Raising the curtain: 15 Black, queer game-changers who made a mark on British culture

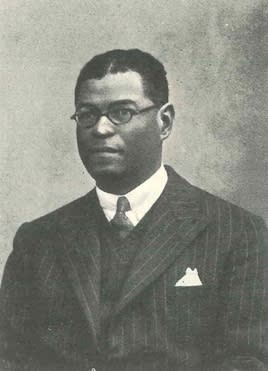

John Payne (1872-1952)

This American singer and choirmaster settled in London in 1919 and acquired a home there on Regent’s Park Road. This became a popular meeting place for African-American expatriates and visitors, mainly from the world of music.

Artistes such as Paul Robeson and Adelaide Hall, who came here in the 1920s and 1930s, found their way to Payne’s home, if not for a place to stay, then for introductions to new friends in the entertainment and social circles of England. At the start of the Second World War in 1939, Payne left London and made a new home for himself in Looe, Cornwall.

There he became a popular figure in the local community, teaching music, singing in choirs and organising concerts for the troops. He was buried in West Looe cemetery, where his memorial reads: “Singer and musician. Loved and remembered by his many friends. The song is ended, but the memory lingers on.”

Claude McKay (1889-1948)

The bisexual Jamaican poet travelled extensively, but couldn’t settle in Britain for very long. When he lived in London from 1919 to 1921, he was critical of British colonialism, disliked the climate and found English whites “a strangely unsympathetic people, as coldly chilling as their English fog”.

On the positive side, McKay found employment on the radical weekly newspaper, Workers’ Dreadnought, edited by the suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst. He has been described as the first Black socialist to write for a British journal. In the 1920s, McKay became one of the most celebrated poets of the Harlem Renaissance.

Lawrence Brown (1893-1972)

This American composer, arranger and pianist made London his home in the 1920s and possibly had a brief relationship with the English composer Roger Quilter. In 1922, while staying at the home of John Payne, Brown was introduced to Paul Robeson, who began singing Brown’s arrangements of spirituals.

Robeson went on to become one of the most famous singers of his time and his successful professional association with Brown, which began in 1925, lasted into the 1960s. Musically, Brown was Robeson’s most important collaborator. In 1958, when Robeson was a guest on BBC Radio’s Desert Island Discs, he paid tribute to Brown by including one of their many recordings, the spiritual Steal Away.

Dr Cecil Belfield Clarke (1894-1970)

Cecil came to the UK from Barbados and practised as a family GP at 112 Newington Causeway, near Elephant and Castle in south London, for 45 years. In 1931, he was a founder member of the League of Coloured Peoples, which was one of the first Black-led organisations in Britain.

During the London Blitz of 1940/41, in spite of intensive bombing of Elephant and Castle, Clarke travelled daily to his surgery from his home, Belfield House in New Barnet. For many years, he lived there with his partner, Edward ‘Pat’ Walter.

Alberta Hunter (1895-1984)

A popular American blues singer in the 1920s, Hunter sang mostly about anguished love affairs, which had a special resonance for queer audiences. Women like Hunter and Josephine Baker found that Europe offered more possibilities for work and acclaim, and they captured the continent with their songs and elegance. In 1930, Hunter sang at London’s Dorchester Hotel, where her admirers included Noel Coward, Cole Porter and the Prince of Wales (later the Duke of Windsor).

She recorded Coward’s I Travel Alone and Porter’s Miss Otis Regrets in London in 1934. Hunter returned to the USA in 1939 and, in the 1950s, she gave up showbusiness to begin a new career as a nurse. After retiring from the nursing profession in 1977, Hunter resumed her singing career and became a sensation in New York at a Greenwich Village club called The Cookery.

Leslie ‘Hutch’ Hutchinson (1900-1969)

The popular bisexual cabaret entertainer came to Britain from the Caribbean island of Grenada in the 1920s and was ‘adopted’ by the rich and famous. Cole Porter, the famous gay songwriter, became his friend and musical alter ego. Hutch was the best-known interpreter of Porter’s songs.

In 1920s and 1930s London, Hutch entertained in swanky nightclubs such as the Cafe de Paris, but he was equally loved by the ordinary British public. His sexual exploits with men and women were legendary. After the Second World War, as the rock’n’roll era began, his sophisticated performing style fell out of fashion. When he died his obituary in The Times deemed him “the ideal artist for the relaxed hour after dinner”.

Granville ‘Chick’ Alexander (1905-1969)

Chick was a Jamaican dancer who also worked as an artist’s model. In the Second World War, during the Blitz, Chick volunteered as a stretcher bearer during air raids on London His wartime West End stage appearances included Cole Porter’s musical, Panama Hattie.

Reginald Foresythe (1907-1958)

Born in London to an English mother and a father from Sierra Leone, Foresythe was a pianist, bandleader and composer as well as a jazz innovator. Public school-educated, he spoke with an upper-class accent and won respect for his bold and dazzling compositions in the 1930s world of jazz. These included Dodging a Divorcee, Greener the Grass and Serenade for a Wealthy Widow.

In the USA, Foresythe was admired by such jazz legends as Louis Armstrong and Fats Waller. He also worked as an accompanist for his friend, the cabaret singer Elisabeth Welch. She described Foresythe as a, “Sweet, simple, charming person. His appearance was always immaculate and elegant. We all loved him. I know he had liaisons with men, but they were always very discreet.”

