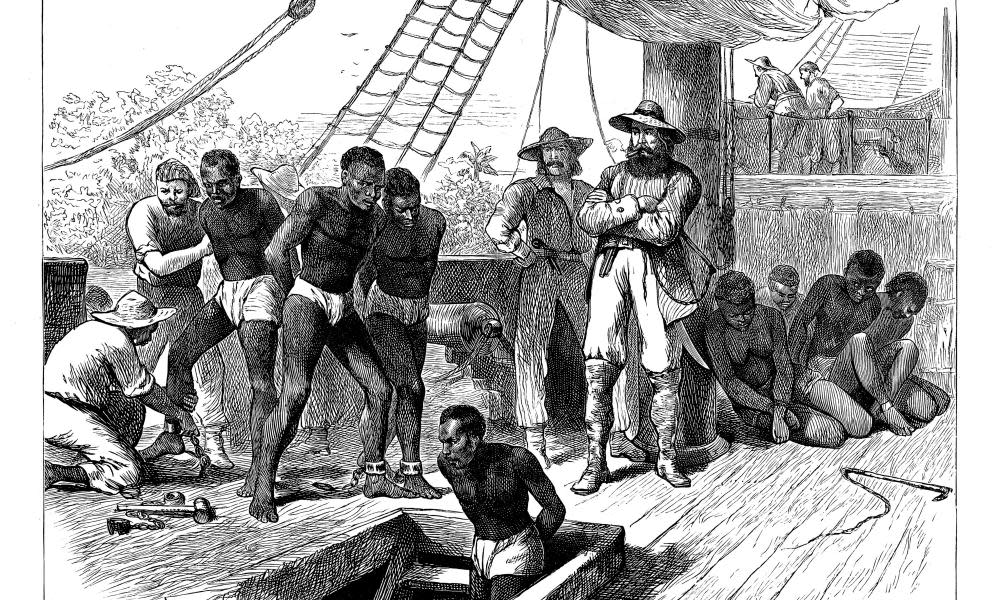

Slaves, serfs, apprentices and property rights

The excellent article by David Olusoga (13 February), together with subsequent letters (15 February), seeks to place the 1833 Abolition of Slavery Act in context. But both sides of the debate follow an essentially Anglocentric approach. The total awards made by the Slave Compensation Commission (£20m) appear “monstrous”, but most contemporaries did not share that opinion. The sanctity of property rights, whether relating to goods, slaves or serfs, underpinned the legal system in Britain and many European countries, while the principle of compensating estate owners for the loss of servile labour was already embedded in European practice.

The Prussian peasant emancipation legislation of 1807, 1811 and 1821 led to an unprecedented transfer of cash and land to aristocratic estate owners (c4.5bn marks). Though serfs were expected to pay compensation themselves, in practice the state advanced a substantial proportion of what was owed to the land-owning class, with the peasants making repayments over an extended time period. Within this context, it is not surprising that the British state was willing to sanction substantial compensation to slave-owners such as John Gladstone, whose son, the later prime minister WE Gladstone, was 23 when the award was made.

Indeed, if we are to fully understand the options available at that time, we need to ensure that future narratives of the 1833 Act incorporate a comparative framework that focuses on the wider processes of emancipating those who suffered from involuntary servitude, whether in the Caribbean or Europe.

Emeritus Professor Robert Lee

Birkenhead, Wirral

• Rosie Turner (Letters, 15 February) argues that “emancipation actually led to the deterioration of black women’s lives”. The reality is more complex. While it is true that the apprenticeship system was often harsh for women, it also offered them more opportunities than slavery. Under the terms of the system, apprentices had the right to buy themselves out of apprenticeship and thereby gain full freedom. Female apprentices did so in significant numbers – in fact, considerately more so than male apprentices.

Apprenticeship also limited the hours that could be worked by both men and women, something unknown during slavery. In addition, under the terms of the apprenticeship, stipendiary magistrates were appointed in part to prevent women from being flogged. Though the legislation was not always observed, apprenticeship nonetheless offered far more possibilities for women than slavery.

Emeritus Professor Gad Heuman

Department of History,

University of Warwick

• Join the debate – email guardian.letters@theguardian.com

• Read more Guardian letters – click here to visit gu.com/letters

Yahoo News

Yahoo News