Can you spot the green belt land Sunak wants to save? Take our quiz

Click on the pictures throughout this piece that you think are of green belt land

From the road into Sevenoaks town centre, you can spot the promised land. It lies just beyond this Kentish cluster of old pubs and modern bistros, crawling traffic and ambling shoppers: the fiercely guarded countryside, which forms a section of the green belt around London.

Fields, hedgerows and woodland mark out a visible perimeter of dull green in the distance.

Matt Swaby, 46, whose nearby home overlooks a field of sheep, sums up the two sides of an argument that will help mark a divide between the two main political parties at the next election.

“Keep it green,” he says, then reflects: “But I suppose they’ve got to build somewhere.”

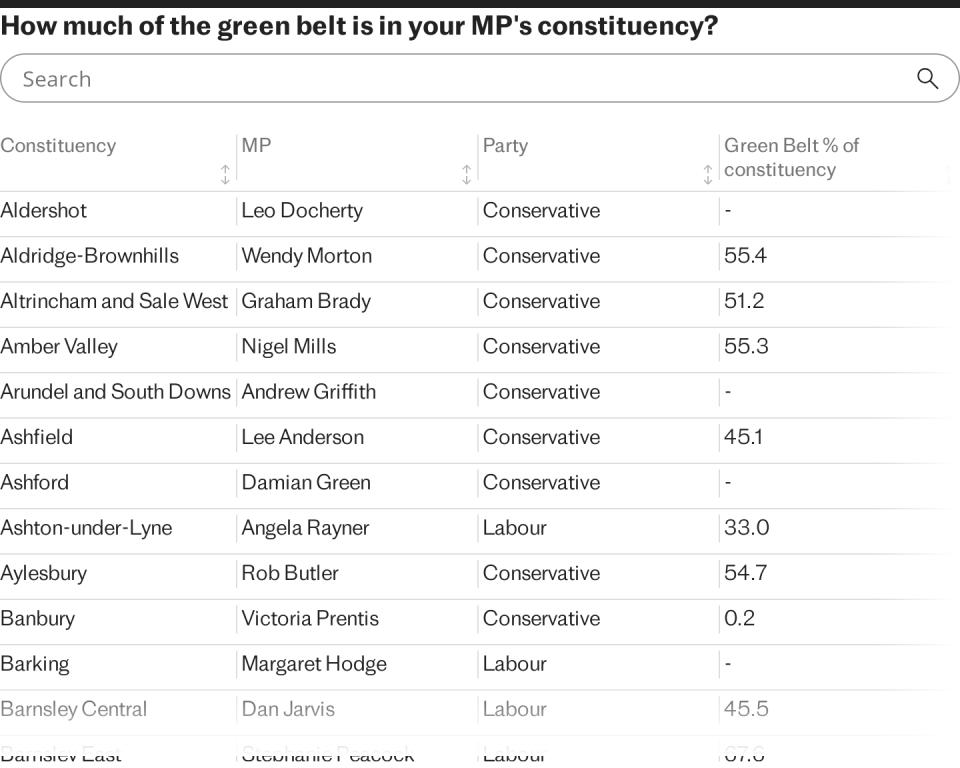

That, indeed, is the problem. Similar landscapes wrap their way around the whole of Britain’s capital, providing what are sometimes called its lungs. They also encircle 14 other urban areas in England, covering 12.6 per cent of the country.

Since the idea of the green belt was enshrined in law through the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947, it has remained more or less sacrosanct, successfully preventing sprawl and the merging of neighbouring settlements. Politicians threaten it at their peril.

Perhaps, that is, until now. In an arguably astute political move, Labour is planning a land grab. While the Tories have shackled themselves to a promise to protect our green belts, Sir Keir Starmer’s party will build on them “where appropriate” to create much-needed housing.

In April, Labour fleshed out its proposal, deploying an unfamiliar phrase to draw the sting from a hotly contested issue. While brownfield land within the green belt (previously developed land no longer in use) would be prioritised for house-building, after this they would look at building on “grey belt” land, they said. They’ve defined this as “poor-quality and ugly areas of the green belt”.

Starmer’s gamble, it seems, is that such a linguistic tweak will help reframe the debate by reminding voters that not all green belt land is created equal. While the term “green belt” evokes bucolic rural landscapes, the reality can be quite different. It can sometimes be a disused petrol station in Tottenham, Labour points out, referring to an oddity of London’s green belt that means a tentacle of it reaches into an area few would mistake for pastoral.

The grey belt category, as envisaged, could incorporate land that has not been built on previously, but lacks natural beauty or environmental merit. Scrubland, for instance, or the “disused car parks [and] dreary wasteland” cited by Starmer previously.

There’s evidence to suggest his gamble might pay off, winning voters around to the idea and pushing Rishi Sunak into an electoral trap. “It is only the Conservatives who will protect the green belt,” the Prime Minister declared last year. “The Labour party will concrete over it.”

These words might once have scared off traditional Tory voters, especially among older generations. But with Labour on the front foot when it comes to backing development, the Tories risk being seen less as guardians of our green and pleasant land, and more as the party crushing the dreams of voters (or voters’ children) desperate to gain a foothold on the housing ladder. Blockers rather than builders, as Starmer would say.