During the Second World War, Foresythe served in the RAF, but, after the war, alcoholism destroyed his health and his career went into decline.

Jimmie Daniels (1908-1984)

An American cabaret entertainer who toured Europe in the 1930s, Daniels appeared in such popular London nightclubs as Ciro’s with the composer and bandleader Reginald Foresythe. Daniels’ lovers included the Scottish film-maker Kenneth Macpherson.

Garland Wilson (1909-1954)

American jazz pianist best known for joining the singer Nina Mae McKinney on her European tour of 1932. Wilson worked extensively in Britain in the 1930s.

Ivor Cummings OBE (1913-1992)

Born in West Hartlepool, Cummings’ father was a doctor from Sierra Leone while his mother was English. After joining the Civil Service, Cummings worked for the Colonial Office in Whitehall. During the Second World War he was one of the most important and influential Black men in Britain.

Cummings would assist any Black person who approached him for help. For example, in 1941 he visited the East End of London to investigate complaints about racism he had received from the representative of a group of African and Caribbean merchant seamen and workers.

In 1948, when Cummings was at Tilbury Docks to meet the passengers of the Empire Windrush, he addressed the newcomers from the Caribbean in a tone of patronising kindliness which exactly echoed the spirit of the time. An elegant gentleman, who chain-smoked with a long cigarette holder, he was once likened to Noel Coward.

Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson (1914-1941)

A popular Guyanese bandleader in 1930s Britain, Johnson was responsible for launching the country’s first all-Black swing band. Their rise to fame was meteoritic and by the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 they had become famous across Britain for their BBC Radio broadcasts. The band also enjoyed a residency at the famous Café de Paris in London’s West End.

At 6’ 4”, the elegant Snakehips had the gift of imparting his terrific enthusiasm for swing music, and his main achievement was to show that Britain could produce a Black bandleader as sensational and classy as Black Americans like Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington.

Everyone who met Snakehips commented how kind and gentle he was. Offstage, Snakehips was the lover of Gerald Hamilton, a memoirist and critic who had served prison sentences for bankruptcy, theft, gross indecency and being a threat to national security. Hamilton was immortalised in Christopher Isherwood’s novel Mr Norris Changes Trains. Snakehips and Hamilton met in 1940 and made a home for themselves in Belgravia, one of the most exclusive parts of London.

In the first year of the war, Snakehips reached the peak of his popularity. The Café de Paris, situated underground, was thought to be impregnable and it was advertised as “the safest and gayest restaurant in town” during air raids which began in September 1940. However, on 8 March 1941, one of the worst nights of the Blitz, two high-explosive bombs crashed onto the dance floor and exploded. Reports of the numbers of dead and injured have varied, but most reports agree that more than 30 people lost their lives, and 60 others were seriously injured. Snakehips was among the fatalities, but when his body was discovered, there wasn’t a mark on it and his red carnation was still in the buttonhole of his tailcoat.

Hamilton was contacted by the police who informed him of his lover’s untimely death at the age of 26 and asked him to come to the mortuary to identify his partner. Thereafter, Hamilton never travelled anywhere without a framed photograph of the young man he described as his “husband”. Hamilton died in 1970.

Patrick Nelson (1916-1963)

Nelson left Jamaica in 1937 and after his arrival in Britain he became an artist’s model. He also became the lover of the Bloomsbury Group painter Duncan Grant. In 1940, Nelson joined the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) but was captured by the Germans outside Dunkirk. He remained a prisoner of war for more than four years.

Berto Pasuka (1917-1963)

A Jamaican dancer, choreographer and painter who arrived in Britain in 1939 and made a living by dancing in cabaret shows in West End nightclubs and as an artist’s model. Pasuka, admired for his fine physique, found himself in demand as a model for sculptors, photographers and painters. These included Angus McBean, whose exquisite photographic portraits of Pasuka have now found a home in the collection at the National Portrait Gallery.

To improve his skills as a choreographer, Pasuka enrolled at the Russian Dancing Academy in King’s Road. After preparing for two years, Pasuka launched Les Ballets Negres, Britain’s first Black ballet company, at the Twentieth Century Theatre in Westbourne Grove in 1946. Critically acclaimed and attracting large audiences, for several years, Les Ballets Nègres toured throughout Britain and visited Holland, Belgium, Sweden, Switzerland, among others. They made their final appearance in 1952.

After relocating to Paris, Pasuka earned a living with a cabaret act and by modelling for a number of painters on the Left Bank. He also became a painter himself.

Gordon Heath (1918-1991)

An American actor, Heath came to London’s West End in 1947 to play a leading role in highly acclaimed Broadway play, Deep Are the Roots. He played Brett Charles, a GI who had served with distinction in wartime Europe, but on his return home to the Deep South is forced to confront racism.

Off-stage, Heath and his partner Lee Payant fell in love with Paris, where they faced less racism and homophobia. They made Paris their home and opened a popular Left Bank café called l’Abbaye, where they entertained customers with their folk-singing.

Heath never completely gave up his acting career. In 1955, he played Shakespeare’s Othello for the BBC and was featured on the cover of the Radio Times. Heath died in Paris in 1991 from an Aids-related illness.

Under Fire – Black Britain in Wartime 1939-45, published by The History Press, is out now

The post Raising the curtain: 15 Black, queer game-changers who made a mark on British culture appeared first on Attitude.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News