How pioneering Mediapart has set the French news agenda

It began with a handful of journalists disillusioned with the state of the country’s established media, a hefty bank loan and an even larger injection of optimism.

Ten years on, the French investigative website Mediapart has become a thorn in the side of politicians, public figures and those with something to hide.

In the past decade, the site, which claims no particular political affiliation, has led the news agenda, breaking some of France’s biggest scandals involving politicians across the ideological spectrum.

Its investigative teams dig with a dog-with-a-bone tenacity for as long as it takes, and if, in the beginning, its high-profile targets were tempted to deny its accusations and denigrate its journalists, most think twice these days before shooting the Mediapart messenger.

The website also makes money. Lots of it, despite having no advertising, no public subsidies and no wealthy patrons, being entirely financed by reader subscriptions (currently €110 a year, €50 for students, pensioners and the unemployed or those on low incomes).

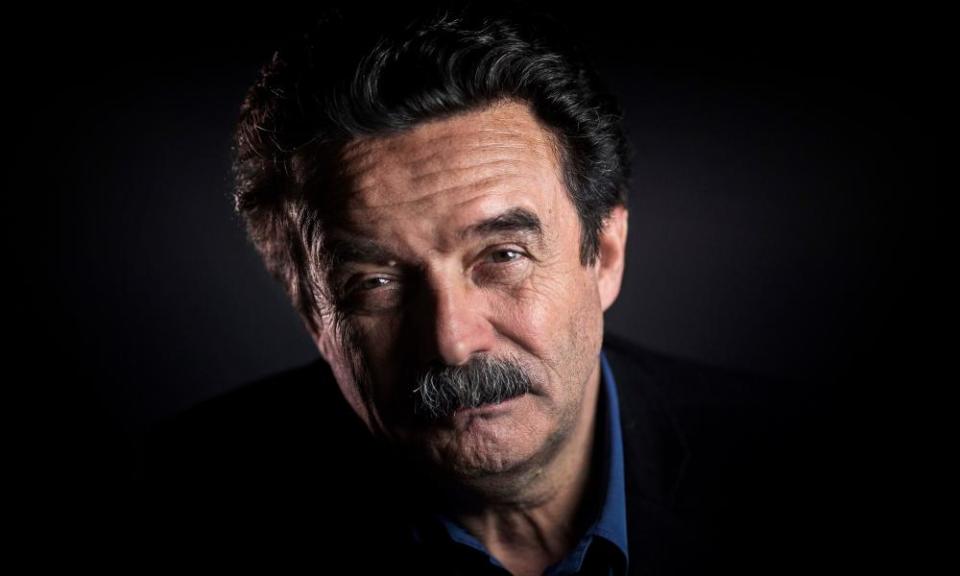

“Mediapart is unique,” says Edwy Plenel, Mediapart’s editorial director and co-founder. He points to a poster on the wall of the website’s conference room. The slogan reads: “Mediapart: only our readers can buy us.”

When it started in 2008, the website had 25 staff. It now has 80, including a US correspondent, an English-language site, a free “Club” that runs parallel to the main site with blogs and commentaries and is branching out into live video blogs and television.

“When we started, we had no idea where it was going or if it would succeed. It cost us all money but this was a condition of our success. I took out a loan because we felt it was essential to pay decent salaries for three years,” Plenel told the Anglo-American Press Association.

“We told people who came to work for us that we couldn’t guarantee a job for life but we could guarantee them an adventure and correct pay for at least three years. Within two and a half years we had broken even.”

Today, the loans have been paid off and Mediapart has €6.5m in the bank. Last year’s turnover was €13m, with a net profit of €2.4m. It has 140,000 subscribers and 2-3m unique visitors a month.

Plenel says financial independence is key to a free and independent press. “If a newspaper is owned by an industrialist, then you can have the best quality team you want but you won’t be able to touch the interests of that industrialist. This affects what you do and means you have a tendency to abstain from being audacious,” he says.

“We know the best guarantee of our independence is financial success. Journalists must have access to capital to safeguard their independence.”

He adds: “Not having advertising, not having public subsidies means we are totally independent and we can control and guarantee that independence.”

Looking back on the last decade as Mediapart prepares to celebrate its 10th birthday this weekend, there is one affair that marked a turning point for the website.

In December 2012, Mediapart accusing the newly appointed Socialist budget minister, Jérôme Cahuzac, whose job was to stamp out tax fraud, of having had a non-declared bank account in Switzerland. Cahuzac counter-accused Mediapart of “serious, defamatory lies” and took to the floor of the Assemblée Nationale telling French MPs: “I have never had an account in Switzerland or anywhere else abroad.”

Mediapart kept digging and publishing as Cahuzac kept denying. In March 2013, he resigned from the government to clear his name, still accusing Mediapart of defamation.

A month later Cahuzac admitted the accusations and was charged with tax fraud. It took until December 2016 for the case to go to court and he was given a three-year jail sentence, upheld by an appeal court last month.

For Fabrice Arfi, the journalist who led the Cahuzac investigation and was accused of lies, slander and the worst of journalism, it was a relief tinged with the realisation it could have gone either way, despite the evidence and documentation his team had gathered.

“What was disturbing was how the lies became accepted as the truth and the truth was considered lies,” Arfi said afterwards.

Another headline-grabbing investigation resulted in claims – vigorously denied – that the Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi had financed Nicolas Sarkozy’s 2007 election campaign to the tune of €50m, which is still under investigation.

Mediapart also obtained secret tapes made by the butler of the late L’Oréal heiress Liliane Bettencourt suggesting high-level corruption and that France’s richest woman was being despoiled of her wealth by members of her entourage, some of whom were later convicted.

“Before Mediapart was created there was a lack of investigative journalism and a lot of what I call passive journalism. It’s useful in the media ecosystem to have a journal that investigates and is independent. It gives courage to the whole profession,” Plenel says.

Plenel added: “Our work is constantly under attack from political and economic powers who don’t want us to challenge their influence. Not only is the truth in danger, but freedom of truth is in danger and that’s why we have to keep promoting independent journalism and defending the right of the public to know.

“It’s about journalism being at the service of people and the public good. At Mediapart we’ve conquered the first hurdle – we’ve succeeded. Now it’s about continuing the work.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News