Rick Hall obituary

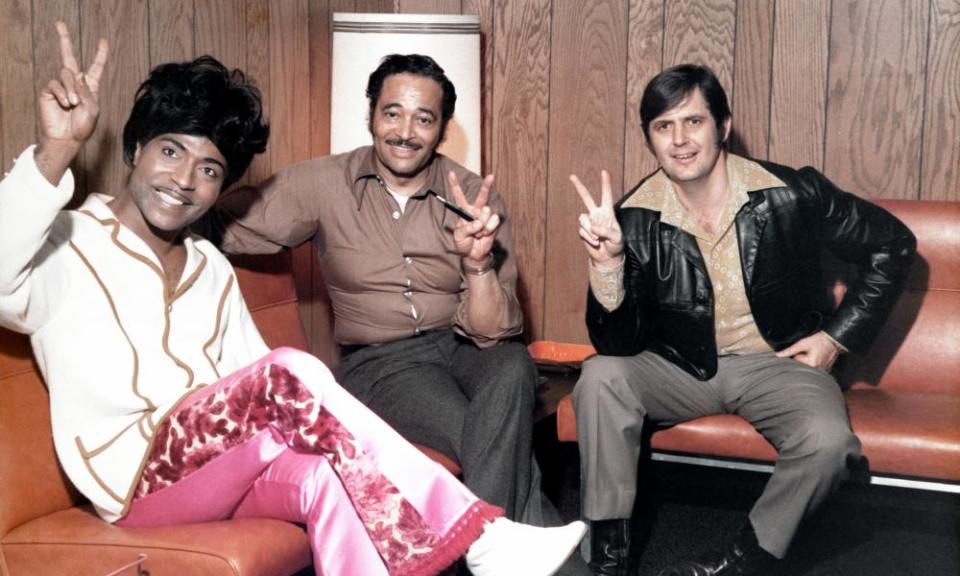

In the music industry of the 1960s, Rick Hall was the epitome of the “record man”, capable of functioning as guitarist, songwriter, music publisher, recording studio proprietor, record label boss and, most significantly, record producer. What made Hall, who has died aged 85, stand out was his position at the confluence of the three key strands of black and white American popular music – gospel, country and R&B – which merged to provide the foundation of so much of significance in that and succeeding decades.

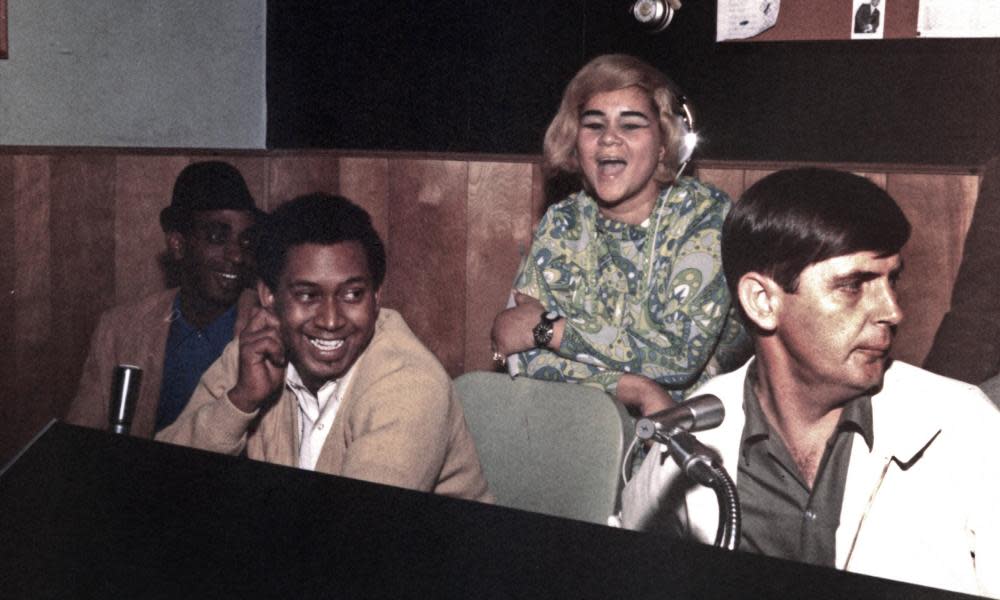

As a hands-on producer at his Fame studio in the small Alabama town of Muscle Shoals, Hall supervised classic recordings by Etta James, Wilson Pickett, Candi Staton and others. Using a hand-picked cadre of musicians, he established a soul-drenched sound and a relaxed ambience that attracted singers and producers from far and wide.

