Be Here Now: Why this year is the perfect time for an Oasis reunion

The 1975 have some things to say about 1995, as well. “Get back together, stop messing around,” singer Matty Healy advised Oasis in a recent Canadian radio interview. “Can you imagine being in potentially – right now, still – the coolest band in the world, and not doing it because you’re in a mard with your brother?” he argued. “Grow up, headline Glastonbury, have a good time.”

Indeed, at no point since their acrimonious 2009 split has the time been so perfect for an Oasis reunion. You see, Britpop has become a form of generational wonderwarfare. The most highly evolved Gen Zers have developed a reflex howl of “OK Boomer!”, triggered whenever the older generations – misty-eyed behind their Lennon shades, and testing the seams of their vintage Fred Perry shirts – start banging on about the Nineties as a golden age of British pop culture. Force the average 2020s teenager to yet again hear about Sunday’s NME stage line-up at Glastonbury 1994 – Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Radiohead, and Echobelly! – and they might roll their eyes clean out of their heads.

If Britpop gets endlessly lauded as a champagne supernova of good times, it’s only because so many of us can say we were there. The sad truth is, Britain has a long and frustrating history of missing out on its own pop culture revolutions. The stadium excesses of Beatlemania mostly took place in America. For Beatles fans in Britain – where, beyond their theatre tours, the band played only one 15-minute arena gig at Wembley Pool for the 1966 NME Poll Winners’ Party – they were a largely televised phenomenon. The various late-Sixties summers of love were American affairs too, taking over Haight-Ashbury and Woodstock. In the UK, you had to have been a very early Pink Floyd fan, one of the 40 or so groovers in the studio for The Beatles’ “All You Need is Love” satellite broadcast, or a Kensington trust funder letting Jimi Hendrix crash on your sofa to say you’d really “lived” the Age of Aquarius.

Bowie killed Ziggy in front of just 5,000 star-children at the Hammersmith Odeon in 1973. Punk played out, all too briefly, in a handful of gob-smattered clubs and King’s Road boutiques. No one who was seriously involved in the rave and acid house explosion of the late-Eighties can remember a second of it, let alone stick a pin in a map to show you where it occurred. The UK’s arena circuit remained so underdeveloped well into the Seventies that even rock giants such as Led Zeppelin were playing regional theatres right up to their legendary Knebworth show in 1979. In fact, before The Stone Roses convened the Madchester faithful at Spike Island in 1990, mass British pop-culture communions were as rare as an honest government appraisal of Brexit.

But during Britpop, they were legion. Blur at Alexandra Palace in 1994, then Mile End Stadium the following year. Oasis at Maine Road and Knebworth. With support slots crammed with like-minded breakthrough indie acts – Supergrass, The Boo Radleys, The Charlatans, Manic Street Preachers, Cast – these shows weren’t just one-band gigs. They were snapshots of an era. Major UK festivals like Glastonbury and Reading dedicated entire days to Britpop bands. Pulp virtually stole the decade when they replaced The Stone Roses as Glastonbury 1995 headliners at the last minute. And all of it was splashed across a plethora of Nineties youth culture TV shows, newspapers, and a growing festival scene. Britpop was arguably the first UK-bred music movement that millions of UK-bred music lovers truly felt a part of.

And can again. This year offers a unique chance for a generation of pop fans to experience 1995 for themselves, pretty much as-was. In a rare break from Damon Albarn’s Gorillaz activity and bassist Alex James’s cheese business, Blur return to Wembley in July. That same month, Pulp will play Finsbury Park as part of a major UK tour. Hit both gigs and you can claim to be a reborn child of Britpop, even if you’re young enough to think Lush is a cosmetics shop, and the words “Chris Evans” bring to mind Captain America, as opposed to Shaun Ryder delivering some Olympic-level swearing on teatime TV. For one glorious summer we can pretend rent is affordable again, there’s only been a mere 30 years of (male team) World Cup hurt, and there’s no such thing as James Corden.

