The 'perfect environment': how FGM is set to surge during the pandemic

Faith* clambered through the forest after her friends, desperate to escape the cloud of stigma that had engulfed her for months.

All the other girls they knew had undergone female genital mutilation (FGM), or cutting, explains Faith. “We felt left out. They called us names and avoided us. They saw us only as children.”

So in an attempt to gain acceptance, the six girls traipsed for two hours through the pine and cypress trees to a meeting point near their village in West Pokot County, some 220 miles northwest of Nairobi, Kenya's capital.

“We met the cutter in the forest and had the procedure in turns,” Faith says. “We went one at a time; I wasn't scared until it was my turn.

“Peer pressure gives you the courage to endure pain,” the 14-year-old adds. “I had been determined not to have FGM. But I gave in when the pressure became unbearable.”

FGM has been illegal in Kenya for almost a decade. But Faith says this did not deter them - the girls thought the police and the government were “too busy” with the coronavirus pandemic to come to their village and stop them.

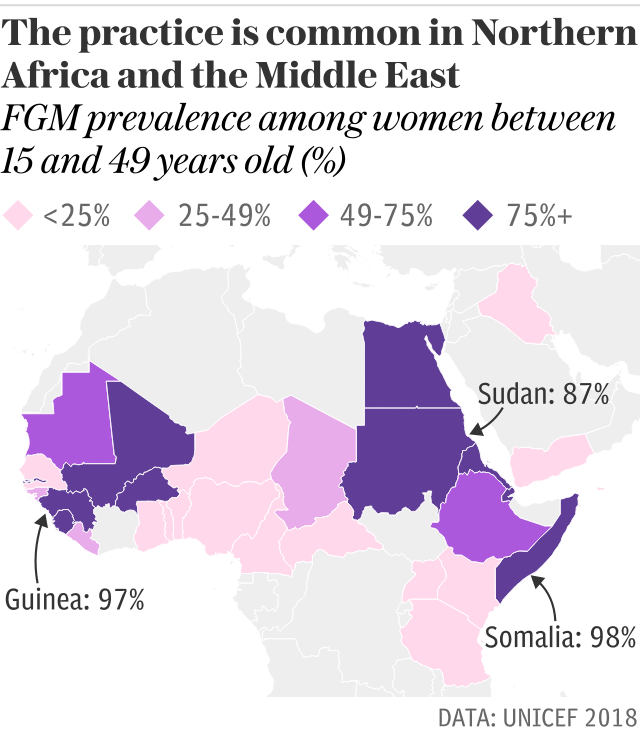

For centuries, girls have been forced by family members or cultural norms to undergo various forms of FGM, a non-medical practice where the genitals are cut. An estimated 200 million women and girls alive today have undergone the procedure.

Over the last three decades, significant progress has been made to stop FGM but now health workers and activists say that coronavirus lockdowns and school closures have triggered a resurgence of cutting in parts of Africa.

“Covid has given the perfect opportunity and the perfect environment for FGM to come back in full swing,” says Domtila Chesang, an activist who has been working to end the practice in West Pokot for a decade.

Ms Chesang estimates there were fewer than a dozen reports of FGM in her county from March to June last year. But since the schools closed to stop the spread of the virus in March, she has been “overwhelmed” by a staggering number of reports.

Local police support her claim; they say that some 500 girls have been cut in this region alone since March.

“Life has been turned upside down and people are turning back to old beliefs, while prolonged holidays means that cutting can take place without people noticing,” Ms Chesang says.

As uncertainty and the global economic downturn continues, she fears numbers will rise even further. To make matters worse, the Kenyan government has said that schools would not open until 2021.

“As soon as one person is cut in a community, expectation and pressure spreads like wildfire,” Ms Chesang adds.

Health workers say they are seeing similar trends emerging in at least six different regions in central, western and northern Kenya.

In Kuria East, near Lake Victoria, some community elders have reportedly blamed Covid-19 on a failure to uphold traditions like female circumcision that are believed to appease the gods. In the Loita region, south of Nairobi, families in dire economic straits are cutting their daughters to get a higher “bride price”.

The resurgence is not confined to Kenya. Activists have reported similar trends in several other African countries, including Nigeria and Tanzania.

In Somalia, where around 98 per cent of girls aged between five and 11 have been cut, the girl's rights NGO Plan International has warned that a strict lockdown has led to a spike in incidents. Cutters who have fallen on hard times are reportedly going from house to house in the Somali capital Mogadishu offering to cut girls stuck at home.

“We’re very concerned about these girls’ futures,” says Rose Caldwell, chief executive of Plan. “Education is a vital lifeline for girls and young women across the world and we must not allow this to be lost as another casualty of this crisis.”

There is precedent for this. At the height of the West Africa Ebola outbreak between 2013 and 2016, five million children were out of school - research has found that a large proportion of girls, in particular, never returned.

And according to a recent survey by the charity Room to Read, 49 per cent of girls in low-income communities say they are unlikely to go back to the classroom after the pandemic due to financial struggles, instead turning to early marriages.

Delays in anti-FGM programmes due to the pandemic also mean that two million girls who would otherwise be safe from the practice could be at risk over the next decade, according to the UNFPA, the United Nation's reproductive health agency.

“Covid-19 response measures have exacerbated many of the drivers of female genital cutting, such as social isolation, school closures, lack of law enforcement, and food insecurity due to loss of livelihoods,” says Ebony Riddell Bamber from the Orchid Project, a UK-based charity.

“On a global level, the pandemic could have a devastating impact on the progress we've made to end the practice,” she adds.

*We have changed Faith's name in this report

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security

Yahoo News

Yahoo News