How Steven Soderbergh Left Hollywood and Got His Mojo Back

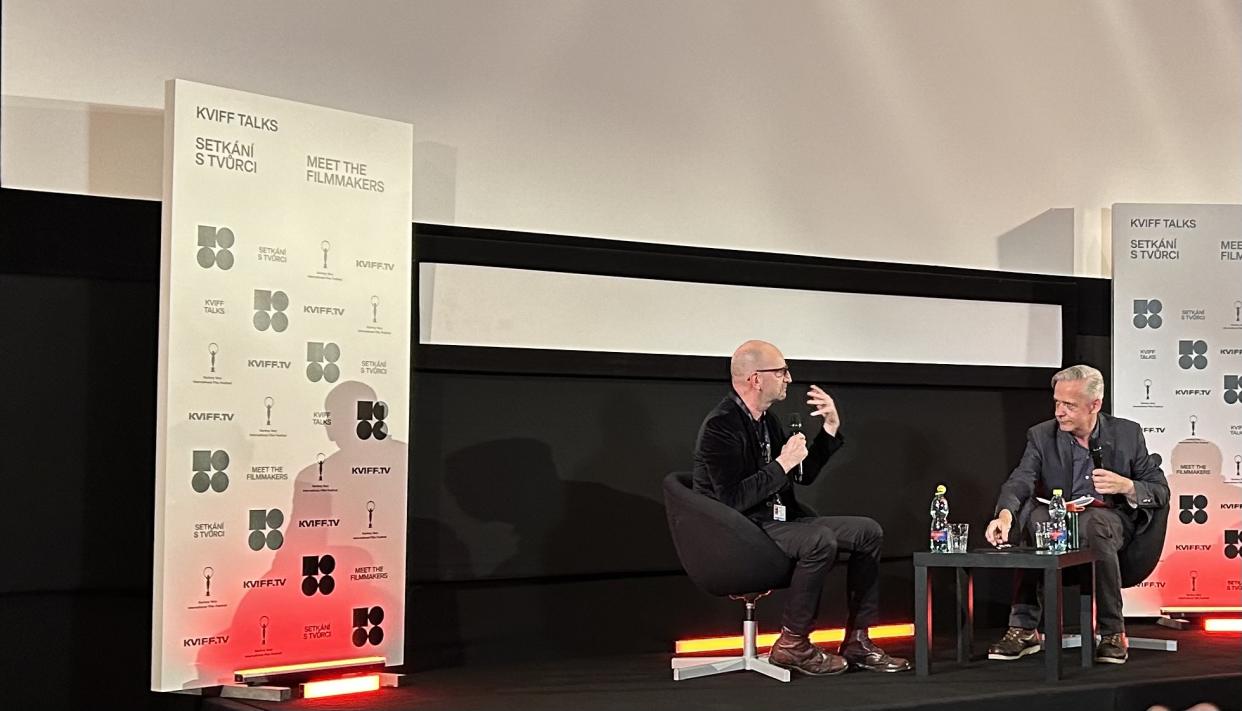

After 15 years of invitations, Steven Soderbergh finally arrived at the Czech Republic’s Karlovy Vary (Carlsbad) for its International Film Festival that celebrated its 58th anniversary this year. The multi-hyphenate, who likes to shoot and edit his films under the pseudonyms Peter Andrews and Mary Ann Bernard (the names of his parents), had two reasons for coming. One, he was closer after moving to London; and two, he wanted to show his sophomore film, 1991’s “Kafka” starring Jeremy Irons and Alec Guinness. He also wanted to present a shorter silent version with a new soundtrack, “Mr. Kneff,” also as part of the festival’s Kafka retrospective. The director gave witty intros to both films and also submitted to a thorough 90-minute grilling by journalist Neil Young.

Many people never saw “Kafka,” which was trounced by critics as the follow-up to “Sex, Lies and Videotape.” Written by Soderbergh collaborator Lem Dobbs, “Kafka” was filmed in what was then Prague, Czechoslovakia, nine months after the revolution, the last film to be made under the auspices of the state-run film industry. Without that control to shoot on empty Prague streets, filmmakers could not recreate that film today.