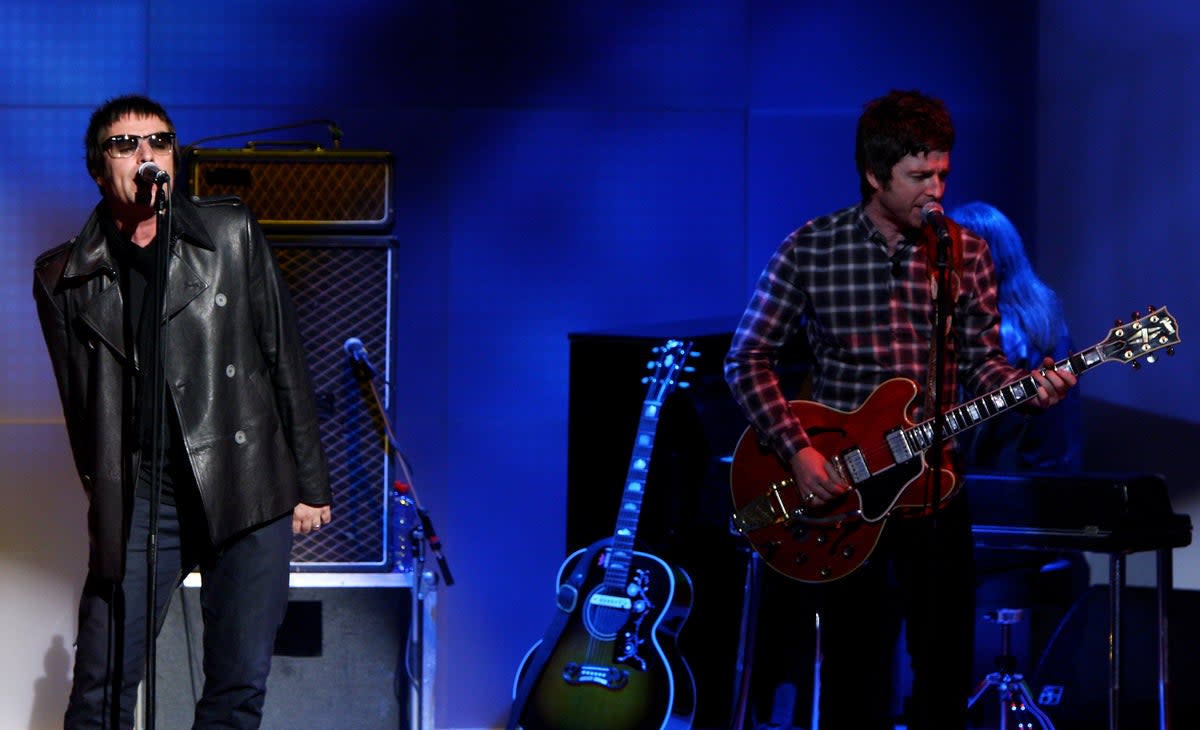

Except, of course, one key piece of the 1995 puzzle is missing. The 14-year-long, will-they-won’t-they saga of the Oasis reunion has, like so many equally dramatic soap storylines that dragged on too long, become tedious in the extreme. Throughout his wilderness years, Liam Gallagher regularly took to Twitter to beg, badger and bravado his brother Noel into reforming their Britpop behemoth. His pleas fell on deaf ears, however, as the elder Gallagher’s solo career took wing with his High Flying Birds band. Once Liam’s solo career also gained traction, he no longer needed Oasis; the odds of a reunion plummeted further. But he still claims to be “Oasis ’til I die” on Twitter, and amid a recent divorce – so often the catalyst for high-profile band reunions by artists who previously said they’d rather gnaw their own foot off than play together again – Noel has opened the door a crack. “You should never say never,” he told BBC Radio Manchester last month. Although, he said, “it would have to take an extraordinary set of circumstances”.

Would a once-in-a-lifetime alignment of the Nineties indie rock planets suffice, Noel? The fact is, there has never been, and never again will be, a better time for Oasis to reform. Not for the music as such. Any given year, the dedicated fan can see Liam and Noel perform Oasis’s greatest hits separately, with occasional added Bonehead. Nor does anyone feel their life remains incomplete until they’ve witnessed the triumphant return of bassist Paul “Guigsy” McGuigan to a major international stage.

But this year and this year only, an Oasis reunion wouldn’t smack of nostalgia cash-in but represent a coming together for the ages. As part of an impromptu national celebration of Britpop, a 2023 Oasis reunion would be a monumental moment; an erasure of long-engrained generational divides and a modern cultural closure. While we can’t expect Blur, Oasis and Pulp to agree on a running order to recreate Glastonbury 1994, a Liam-Noel reunion would at least give Gen Z their own Blur vs Oasis moment. Today’s teenagers could finally experience the thrill of the hallowed Nineties for themselves – with its old-school tribal rivalries, its factional uniforms and its ubiquitous Phil Daniels – before coming to the conclusion, as most of us did, that Pulp’s Different Class was the best Britpop record, anyway. This year is going supersonic with or without Oasis. Maybe, helped by Healy, Liam and Noel will wake up and smell the cocaine cornflakes.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News