Plaster-like vaccine patches may one day replace measles and rubella jabs, research shows

A plaster-like vaccine patch could be a safe and effective alternative to injected measles and rubella immunisations, new research shows.

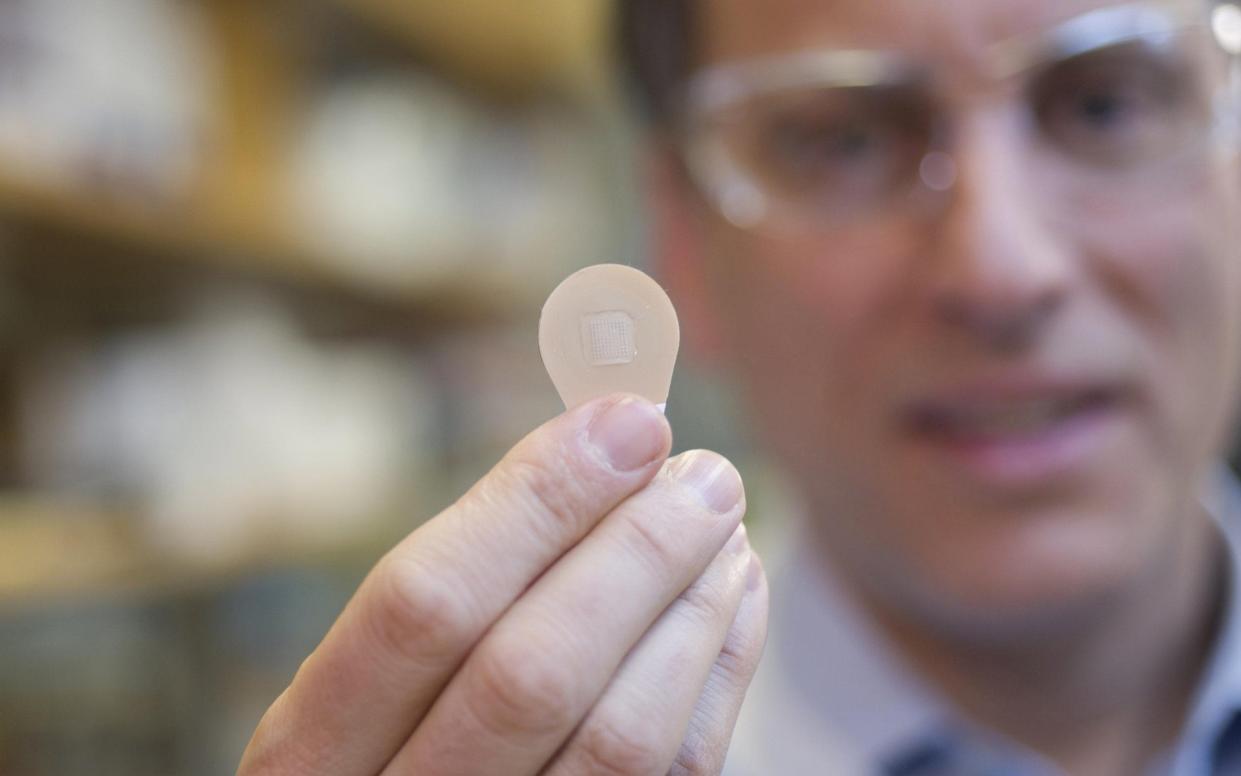

‘Microarray patches’ are small plaster-like devices packed with microscopic needles that lightly puncture the skin. There are mounting hopes that they will be the future of vaccine campaigns.

Not only are they pain-free and easier for people who fear injections, but they are also easier to transport and store than traditional vaccines because they do not require refrigeration.

There are other benefits, too; people with minimal training can administer them, rather than doctors and nurses, and the risk of ‘needlestick’ injuries is reduced. Contaminated needles are still responsible for spreading diseases like HIV and hepatitis.

The latest study, previously outlined at a conference in Seattle but now published in the Lancet, is the first to assess whether childhood killers measles and rubella could be delivered via the patches.

Led by researchers in the Gambia, the trial gave 45 healthy adults, 120 toddlers and 120 babies the same measles and rubella vaccine, either through a microarray patch or a conventional injection.

It found that the immune response was the same through both routes. After one dose – delivered by a patch held in place for five minutes – just over 90 per cent of babies were protected.

A ‘sensation’, but no pain

The trial – led by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) and US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – also found no safety concerns.

“Although it’s early days, these are extremely promising results which have generated a lot of excitement,” said Professor Ed Clarke, a paediatrician at the Medical Research Council Unit, a section of LSHTM based in The Gambia and co-author of the report.

“They demonstrate for the first time that vaccines can be safely and effectively given to babies and young children using microarray patch technology. Measles vaccines are the highest priority for delivery using this approach but the delivery of other vaccines using microarray patches is also now realistic. Watch this space.”

Speaking to the Telegraph, he added that there is a “sensation” but no pain associated with the vaccine patches.

But the technology is still some years away; even at an accelerated pace, it could take three to four years to go through late-stage trials, licensure and roll-out.

Still, the researchers hope that the new immunisation technology could be used to help stem huge gaps in global vaccine coverage. In 2022, only 83 per cent of children had been given at least one dose of a measles shot by their first birthday, which, according to the World Health Organisation, is the lowest rate since 2008.

The result has seen a surge in measles, with reported cases jumping to 321,582 in 2028 – nearly double the 171,153 recorded in 2022.

The UK, too, has been struggling with the highly infectious childhood killer, with almost 900 cases recorded already this year, far outstripping the total of 368 cases detected in all of 2023.

“The positive results from this study are quite gratifying to us as a team,” said Dr Ikechukwu Adigweme, from MRC Unit The Gambia and co-author of the report. “We hope this is an important step in the march towards greater vaccine equity among disadvantaged populations.”

Prof Clarke said the final product is likely to have a “similar cost” as traditional vaccines. But if you take into account “cold chain [requirements] ... disposal of needles,needle-stick injuries and the risk of blood borne infections like hepatitis B and HIV … the patches could be cheaper overall.”

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security

Yahoo News

Yahoo News