More from IndieWire

Young pointed out that Soderbergh has worked on more than 35 films in 35 years, not to mention TV. He’s one of six people who have won both the Palme d’Or and the directing Oscar (“Traffic”). He was also nominated that same year for “Erin Brockovich” in that category, and accepted his Oscar having consumed several vodka-cranberries. “I was having a good night,” he said. “I saw all my friends getting up there: Benicio del Toro, Steven Gaghan, Julia [Roberts] won. I was having a fantastic evening and didn’t see this coming at all. I had nothing prepared and said some shit.”

Nonetheless, while he has never watched it, Soderbergh gave a moving speech: “I don’t want to thank anybody,” he said. “I want to thank everybody who spends a little bit of the day creating.” (He denied a rumor that he called the losing directors the next day. “Why would I do that?” he said.)

The two men ranged over a swath of topics. They covered Soderbergh’s high school film training in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where he later shot his Palme d’Or winning and Oscar-nominated “Sex Lies and Videotape,” which also won the 1989 audience award at Sundance and helped launch the indie revolution. They discussed his lifelong obsession with Steven Spielberg’s “Jaws,” which he’s covering in a new book, as well as his mentor, director Richard Lester, who helped him to get through some rough career patches, and Soderbergh’s retirement from directing in 2013.

After “Sex, Lives, and Videotape,” Soderbergh made a couple of films “that didn’t quite work, either creatively or commercially,” he said. “But then I made a film called ‘The Underneath,’ which I knew before we started was not going to work. And that was a really terrifying and depressing experience, too. Two weeks before you start shooting, you don’t want to call the studio and go, ‘I’m not doing that.’ But to sit on that set and be unhappy was something I couldn’t figure out how to solve. I was lost. And I was 31 years old and wondering if I want to keep doing this, which seemed like a terrible situation.”

He decided to try and reclaim his amateur status. He returned to Baton Rouge and shot micro-indie “Schizopolis” starring himself, his ex-wife, and child. He said, “I need to reconnect with what made me passionate in the first place. So I need to go back to Louisiana, put together a crew of the people that I grew up making films with, and make something that was an expression of a legitimate feeling. My marriage was broken up. And I wanted to make something indirectly about that. And it worked. ‘Schizopolis’ was essentially my second first film and kicked off a sequence of films that got me back where I wanted to be. If you’d seen me in 1995, I was not in good shape.”

Lester told Soderbergh that directing would only get harder, but Soderbergh dealt with that by juggling a lot of projects and learning how to keep things sharp. “The job ultimately comes down to a couple of things,” he said. “Your personal taste, what do you like, and then learning and teaching yourself how to achieve what you like. Then the second part of it is filtering. There’s an infinite number of variations of the thing that you’re trying to make. And you’re trying to reduce it moment to moment until you get to the only thing that it wants to be, it needs to be. The only way to get there is by being on the floor for hours and hours and hours. There’s no shortcut. You can’t just leap from one mountaintop to another. And so one of the reasons that I like to keep working is every hour I’m on a film set, I’m learning more about how to refine my filtering process so I can get to what the thing wants to be quicker.”

Making studio star vehicle “Ocean’s Eleven” with George Clooney, Julia Roberts, Brad Pitt, and Matt Damon, among others, was “terrifying,” said Soderbergh. “Movies that are designed to entertain you are as legitimate and necessary as movies that are designed to illuminate you or activate you. And my only demand from a movie that is strictly trying to entertain me is that it be intelligent, and that it not feel like single-use plastic.

“So for me the ‘Oceans’ movies represent an opportunity to play visually in a way that not a lot of movies can justify,” he said. “In my mind, they were these Lichtenstein panels, colorful, big, the music’s very important. There aren’t a lot of movies that you can justify using the zoom lens a lot. And so when that opportunity came up, I jumped at it because I thought it was rare. You just don’t see commercial scripts that were as good as that first script was.”

His enthusiasm didn’t mean it was easy. “I was scared: I’d never made anything like that. I’d never made anything on that scale. It had to deliver pure Hollywood pleasure. And I was nervous and found it not an easy film to make. The cast was lovely and had a great time. I had days of struggling to figure out how to do a specific sequence. We were shooting it totally out of order. And I was really terrified. But I want to be scared, there’s got to be something on every project that I work on that scares me. Otherwise, you’re not alert.”

