Space samples suggest ‘new physics’ in cause of violent solar flares

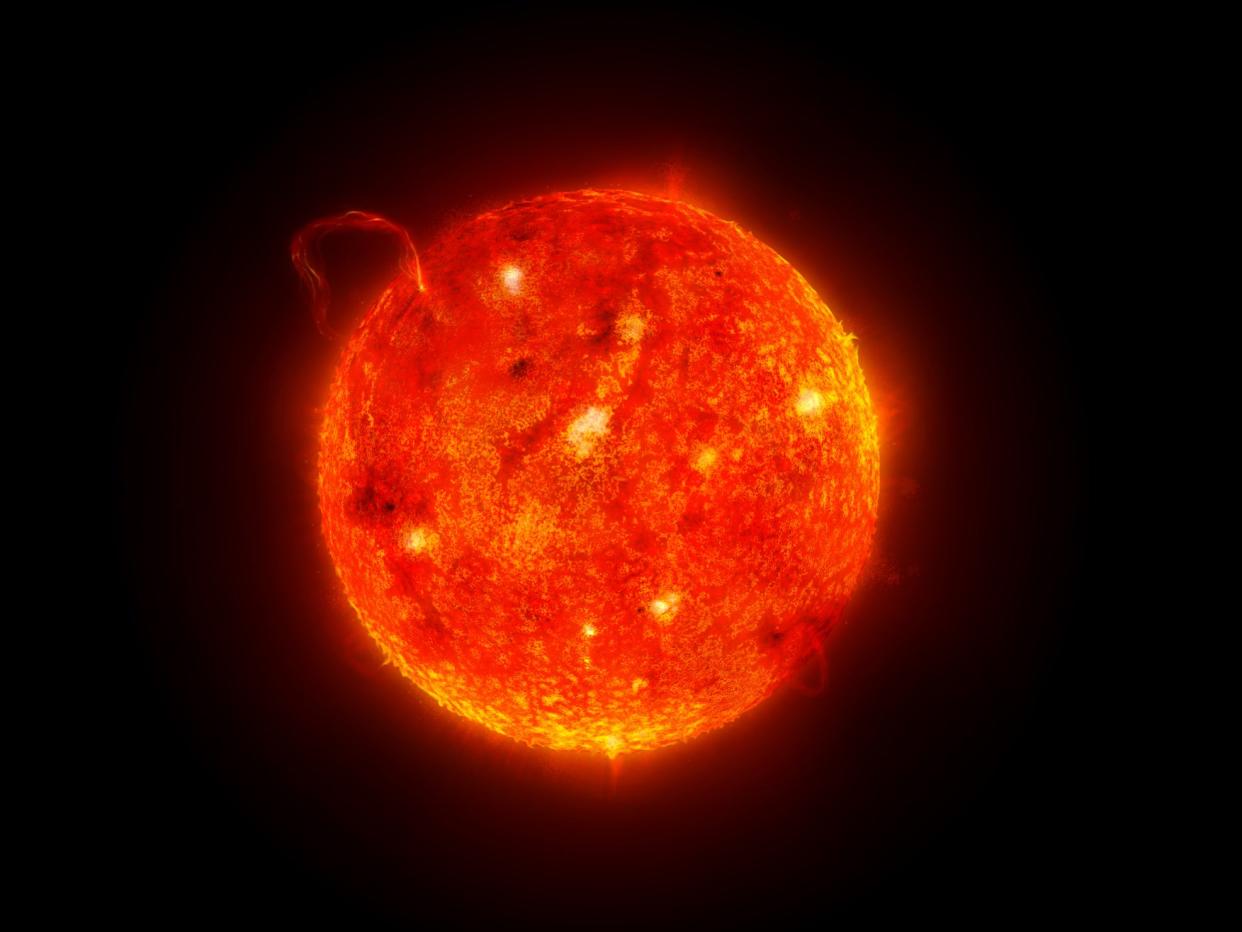

Every day, huge explosions on the Sun erupt with massive amounts of energy, flinging particles out into space.

These events, called coronal mass ejections, largely made up of hydrogen particles, tear through the solar system at speeds of around 2 million miles per hour – this is also known as solar wind.

It is these particles interacting with the magnetic field of the Earth, which is most concentrated at its poles, which cause the shimmering colours of the aurora borealis and aurora australis – the northern and southern lights.

Coronal mass ejections vary in ferocity, and the Sun goes through cycles of heightened and reduced activity.

A powerful flare has the capacity to severely disrupt radio transmissions and cause damage to satellites and electrical transmission line facilities, resulting in potentially massive and long-lasting power outages.

Despite the beauty and the danger coronal mass ejections present, their cause is pretty much a mystery.

But a new study has measured the various levels and ratios of the elements the Sun fires out into space when a coronal mass ejection occurs, and provides new insight into the underlying physics in the Sun that causes these flares.

The study, led by researcher Gary Huss at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa has helped refine understanding of the amount of hydrogen, helium, neon and other elements present in the violent eruptions.

The team investigated a sample of solar wind particles collected by Nasa’s Genesis mission, which returned to Earth in 2004. Genesis was the first spacecraft to return material from beyond the orbit of the Moon.

Most of our understanding of the composition of the sun, which makes up 99.8 per cent of all mass in the Solar System, has come from astronomical observations and measurements of a rare type of meteorite.

But the Genesis samples allowed for a more accurate assessment of the hydrogen abundance in solar flares and other components of the solar wind. About 91 per cent of the Sun’s atoms are hydrogen, so everything that happens in the solar wind plasma is influenced by hydrogen.

The team said measuring hydrogen in the Genesis samples proved to be a challenge. An important part of the recent work was to develop new standards for hydrogen measurement by examining terrestrial minerals with known amounts of hydrogen, implanted with hydrogen by a laboratory particle accelerator.

A precise determination of the amount of hydrogen in the solar wind allowed researchers to discern small differences in the amount of neon and helium relative to hydrogen ejected by these massive solar ejections.

The research is published in the Wiley Online Library.

Read more

Scientists build model of the Sun to study mysterious ‘solar winds’

Weather forecasts from space would help protect Earth from solar winds

Solar, wind and nuclear each supply more electricity than gas and coal

Yahoo News

Yahoo News