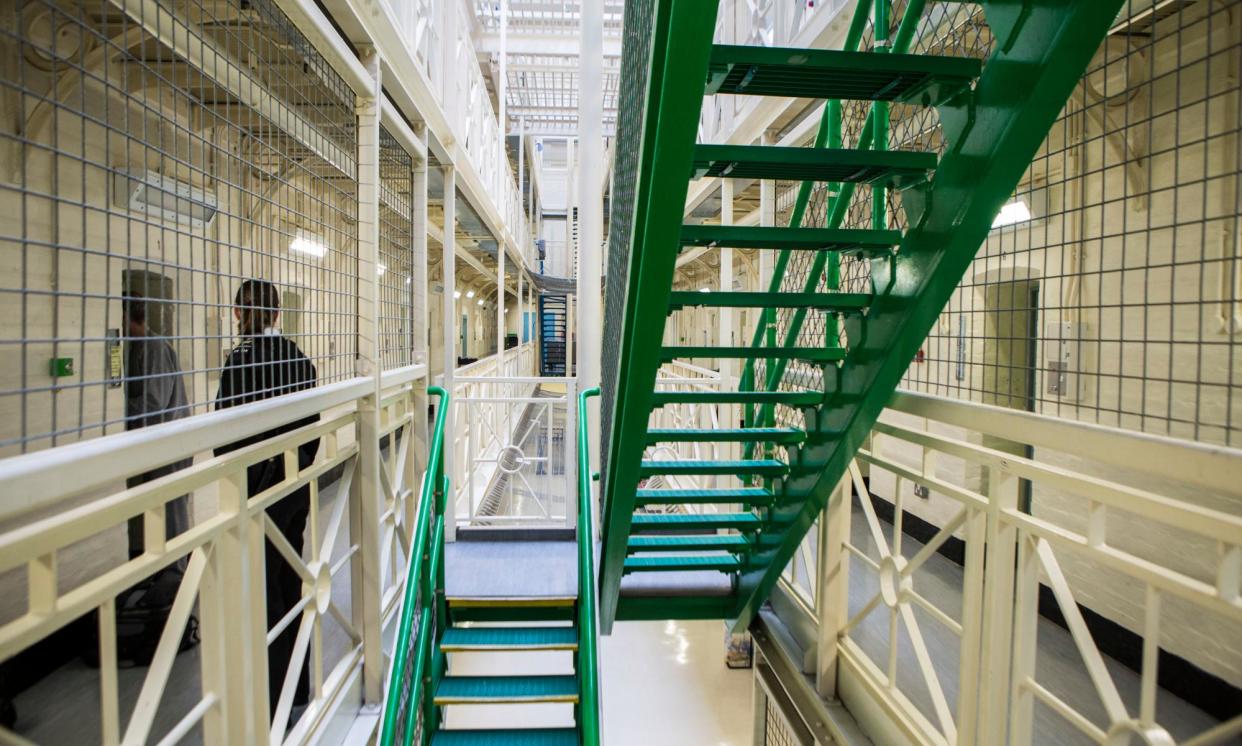

Prisons ‘sleepwalking into crisis’ as inmates forced to share single cells

The scale of the prison overcrowding crisis has been laid bare by figures revealing that a quarter of prisoners in England and Wales have been sharing cells designed for one person with at least one other inmate.

According to the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), 11,018 cells intended for single use were being shared by two prisoners, with a further 18 such cells shared by three inmates. The overall prison population – which has ballooned over recent decades because of longer sentences and court backlogs – stood at about 88,000 when the statistics were originally compiled in late February.

Steve Gillan, the head of the Prison Officers Association, said sharing cells designed for one person creates tension among inmates, making the jobs of overworked prison staff even more difficult: “It is no wonder that the prison service is struggling to retain prison officers and operational support grades in England and Wales. The pressure on staff is intolerable and dangerous.”

He warned that the government was “sleepwalking into another crisis” after it “learned nothing” from the landmark Woolf report into the 1990 Strangeways riots, in which two people died. Among the report’s recommendations was that no prison should hold more inmates than is provided for in its certified accommodation level – which represents the “good, decent standard of accommodation” that the Prison Service says it aspires to provide to all inmates.

But three in five prisons are now overcrowded, with the problem most acute in inner-city Victorian reception jails such as Leeds, Bristol and Bedford, according to Charlie Taylor, the chief inspector of prisons.

Taylor said a lot of maintenance work is deferred in order to keep cells in use, and that too many prisoners have poor access to education and employment – activities that can reduce the chance of reoffending on release.

He believes that sharing is not inherently problematic, and can be a “protective factor against self-harm”, but is critical of the length of time many inmates are continuing to be confined in their cells, as they were during the pandemic. “The key issue is the conditions in which people are sharing cells,” Taylor said. “If prisoners were out of their cells spending the majority of their day in education and employment, then cramped conditions, while not ideal, would be less concerning. But the reality in many jails is two men spending up to 23 hours a day penned into a very small cell that was designed for one person, often in a poor state of repair and with an unscreened toilet. When you consider that, it is hardly surprising that levels of violence are rising and that we are seeing a worrying rise in the use of drugs,” said Taylor.

Prison Service rules require that cells are only shared where a prison group director has assessed them to be of an adequate size, condition and safety. Risk assessments are carried out on prisoners before deciding whether it is safe for them to share cells in closed conditions. Even a small oversight can lead to a vulnerable inmate being trapped with a potentially violent prisoner.

“We do complete risk assessments in custody but sadly on occasions there are times where people don’t get on. We would identify vulnerability, and those people get marked up to a single cell,” Mark Icke, the vice-president of the Prison Governors’ Association, said.

With many prisons at breaking point, the government has adopted emergency measures, including allowing some offenders to be released early, to try to tackle the overcrowding crisis. But the prison population is still projected to increase to between 94,600 and 114,800 by March 2028, in part because of a growth in police charging and changes in policy to keep the most serious offenders locked up for longer.

Andrea Coomber KC, chief executive of the Howard League for Penal Reform charity, said sentencing reform is vital to create a more humane and sustainable justice system. “The government needs to take a serious look at other options and fundamentally reconsider sentencing regimes, which have meant sentences have gotten longer and longer over the last 20 years,” she said. “Nearly 40% of prisoners are there for non-violent offences. As a starting point, we need to think if any of those people need to be in prison at all.”

An MoJ spokesperson said: “We are delivering the biggest prison expansion since the Victorian era – including two prisons in two years – to help rehabilitate offenders and keep our streets safe. We will always ensure there is enough capacity to serve the outcome of the courts and keep dangerous offenders behind bars, and cells are only doubled up where it is safe to do so.

“Our sentencing bill will help reduce reoffending through greater use of tougher community sentences.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News