But then Soderbergh lost it with Hollywood. “I publicly retired 11 years ago,” he said. “I would say, ‘I don’t know what I was thinking.’ But I do know what I was thinking. And what happened was I confused the job with some other issues within the industry or the business that I was unhappy with. And so I announced that ‘Behind the Candelabra’ was going to be my last film for a period. I put out no timeline, I just said, ‘I’m stopping. I’m going to pursue something that I’ve been doing on the side, which is painting, and I’m going to get serious about that, and spend however many years I need to spend to get better at that.'”

“Behind the Candelabra” was the last straw for Soderbergh. Intended as a theatrical movie, the director and his backers had raised $15 million overseas and needed $5 million to make the film. Nobody would give it to them. The numbers wouldn’t work: $30 million to market, $70 million gross to make a profit, no movie like this (Michael Douglas and Matt Damon as Liberace and his gay lover) had ever made that kind of money, etc. So the movie wound up at HBO. Soderbergh thought, “What’s the point?”

Soderbergh was retired for two months when a script for HBO series “The Knick” showed up. He read it, thought, “I’ve got to do this,” and went on to direct all 20 hours.

“I’m a completionist,” he said. “The idea of doing two episodes and handing it over, it’s just not going to happen. In order to do it efficiently, we wanted to board it like a film. So we do all the scenes for all 10 episodes of that year that take place in the surgical room. I fell in love again with the job. I just hate the business. Like, the business drives me crazy. But I need to separate that out. So it got me re-energized.”

The warning signs were there. Soderbergh was appalled when he watched Christopher Nolan’s lauded “Memento” seek distribution for a year: “What is happening? How can nobody pick this up?” Finally, the financier Newmarket Capital created a distribution arm and released it. It grossed $30 million. Soderbergh went on to executive produce “Insomnia” at a time when he and George Clooney were producing partners at Section Eight, trying to help indie projects find commercial release. After six years, Soderbergh bailed because they were too busy for him to pursue his day job.

Always an astute observer of the business, Soderbergh noted that Hollywood just doesn’t work the way it used to. “The heads of the studio, they don’t have the kind of control and power even that they used to have,” he said. “Everything evolves, everything changes. That’s the only constant. So the artist has to figure out how to navigate these changes. The emergence of the streaming platforms is easily the most disruptive thing that’s happened to movies ever. It’s more destructive than television was, it’s more disruptive than home video. This is something nobody quite knows how to wrap their minds around because the economics have changed.”

Soderbergh prefers the old Newtonian economics. Spend two dollars, make four. “Really simple,” he said. “It’s not the world we live in anymore. Now, it’s quantum, ’cause you make a movie on streaming for X amount of money. It’s watched for however many hours, but that’s not a direct return of revenue. That just means people spent this much time watching it. So you have the ability to create the value of that asset. And that’s a new thing.”

But Soderbergh demands more transparency. “They won’t let us look under the hood of how these companies actually work economically. We really don’t know what’s going on at these streaming platforms. And so I theorized, ‘Well, why do people hide things?’ Usually, because they don’t want you to see them, because they’re scared of what you’re going to see. I don’t know where this goes. There’s been a huge course correction. Because the wild west that existed for almost a decade was unsustainable, everybody knew that. But I don’t know what the solve is, because there are elements of it that run counter to economic growth.

“There are two things in the movie and television business that don’t exist on your streaming platform,” he said. “Bonanzas, a film that you put out that makes a billion dollars at the box office, and a TV show that you make that’s a hit, and you do 150 episodes, and you syndicate it for the rest of time. In the streaming world, that cash cow doesn’t exist. So even if you make ‘Stranger Things,’ which by all accounts has been seen by more people than have ever seen anything, at a certain point everybody who wants to see it will have seen it. And it’s just a dead asset sitting there, taking up terabyte space on the platform.

“So I just don’t know how over time this works: You’re spending more and more money to chase fewer and fewer eyeballs. I’ve made movies for the platforms. They were movies that probably would not have gotten made by a traditional studio. But I like the simplicity of: You make a movie and you put it out and it either works or it doesn’t work.”

Soderbergh isn’t giving up on two-hour movies. “I’m still convinced that the feature-length story, the two-hour narrative is not going to go away. I could be wrong, but I’m told, at least in the United States by two of the independent distributors that I’ve been working with, they’re now seeing a wave of young people in their early 20s who are going to the movies and want to see something that is not a piece of ