Is Russia’s imperial dream really over?

The idea that Russia was, for centuries, an empire is by no means new. Nor is the belief that it remains one even now. Knowledgeable historians calculated that it was once the greatest empire in human history, if one takes into account both the territory it controlled and the timespan its domination lasted.

Adventurous political analysts have argued that in recent times Russia is inclined to regain its imperial powers. As Zbigniew Brzesinski, the former national security adviser to President Jimmy Carter, put it in 1997: “without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire … however, if Moscow regains control over Ukraine, Russia automatically again regains the wherewithal to become a powerful imperial state, spanning Europe and Asia.” The annexation of Crimea is apparent evidence of this process.

Yet many observers believe the present “empire” (ie the Russian Federation) might itself collapse once more, dissolving into different parts. Some politicians hope that it will.

Very few, however, attempt to understand the nature of the Russian imperial project – and the similarities and differences between the Russian empire and the other European ones.

The most striking similarity between the Russian and the western imperial histories – the one that is arguably critical to any European adventure of the kind – is the fact that they were clearly divided into two discrete, consecutive phases.

The first was the period of settler colonisation, by which the applicable imperial power subjugates great landmasses either on its own continent or overseas, and relocates there significant numbers of people, to the point they are able to outnumber the indigenous tribes. This was the case for the Russians in Siberia, for the French in Louisiana and Canada, for the British in the Thirteen Colonies, Australia and New Zealand, as well as, in some senses, for the Spanish in Latin America.

All these appropriations were made between the early 16th and mid-18th centuries and resulted in what Angus Maddison called “the western offshoots”.

The second phase involved more straightforward military conquest; this tended to see locals being dominated by relatively small regular armies and a complicated system of vassalage (like in the case of the British Raj in India). Here Russia followed the western path as well: just as the French conquered Indochina and west Africa and the British took huge parts of Asia, from modern Pakistan to Malaya, and of Africa, from Kenya to Rhodesia, so the Russians added to their empire both the Caucasus and parts of central Asia, confronting the British during the Pandjeh incident of 1885.

In both phases, Russia was as European in its behaviour as either Great Britain or France: it built its empire directed by European logic and using European means of communication and warfare. Nevertheless, between the western method and the Russian approach there was one huge difference.

This divergence surfaced between 1776 and the 1820s as the western European overseas colonies revolted and, led by people who were themselves being entirely “European” in their world view and behaviour, turned themselves into independent entities from Massachusetts to Argentina. This forced the colonial powers to turn to military force effectively to create new, second empires – usually in different places.

In Russia’s empire, meanwhile, neither its Siberian provinces nor the newly “reconciled” lands of today’s Ukraine and Belarus tried to secede. Therefore, while Britain and France in fact possessed two different empires each, consecutively, the first and the second Russian empires (the first achieved through settler colonisation, the second through military action) were simply added to one another, rather like the traditional Russian matryoshka doll.

This key difference between the imperial histories of Russia and the west helps to explain how the European powers have ended up where they are today.

In particular, let’s consider the dissolution of the Soviet Union. With some minor exceptions, the borders of Russia now resemble those that existed in the mid-17th century, the time when the first empires of both Russia and the west powers were almost complete. Therefore, I would argue that the fall of the USSR was broadly the same process which evolved on a global scale between the end of the Second World War and the early 1970s and which is widely known as “decolonisation” (I dislike the word because I believe the European overseas appropriations of the time were not colonies, but rather military controlled possessions).

But whereas this process ultimately left countries like Britain and France without empires at all, today’s Russia lost only its second – by retaining its first, it never lost its ambition for future re-expansion.

Here we should return to history.

The Russian and the western empires were similar as it comes to the timings of their creation and to the methods of their construction – but they differ from each other in terms of the actors that stood behind the process.

In western Europe the major nations (kingdoms then of course) had gained a clear national identity before they started their colonial adventures. Portugal, the oldest European nation state, fully sovereign since 1143, was the first to launch its overseas expansion. France emerged in full grandeur after peace with Britain in 1453 and the defeat of Burgundy in 1482; Spain became united in 1469; and Britain itself evolved as a single state after England was joined by Scotland and Ireland under James I in 1603.