The most significant of those visits was in January 1967 by Aretha Franklin and her producer, Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records. Under an earlier contract with the Columbia label, Franklin had made records that failed to exploit the gospel-trained emotional directness of her remarkable voice. Wexler believed that taking her to Muscle Shoals, one of a group of four small towns straddling the Tennessee river, would put her back in touch with her roots.

On the first day of a scheduled fortnight, as they recorded a song called I Never Loved a Man (the Way I Love You), the atmosphere of Hall’s studio was clearly giving Franklin the freedom to express herself without constraint. Towards the end of the session, however, the singer’s then-husband, Ted White, got into a drunken argument with a trumpeter, and when Hall visited Franklin’s hotel later to smooth things over, he and White came to blows.

Franklin flew back to New York the next day and never visited Muscle Shoals again. But the profound soulfulness of what they had recorded in Alabama caused a sensation when I Never Loved a Man was released a few weeks later, giving Aretha a No 1 hit that set the course of a triumphant career.

Hall was born in Forest Grove, Mississippi, and brought up in Franklin County, Alabama. His mother, Dolly, left the home before his fifth birthday and worked in a bordello. His father, Herman, who worked in a sawmill and later as a sharecropper, was keen on gospel music, and Rick’s first practical involvement in music came at the age of six, when an uncle gave him a mandolin. Eventually he graduated to guitar and began to play in local country bands while working as a toolmaker.

He married for the first time in 1955. Eighteen months later his wife, Faye, died in a car crash, and two weeks later his father was killed when a tractor Rick had bought him overturned. For the next four years Hall disappeared into a haze of drink. He emerged in 1960 when he and two partners started a company based in Florence, Alabama. He had met one of them, Billy Sherrill, the future producer of Tammy Wynette’s records, when they played together in a band called the Fairlanes. They named their company Fame (Florence Alabama Music Enterprises) and opened their first primitive studio above a drugstore.

The big break came in 1961, after the partnership had been dissolved, with Hall keeping the Fame name. A local singer named Arthur Alexander came in with a song he had written, a mid-tempo country-inflected R&B ballad called You Better Move On. Hall liked it, put a small group of musicians together for a recording session, and took the tape to Nashville, 120 miles away, where he licensed it to Dot Records, Pat Boone’s label. The song was the first of Alexander’s run of hits and entered the repertoire of many British groups, notably the Rolling Stones, who recorded it in 1964.

When Hall received a cheque for $10,000 as the initial proceeds of Alexander’s success, he build a full-scale studio in nearby Muscle Shoals: a low cinderblock building in which musical lightning would strike over and over again. Jimmy Hughes’s Steal Away; Maurice and Mac’s You Left the Water Running; Staton’s I’m Just a Prisoner; Clarence Carter’s Patches and Etta James’s Tell Mama were among the Hall productions that attracted the world’s attention to the Muscle Shoals sound.

In 1969, at the height of his success, the core of his finest rhythm section – the keyboards player Barry Beckett, the guitarist Jimmy Johnson, the bass guitarist David Hood and the drummer Roger Hawkins – decamped to set up their own studio. Using the Muscle Shoals name, they attracted custom from the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan and others.

Hall was livid, and the rift had barely healed by the time a prizewinning documentary titled Muscle Shoals (directed by Greg Camalier) appeared in 2013, telling the story of the town’s rise to prominence, with a emphasis on Hall’s contribution.

He continued to produce records – including the Osmonds’ first hit, One Bad Apple, Carter’s Patches, Bobbie Gentry’s Fancy, Mac Davis’s One Hell of a Woman and Jerry Reed’s She Got the Goldmine (I Got the Shaft) – and to supervise his in-house songwriters. The sale of two of his six publishing companies made him wealthy and enabled him to donate a mansion he had built to a charity for abused children from a background of poverty, like his own.

Hall is survived by his second wife, Linda, whom he married in 1968, by three sons, Rick Jr, Mark and Rodney, and five grandchildren.

• Rick (Roe Erister) Hall, record producer, born 31 January 1932; died 2 January 2018

Yahoo News

Yahoo News