Prescription of opioid drugs continues to rise in England

The prescription of opioid drugs by GPs in England is steadily rising, especially in more deprived communities, even though they are potentially dangerous and do not work for chronic pain, a new study reveals.

The study shines an alarming new light on the legal use of opioids in England; potentially inappropriate yet sanctioned by doctors. It also reveals a north-south divide. Nine out of 10 of the highest-prescribing regions were in the north. Prescriptions of painkillers were higher in areas of socio-economic deprivation.

Opioids have hit the headlines mainly because of their abuse in the United States. The authors of the study in the British Journal of General Practice, which uses official government data, say opioids are rightly given to people to cope with cancer pain and short-lived acute pain. But as the authors also point out, the widespread prescribing of opioids for people with long-term pain is controversial because “opioids are ineffective in much chronic pain beyond modest effects in the short term”.

Almost 100 people are dying every day across America from opioid overdoses – more than car crashes and shootings combined. The majority of these fatalities reveal widespread addiction to powerful prescription painkillers. The crisis unfolded in the mid-90s when the US pharmaceutical industry began marketing legal narcotics, particularly OxyContin, to treat everyday pain. This slow-release opioid was vigorously promoted to doctors and, amid lax regulation and slick sales tactics, people were assured it was safe. But the drug was akin to luxury morphine, doled out like super aspirin, and highly addictive. What resulted was a commercial triumph and a public health tragedy. Belated efforts to rein in distribution fueled a resurgence of heroin and the emergence of a deadly, black market version of the synthetic opioid fentanyl. The crisis is so deep because it affects all races, regions and incomes

They are also potentially dangerous. Luke Mordecai, a pain research fellow at University College London Hospital and the lead author of the study, is calling for a register of all those who are taking the equivalent of more than 120mg of morphine a day. “There should be a national database to keep track of these people,” he said. “There is very high morbidity and mortality [among them], a lot of it avoidable.”

The gold standard, he said, was treatment by a multi-disciplinary team of pain experts, including a specialist consultant, nurse, psychologist and physiotherapist. Yet that is rare: only 40% of pain consultants provide it. Many people could come off opioids altogether with the best care.

Chronic pain is very common. As many as one in seven people have complained of moderate to severely disabling pain and the numbers rise with age. Opioids do not work, but, says the study, many GPs prescribe them because they think it is unethical to refuse their patients painkillers.

The study looks at the total amount prescribed in grams of each of eight common opioid drugs and finds a rise in six of them. Mordecai talked of “a steady increase” but declined to quantify it in percentage terms because of the relatively short time period.

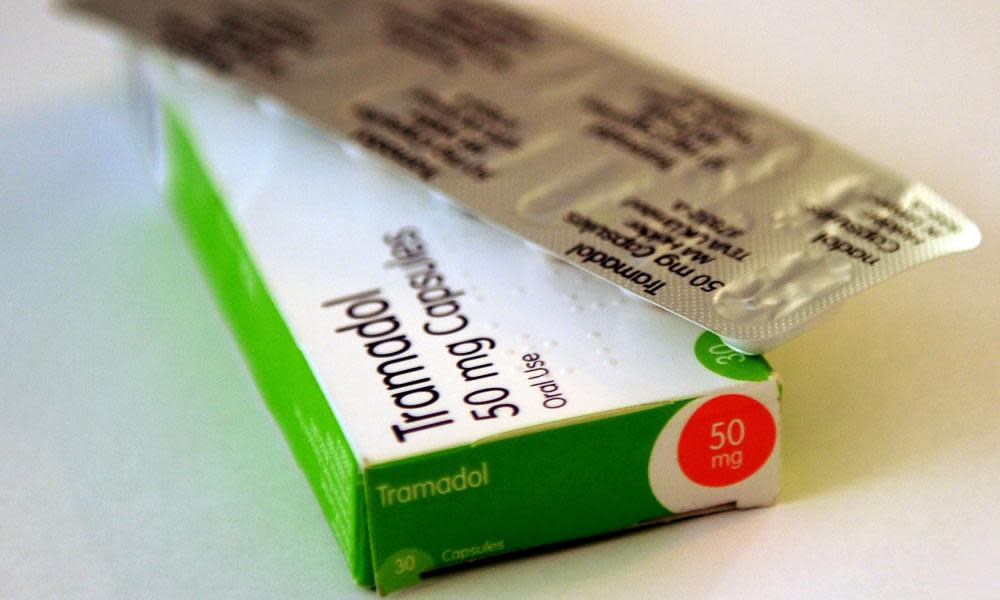

The most prescribed opioid drug in England over the 43 months of the study, from August 2010 to February 2014, was tramadol. It is stronger than over-the-counter codeine but does not have the stigma of the powerful morphine.

“It is not seen as a strong opiate although actually I think it really is,” said Mordecai. “It is the first port of call for troublesome pain but it can become quite addictive.”

Tramadol is implicated in a rising number of deaths due to drug misuse – in Northern Ireland up from 9% to 40% in 2011. In England it was found responsible for 132 deaths in 2010 but 240 in 2014. In that year, it was reclassified as schedule 3 and prescription was limited to one month’s supply at a time. But, the study’s authors note, that failed to work with codeine in Australia. Prescriptions of buprenorphine, oxycodone, codeine and morphine also rose, the study finds. There was a small rise in fentanyl prescription, while prescribing of methadone and dihydrocodeine dropped.

Mordecai said more studies would be needed to find out why prescriptions were highest in more deprived areas and in the north. “We know that chronic pain affects more people of low socio-economic status,” he said. The paper notes that an association has also been found between unemployment and poor outcomes in chronic pain.

“It is something that needs a great deal more work. People of higher socio-economic status might have access to better facilities and ask more questions or want the best treatment possible,” he said.

“This study exposes increasing rates of prescription of a class of drugs whose use for chronic pain is controversial, with potential for abuse, and an association with serious adverse effects and premature death,” concludes the paper. “The authors call on policymakers to identify the reasons for this variation to enable avoidable harm to be addressed.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News