We can see this period as pre-imperial. By the time the Portuguese, the Spanish, the French, and the British sought to expand overseas, their own national unity was beyond question. This meant that when their first empires dissolved towards the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, little damage was done to the sense of national identity of the imperial bases. As a consequence, the later, “second” empires appeared in the same sense British and French, as were the earlier ones.

Contemporary Russia remains and will remain an empire since it simply has no place to retreat to

In Russia, things followed a different path. Moscow, a small settlement at the time when the Kievan Rus’ (the medieval alliance of Slavic and Finnic groups) reached its apex in the 11th and 12th centuries, became stronger when the separated Russian princedoms fought for their liberation from the Mongols.

Till that time, the vast country we call Russia today was united not so much by national or even quasi-national identity, as by its Orthodox faith as well as by the belief that it had become the beacon of the “true” Christian faith after the fall of Constantinople.

The Muscovites overthrew the Mongol domination in 1480 and less than a century later ruined the Mongol khanates in the Volga region and started their expansion to the east. It took them another 100 years to reach the Pacific shores – but in the west they weren’t able to advance further than the current border between Russia and Belarus.

“Russia” as the country’s name became widespread in the mid-17th century as all the three major centres of Russian statehood – Novgorod, Kiev and Vladimir – started to be governed from Moscow. But the key point about this development is that the Russian state emerged as an empire, was administered as an empire, and possessed many other imperial elements. In other words, Russia itself arose as an empire – built not by Russia, but rather by Muscovy. Therefore the first Russian empire was actually the empire of Moscow, and not the empire of Russia.

The Muscovy-built empire called Russia consolidated itself during the 17th and 18th century, strengthening its domination both in its settler colonies in the east and in the “original” “Russian” lands in the west.

Only as this consolidation process was actually completed did Russia begin to conquer militarily neighbouring lands – from Finland in the North to the Caucasus in the south; from Poland in the west to Bukhara and Kokand in the southeast. As such, the second Russian empire became an empire built by Russia, not Muscovy; and in a self-fulfilling cycle, bolstered the sense of a “Russian” national identity.

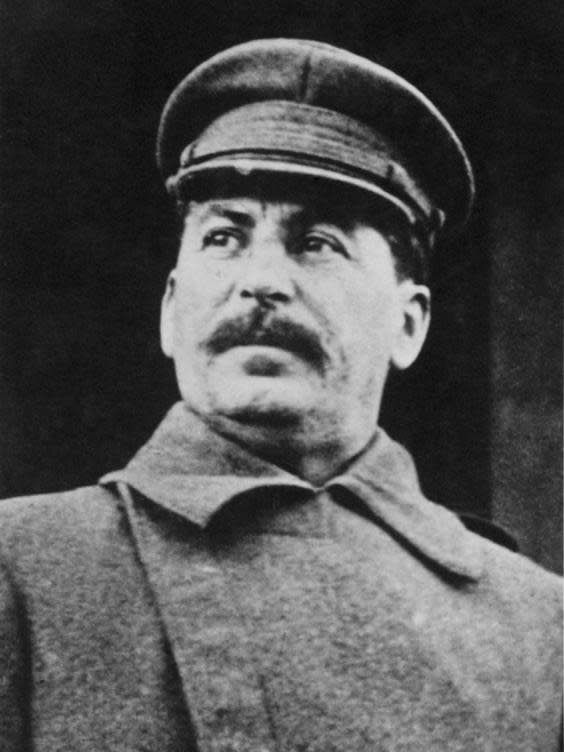

The imperial core of all the western European examples remained the same from beginning to end (Britain, France, Spain etc); in the Russian case, it changed from Muscovy to Russia. Therefore, in the 20th century it was not only Stalin’s will that divided the Soviet Union into different “Socialist Republics”, but rather Russia’s entire history. The vast “country” of the USSR consisted of the Russian republic, which had boundaries similar to the first Russian empire, and all the other republics which replicated the second Russian empire’s military possessions.

