmer; Morsi remembered being taken to school on the back of a donkey. He graduated with a BA in engineering from Cairo University in 1975 and an MA in metallurgy in 1978.

That year, he married his 17-year-old cousin Naglaa Mahmoud. She later told a magazine that he helped with household chores and cooked for her. “I like everything about him,” she said. “Our fights never lasted for more than a few minutes.” Morsi told an Egyptian television channel that marrying her was “the biggest personal achievement of my life”.

He joined the Muslim Brotherhood in 1979. Morsi lived in the US for several years: he studied for a doctorate at California State University, Northridge, where he was an assistant professor of engineering from 1982 until his return to Egypt in 1985. Then he served as head of the materials engineering department of Zagazig University, where he remained a professor until 2010.

Morsi was a member of Egypt’s parliament from 2000 to 2005, standing as an independent, since candidates were forbidden to run under the Brotherhood banner. The Brotherhood’s political wing, the Freedom and Justice party, was founded in the wake of the 2011 revolution, and Morsi became its first president.

In November 2013 Morsi was put on trial, charged with incitement to murder, and at a preliminary hearing questioned the validity of the court, saying, “What is happening now is a military coup. I am furious that the Egyptian judiciary should serve as cover for this criminal military coup.”

In April 2015, Morsi was sentenced to 20 years over deaths during clashes between opposition protesters and Brotherhood supporters outside the presidential palace in Cairo in December 2012. He was cleared of inciting the Brotherhood to kill two protesters and a journalist – a charge that could have carried the death penalty.

A month later, he was sentenced to death after being convicted of colluding with Hamas and Hezbollah militants to organise a mass prison break during the uprising against Mubarak, and in June the sentence was upheld after consultations with Egypt’s grand mufti. In November 2016 the court of cassation ordered a retrial of that charge and others relating to foreign organisations.

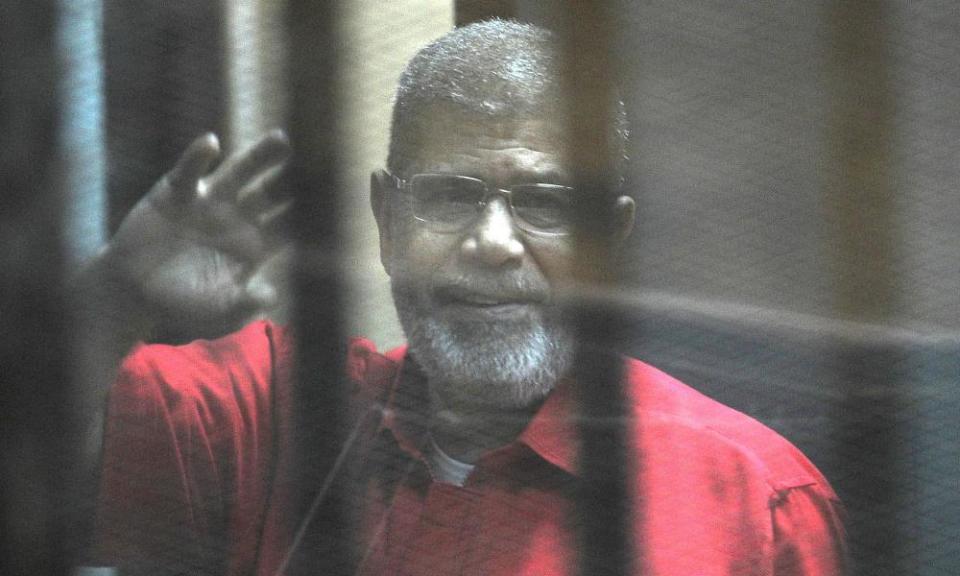

Morsi also faced charges of endangering national security by leaking state secrets to Qatar, fraud and insulting the judiciary. After being accused of disrupting his first trial by shouting protests, Morsi was compelled to sit in a soundproof glass cage in court. Shortly before his collapse he is reported to have told the court that he knew “many secrets” that, if revealed, would enable him to be released, though would not disclose them because doing so would harm Egypt’s security. He insisted that he was still the country’s legitimate president.

Morsi and his wife had four sons, Ahmed, Omar, Osama and Abdullah, and a daughter, Shaimaa.

• Mohamed Morsi Issa al-Ayyat, politician, born 20 August 1951; died 17 June 2019

Yahoo News

Yahoo News