Serbia’s Strongman Seeks Final Act That Will Decide His Legacy

(Bloomberg) -- Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic joked earlier this year about how he saw the mood of the country he’s led for almost a decade: “People are getting fed up with me.”

Most Read from Bloomberg

Netanyahu, Under Pressure Over Hostage Deaths, Vows to Press On

‘Underwater’ Car Loans Signal US Consumers Slammed by High Rates

The former minister of information for Yugoslav strongman Slobodan Milosevic takes his party into a parliamentary election this weekend telling voters it will be his final act. Vucic’s pitch to Serbs is to let him bow out having sought closure on the last Balkan war and with the country on the cusp of joining the European Union.

Polls suggest the 53-year-old one-time ally of Russia’s Vladimir Putin is headed for a comfortable victory again. Vucic remains Serbia’s most popular politician and his Progressive Party is way out in front. What will be less easy is how he achieves the legacy he wants as the man who remade Serbia.

Serbia’s traditional east-west balancing act was upended by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year, while the country is no closer to normalizing ties with Kosovo, a pre-requisite of EU membership for both nations. Critics also say a hallmark of Vucic’s power has been the stifling of the opposition, media freedom and allegations of cronyism.

Vucic and his party are reminding Serbs they have not been so well off economically since the collapse of Yugoslavia. That’s in part down to business deals he’s done with China, the Middle East and Russia, along with EU countries that collectively have been the biggest source of investment and subsidies.

Serbia’s two biggest exporters are now Chinese, while a Chinese contractor is building a section of the rail link between Belgrade and Budapest, one of the region’s most ambitious projects.

The president, who was re-elected as head of state last year in a landslide, boasts that he’s brought years of stability for the economy and currency and improved the image of a state that was a pariah under international sanctions in the 1990s.

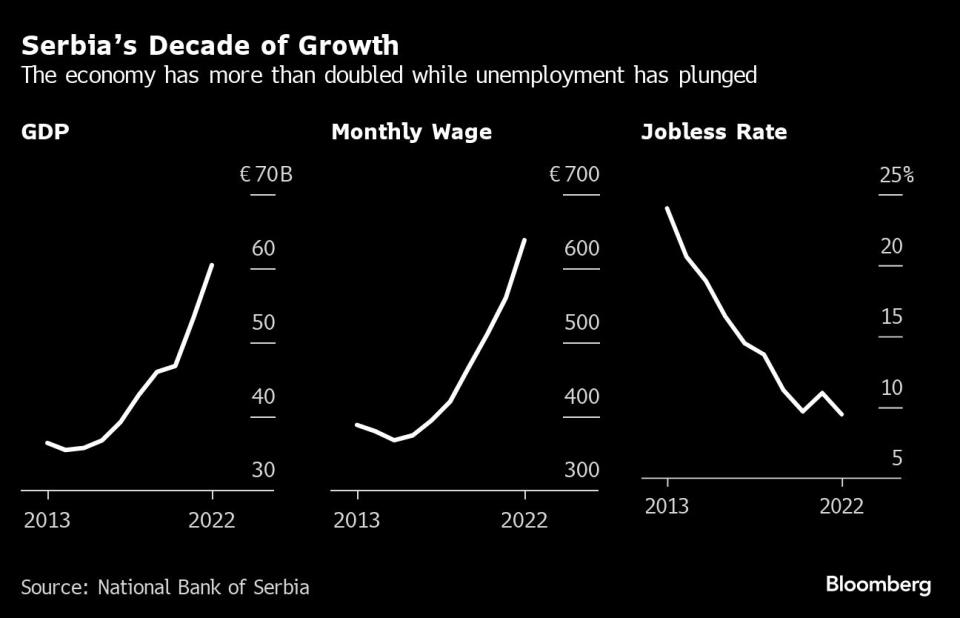

Since Vucic came to power in 2014, first as prime minister, Serbia’s gross domestic product has more than doubled, driven by big ticket infrastructure projects. Serbia attracts two thirds of all foreign direct investment among the six western Balkan states seeking EU membership.

The unemployment rate has more than halved to 9% from 25%. People have felt it in their pockets, too, with Vucic using state handouts to enrich voters. The net average monthly wage has nearly doubled to about $800. Vucic is promising to take that to $1,500 by 2027, the year his current presidential mandate runs out.

Growth in the economy is particularly conspicuous in and around the capital, Belgrade. Cranes dot the city’s skyline.

Milan Stanic, a 56-year-old farmer, used government subsidies to triple the acreage of his apple orchard north of the capital. “I’m the third generation of farmers in my family and we never had this much support from the state,” he said after signing a contract to export fruit to the Middle East and Asia.

Vucic’s opponents, though, say he runs the country more like his own fiefdom than a would-be EU member. They say infrastructure works were funded by excessive borrowing while projects such as the Belgrade Waterfront redevelopment have caused controversy. Vucic counters that debt remains under 60% of GDP, and even his political enemies have bought apartments at the riverside complex.

Tens of thousands of protesters accused Vucic of nurturing the “culture of violence” after two mass murders in May, when lone gunmen killed 19 people in separate rampages. The pro-Western liberal bloc has held weekly protests against the authorities since then, which the president denounced as attempts to exploit the tragic deaths. They’ve since dwindled.

Vucic also is walking a tightrope on the most intractable of issues for Serbia: the future of Kosovo, the state that declared independence in 2008 and yet which Serbia considers its historic heartland.

While Vucic has been criticized by the EU and US for foot-dragging in talks on mending relations with Kosovo, the fact that he remains engaged in them puts him in a precarious position at home. Most political parties don’t want Serbia to ever recognize Kosovo, so — much like with investment in the economy — he needs to seek deals.

One is with former mentor Vojislav Seselj, the leader of the extreme right Radical Party who was indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in the Hague. The Radicals could help Vucic’s team to stay in power at the Belgrade City Hall, which is holding a local election simultaneously with the national vote.

At an interview in his office last month, Seselj summed up the challenge for Vucic. “No one will ever force us to accept the independence of Kosovo,” said Seselj. “Any government that would do that, would instantly fall.” Meanwhile, leaders of two biggest right-wing opposition groups say Vucic is being too soft in EU-brokered talks with Pristina.

Read More: Wannabe Amazon.com Is Ray of Hope in Troubled Corner of Europe Violence in Kosovo Exposes Perilous Limbo in Europe’s Powder Keg War in Ukraine Strains Ties Between Putin and His Old Serb Ally Defaced Putin Mural Tells the Story of Russia’s Waning Influence

Vucic’s party is way ahead, though. It’s polling at about 44% and his Socialist allies, running separately, are slated to win about 10% of votes, easily giving them a strong majority.

The president is also pledging not to change the constitution to enable him to run again after 2027, though he has filled key institutions with allies who would continue to run Serbia. They include Prime Minister Ana Brnabic, the central bank governor and his trusted defense minister, who has taken over the leadership of the Progressive Party.

“There’s a clear mandate for the coming period that must bring us to the point of no return to the past,” Vucic said in a recent interview with broadcaster TV Prva. Once Serbia gets there, the almost 2-meter-tall Vucic said he would be ready to end his term in power — and then train to become a basketball coach.

--With assistance from Slav Okov.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

The Biggest Problem With Lab-Grown Chicken Is Growing the Chicken

Jon Corzine, Steve Aoki and the Art of the Second Act on The Businessweek Show

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News