It should be noted that while in the USSR-era Russian republic Russians themselves accounted for 81.5 per cent of the population according to the 1989 census. In none of the other Soviet republics did they make even a simple majority.

This history and these demographics were the two major factors that made the Soviet Union ready for speedy disintegration after 1989.

From all this, three crucial conclusions can be drawn.

First, contemporary Russia remains and will remain an empire since it simply has no place to retreat to. As Russia lost its possessions in 1991 it returned to an entity territorially similar to one that started the last wave of expansion in the late 18th century.

On the face of it, it looks like all the other European empires which, during the “decolonisation” of the 20th century were pushed back to those territorial limits from which they began. But while the western imperial cores were and always had been nation states, (some of them democracies and even republics), Russia was itself an empire when it started to expand two and a half centuries ago.

The Russians are European people who share the major European values and principles – but nevertheless Russia as a country arose not as a nation based on these values but as an empire driven by a thirst for power and expansion.

If a nation state builds an empire and fails, it comes back to being a (hopefully better) nation state, one which transcends imperial aspirations. But if an empire constructs an even bigger empire and fails, it reemerges as an offended, revanchist and aggressive empire – exactly as Russia now looks like.

The second I draw is that we should not expect Russia to fall apart, as many current observers suggest. Even though the country remains multiethnic, the Russians make up the majority of the population in almost every part of the country. I cannot think of any cases in which truly consolidated, culturally homogenous country collapses and is divided into parts unless as the result of a war (a prospect for which there are no markers).

Instances of countries existing as divided entities but being inhabited by the same ethnic group or people were all caused by military conflicts (East and West Germany, South and North Korea, North and South Vietnam, continental China and Taiwan).

No foreign force could at present defeat Russia militarily and cut it into parts; moreover, the fear of external powers is so huge in today’s Russia that those parts of the country that used to have some inclination for greater autonomy (like eastern Siberia or the far east), no longer do.

Anxiety in those areas about the growing influence of China outweighs any concerns about growing pressure from and “exploitation” by the (imperial) centre. As Russia becomes weaker in the economic and political sense, any outsider hopes for its dismemberment actually fade.

The final conclusion is the most important and it is this. There is, despite everything, a crucial weakness in the existing political construct of the Russian “Federation”. Inside this federation there are still several regions that look completely alien to it – those that were acquired not during the first wave of empire-building but during the second.

These territories are the entire north Caucasus, which was attached to Russia as a result of bloody wars in the mid-19th century, and the Republic of Tuva at the border with Mongolia that first became part of the Soviet Union in 1944. The north Causasus lands are by no means “Russian”: today the complete share of the ethnic Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian population in the “Russian” republic of Ingushetia is a mere 0.9 per cent. Compare this with remote Kyrgyzstan, a sovereign nation in central Asia, where it accounts for close to 6 per cent.

These parts of the current Russia are elements of the second empire which were incorporated into the first one due to a historical mistake. Things were nearly different: in early 1990s, as Chechnya revolted against the Russian rule, it was thought other regional republics were ready to follow – but it never happened.

Now, Russia claims it “re-established” its control over its former military possessions, although in reality it pays countless tribute to local “khans” and “emirs”. In the end though, these remnants of the second Russia empire will surely secede at some stage.

In sum then, Russia is a unique creature: not so much superior to other European empires, but drastically different from them. These differences shouldn’t be either neglected or denied; one should look on the country sine ira et studio for exploring its European nature and history and for understanding what might be expected from it in the future.

Russia is the last existing empire – and an empire that lasts, if not forever, than for longer than its western equivalents. It should not be criticised for this, but explored and investigated.

Vladislav Inozemtsev’s new book, with Alexander Abalov, is ‘The Last Empire’, published in Russian by Alpina Publishing House. It will be available later this year

Yahoo News

Yahoo News