It shouldn't be up to tech giants to police hate speech, but they must contribute to the cost

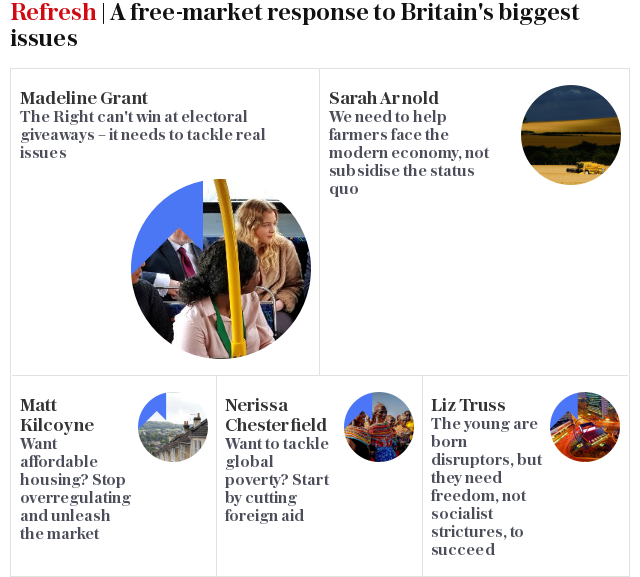

Welcome to Refresh – a series of comment pieces by young people, for young people, to provide a free-market response to Britain's biggest issues

The internet was supposed to be better than this. The promise of limitless, global connectivity was to bring us all closer together, not to polarise and divide us. In the earlier days, social media platforms were talked of as great hubs of political conversation and free expression.

Increasingly, however, the opposite is true, and it is has evolved into a sewer of hate speech and abusive content. So, what, if anything, can be done to turn the tide?

WebRoots Democracy’s research over the past year has been posing the question, to borrow a phrase: "is it possible to have a kinder, gentler politics online?"

Our findings are not surprising. Hate speech and online abuse has infected social media, impacting not just politicians, but normal citizens, too. Users are choosing to self-censor their opinions online out of fear and opting instead to discuss politics in private forums. At the extreme, some told us that the abuse they received online had driven to them to suicidal despair.

Throughout the research, we received stories and ideas from victims, experts, and young people, particularly women and those from minority ethnic groups. While to some, talk of online abuse is merely "political correctness gone mad", to others it is a strain on their mental health and an emotional struggle to express an opinion without the fear of having their existence and identity attacked. It is a big problem which demands big ideas.

We are proposing several ideas to the Government who are currently consulting on their widely-criticised proposals to ban online trolls from standing for elected office. Our ideas are slightly different, with our main recommendation being the introduction of a user-based tax on social media giants called "the Civil Internet Tax". The revenue from the tax would be earmarked for police resources, the creation of a new regulator, and most importantly, spent on digital literacy and anti-discrimination initiatives.

The tax would finally help inject a dose of law and order into online spaces and protect citizens from crimes committed on the internet. How are the police expected to prioritise online abuse on a shrinking budget and with the ever-growing strain of violent crime? Who should oversee the regulation, or self-regulation, of social media platforms? How do we tackle the root causes of online abuse in the long-term? These questions must be answered, and the responses must be funded.

If you are concerned that such a tax is an afront to free markets and would constitute yet more government interventionism, consider the status quo. Social media companies are no longer mere providers of online platforms; they have been lumbered with the responsibility of distinguishing right from wrong, combating extremist content, and identifying criminals.

These responsibilities, which we usually entrust to the entities of the state have been outsourced away from the corridors of Whitehall to the boardrooms of Silicon Valley. Our proposed Civil Internet Tax would help relieve this pressure and allow these companies more space to focus on their founding aims.

Because of the perceived failure of tech giants to pay fair amounts of corporation tax, more and more people are beginning to talk about new ways of taxing them. Philip Hammond, the Chancellor, suggested a vague "digital services tax" may be on the horizon in his party conference speech this year, while the EU are considering plans for a 3 per cent tax on global revenues. Our proposal, however, is different and difficult to avoid. So how would it work?

In order to protect start-ups and smaller companies, the Civil Internet Tax would only apply to revenue-generating, social media platforms which have at least a certain number of users. The tax would be levied based upon the number of UK users and not on profit or revenue.

This system, in contrast to a tax on revenue or profits, would make it difficult for tax avoidance initiatives to be used, while at the same time recognising the value of each individual user. We do not recommend a particular rate, but a levy of £1 would generate an estimated £32m a year from Facebook alone. It would be akin to a tariff levied on the products sold by social media companies, which, of course, is us, the users.

As with other tax models, the number of users that each company has would be self-reported. This number could then be verified against figures displayed in their advertisement offerings. With the industry dependent on platforms being free at the point of use, it is difficult to imagine a circumstance in which this cost would ever be passed onto the everyday user.

If we are to be genuinely serious about tackling the rise of online abuse, we need to consider long-term change which focuses on education and reform. This is what the Civil Internet Tax would provide – funding to ensure the internet can be a safe place free from hate speech, incitements of violence, and behaviour that we would not tolerate anywhere else in society.

Areeq Chowdhury is the chief executive of WebRoots Democracy

For more from Refresh, including lively debate, videos and events, join our Facebook group here and follow us on Twitter at @TeleRefresh

Yahoo News

Yahoo News