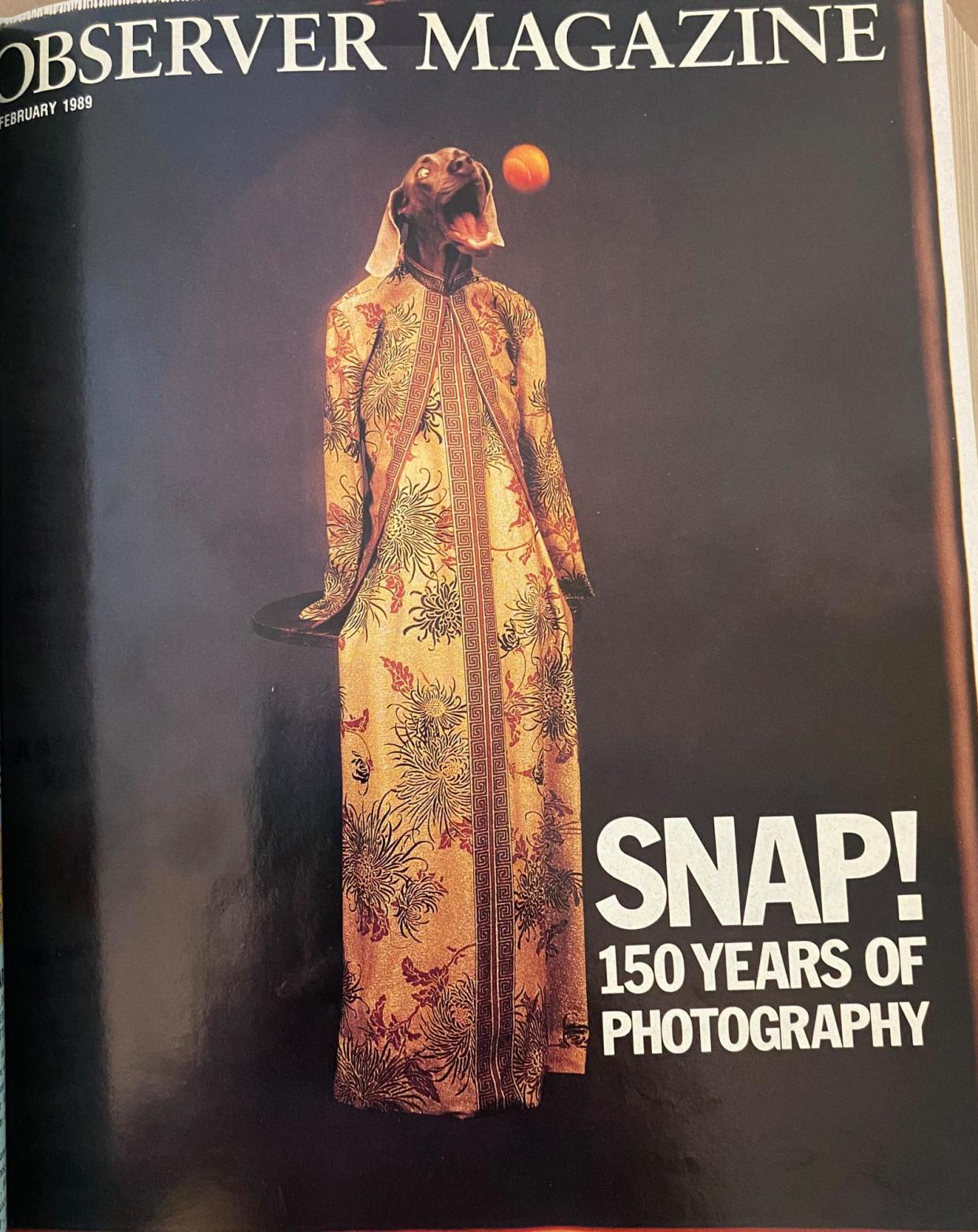

‘Painting is dead’: celebrating the 150th anniversary of photography in 1989

‘From today painting is dead!’ was how French artist Paul Delaroche greeted, horrified, one of the earliest photographs. It wasn’t, but celebrating photography’s 150th anniversary in 1989, the Observer explored how this ‘miraculous new invention’ changed our ways of seeing.

Cartes de visite – among the earliest affordable mass imagery – challenge the cliché of Victorian photography. Rather than a bewhiskered paterfamilias in his Sunday best, rigid and unsmiling as required by long exposures, they display surprising diversity and a taste for sensation. Alexandra, Princess of Wales, gives her daughter a piggyback; a bare-bottomed boy gets smacked; there are giants, severed heads, bearded children, chimney sweeps and celebrities.

Most captivating are candid early shots of ‘ordinary folk’ at work and especially at play

Another feature explored the visual trickery of Victorian ‘spirit’ photography – ghosts, ghouls, wraiths and spectral presences. Apparitions were conjured with simple techniques including multiple exposure, montage and double printing. This ‘paraphernalia of deception’shifted gradually from swindler’s trick to innocent family entertainment before making itself at home in advertising, art and the nascent film industry.

Most captivating are candid shots of ‘ordinary folk’ by Paul Martin, a 19th-century Martin Parr who used lighter, less cumbersome equipment to capture people at work and especially at play. Pictures of men and women napping, bathing and cuddling on Yarmouth beach defied the disapproval of an 1898 photographic journal, which berated ‘Hand-camera fiends who snap-shot ladies as they emerge from their morning dip.’

The special edition closed with legendary Observer photographer Jane Bown’s ‘Room of My Own’. Her farmhouse drawing room was full of animals – ceramic, sculpted, painted and a real dozing Labrador – but contained only two photographs: one of her daughter and one of the formidable Observer former picture editor, Mechthild Nawiasky, who hired Bown. Having fallen into photography at the end of the war (she enrolled on a photographic course, she explained, because ‘it didn’t seem boring’), Bown was wonderfully understated about her gifts: ‘There’s not really anything to say, I stick my camera up and I take a picture.’

Yahoo News

Yahoo News