Nearly 20 million children missing out on routine vaccines, UN warns

At least 20 million children worldwide missed out on lifesaving vaccinations last year due to a combination of conflict, lack of access and complacency, the United Nations has warned.

Global coverage for childhood vaccines including diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DTP3) and measles has stagnated at roughly 86 per cent since 2010, well below the 95 per cent required to avert outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.

According to data from Unicef and the World Health Organization, vulnerable children living in remote rural areas, urban slums and unstable regions are disproportionately affected by gaps in coverage.

Almost half of children who missed out on the DPT3 vaccines live in just 16 fragile or conflict-ridden countries – including three million infants in Nigeria, 1.4 million in Pakistan and 955,000 in Ethiopia.

Health systems in these regions are often crippled and children who do become ill are less likely to access the treatment they require.

“Immunisation is a public health magic bullet - or as close to one as there can be,” Dr Robin Nandy, chief of immunisation at Unicef, told the Telegraph. “It is a widely available, inexpensive intervention and it’s a real tragedy that we continue to see people suffer and die from preventable diseases.

“But having reached a global average of 86 per cent vaccination coverage, the children that remain unvaccinated are by definition harder to reach, and the same such strategies that got us this far are not going to work.”

Even within countries with high immunisation rates, outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases can reveal gaps in coverage and stark disparities in access to vaccine services.

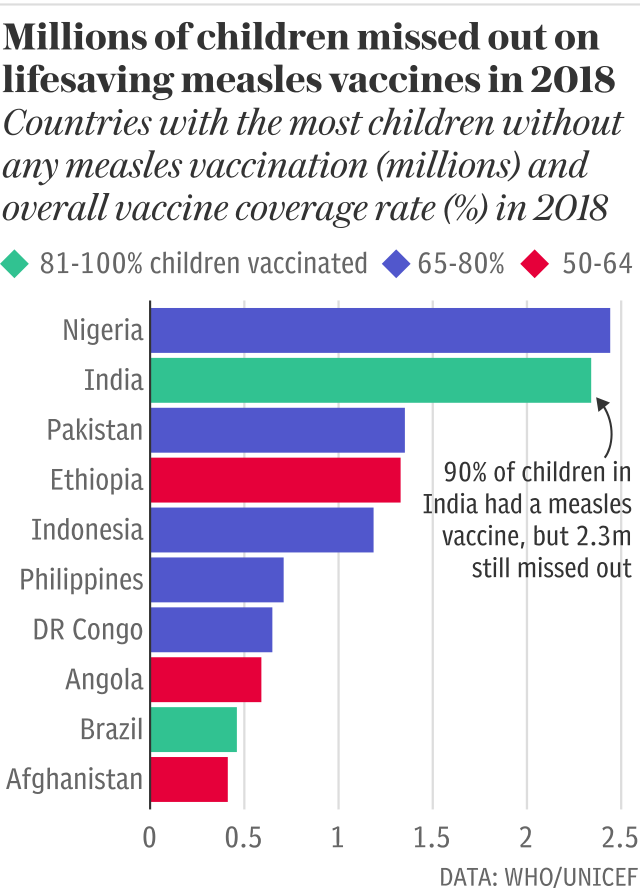

In 2018, measles outbreaks emerged all over the globe and almost 350,000 cases were reported – more than double the total in 2017.

“Measles is a real time indicator of where we have more work to do to fight preventable diseases,” said Henrietta Fore, Unicef's executive director. “Because measles is so contagious, an outbreak points to communities that are missing out.”

In India 90 per cent of children received at least one measles vaccine in 2018, but there were still more than 2.3 million unvaccinated. Last year the country recorded some 70,000 cases of measles, roughly a fifth of all infections worldwide.

“India is challenging from the numbers perspective to start with, so 10 per cent unvaccinated translates to a large number” said Dr Nandy. “But these children are often distributed in pockets, particularly in high density urban slums, creating a pool of susceptible children and regular measles outbreaks. It can be very difficult to reach them.”

But while it is low income countries that have the lowest vaccination rates – with less than 40 per cent of children vaccinated against measles in Equatorial Guinea, Samoa and Chad – developed countries are not immune.

In the UK only 92 per cent of children received the first dose of the measles vaccine, meaning some 62,000 children missed out – almost 6,000 more than in 2013.

And roughly 311,000 infants in the United States, which is in the midst of several outbreaks, did not receive a routine measles vaccine.

This is largely due to growing mistrust, rather than a lack of access. This year the WHO included ‘vaccine hesitancy’ in its list of the top ten global health threats for the first time, and according to the Wellcome Trust developed countries are the most sceptical.

“While availability, cost and access to vaccinations remains the biggest global obstacle, in high-income countries like the UK, the proliferation of vaccine-related misinformation on digital and social platforms is one of the key factors associated with vaccine hesitancy,” said Alastair Harper, director of advocacy at Unicef UK.

“Anti-vaccination groups are exploiting parents, creating confusion and stoking their fears in order to disrupt regular childhood vaccination schedules.”

In France – where more than 72,000 children missed out on measles vaccines in 2018 – a third of people do not believe that vaccinations are safe and 20 per cent think that they are not effective.

The country saw a 426 per cent increase in measles infections in France last year, when nearly 3,000 cases were recorded.

Commenting on the new data, Dr Seth Berkley, CEO of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, said: “Vaccines are now more accessible, affordable and effective than they’ve ever been – no parent should still be forced to go through the unimaginable pain of losing their child to a vaccine-preventable disease.

“This new data shows why we need to redouble our efforts to find communities being left behind, whether they be in urban slums, remote areas or conflict settings.”

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security

Yahoo News

Yahoo News