In Sevenoaks, which has among the highest proportion of green belt land in the country, opinions are more mixed than might be expected in the Garden of England. There are, inevitably, some who remain implacably opposed to any development. “I feel quite strongly they shouldn’t build on [it],” says one elderly woman.

“It pains me to see them taking more and more green belt,” agrees Wendy Honeywood, 66, who lives in nearby Tunbridge Wells and worries about plans to build locally “because it’s going to spoil village life”.

How would she feel about grey belt sites being used?

“Perhaps more comfortable,” she concedes.

Richard McLean, 20, who works in a restaurant and lives with his parents, hopes to own his own home one day, but opposes the idea of what he calls “digging up parks”. He says: “It’s good to have all the nice green spaces. Then again, we do need houses somewhere.”

An estimated 340,000 new homes are needed in England each year. Even within green belt areas, there is some appreciation of the scale of the current shortfall.

“People need affordable places to live,” says Angela Woodward, 73, who before retiring worked in planning. “Between the cities there’s a load of [land]. I don’t see what the problem is. People just want their little world to remain the same, and I don’t think we can do that in this day and age.”

Recent polling indicates that Starmer may be pushing at an open door. In November, a survey for the Adam Smith Institute think tank found nearly half of people support building on the Metropolitan green belt if local residents get to share in the profits. A YouGov survey in May last year found that only a third of adults strongly opposed allowing more housing on green belt land. Almost a quarter supported it, rising to almost a third in London. The greatest level of opposition was in the rest of the south of England, where two thirds said they were somewhat or strongly against it.

Separate research by Focaldata last year suggested that more than half of UK adults would support building on the green belt if it was limited to brownfield sites. In key Red Wall areas, such as the Midlands, more than half of those polled on behalf of the communications consultancy Cratus Group said they would vote for a party that prioritised investment in housing, transport and energy infrastructure. Labour was perceived as the party most likely to do this. (Some 41 per cent felt this, while just 26 per cent believed the Tories would be most likely to prioritise it.)

“Roughly speaking, on development the public is basically in favour of things they think will be good for their local area, and particularly for less affluent people in their area,” says James Frayne, the founder of opinion research agency Public First. “But they want to be asked. They hate the idea of stuff being railroaded through without them being consulted.”

He believes the dial has shifted when it comes to the public’s approach to development, not least since many have witnessed up close the effects of the housing shortage. “It’s been brought home to people,” he says. “In large towns and even small cities across England, there’s this sense that our kids can’t afford to live locally, and people are recognising we need more housing stock.”

In rewriting planning rules to strengthen protection of the green belt, has Sunak, then, backed himself into a corner? “It’s not in anyone’s interest to be seen overall as a blocker,” says Frayne.

Some Conservatives are well aware of this. Last year, former levelling up and housing secretary Simon Clarke warned that the Government’s decision to ditch house-building targets was hurting rather than helping the party in south-east England. “We have to make our appeal to all those people, the thousands of young people who leave London frustrated because they cannot own a property of their own,” he said.

But it’s Labour who are acting on this, and will likely reap the rewards – not only in the south-east but in the Red Wall, whose voters are less likely to live in or near protected areas.

“I really don’t see how it helps people in less prosperous regions to allow their house prices to fall relative to those in southern England,” says Paul Cheshire, emeritus professor of economic geography at the London School of Economics. In 2019, he calculated that building on only 1.8 per cent of green belt land across five city regions could increase the housing stock by up to 9 per cent. “You level up by allowing some building in the southern regions,” he says.

You also create a future reserve of grateful Labour voters parked inside traditional Tory areas, suggests Robert Colvile, a director of the Centre for Policy Studies. “For Starmer it’s less about the general election and more to have a licence to build in all those Tory constituencies that have been rejecting [development],” he says.

Earlier this year, property consultancy Knight Frank identified more than 11,000 previously developed sites within green belt areas that could accommodate around 100,000 new family homes. These sites spanned land totalling 13,500 hectares but comprising less than 1 per cent of the green belt. They ranged from builders’ land and old airfields to closed garden centres and vehicle storage facilities. More than 4,600 sat within London’s green belt, which mayor Sadiq Khan has now dropped his pledge to protect.

The London Green Belt Council is worried. It warns that the designation of grey belt sites would incentivise green belt landowners to deliberately degrade the land so it can be considered ripe for development.

“We hear continually of bits of greenbelt land where the owner has killed off the trees and put down pesticides to kill off biodiversity, so it looks – and is measurably – a less valuable piece of countryside,” says Andy Smith, the group’s secretary.

The Conservatives have previously lost control of southern English councils over the issue of giving up green belt land to meet housing targets, he notes.

The danger for Sunak may be present whichever way he turns now.

“It would be challenging for [him] to reverse the policy of green belt protection that he has personally restated many times,” Smith observes.

Back in Sevenoaks, appealing descriptions accompany houses advertised in an estate agent’s window. “Lovely country location,” boast the listings; “fantastic far-reaching views”.

This may be what the green belt suggests to some. But, says Cheshire, “people are beginning to realise the green belt isn’t green”.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News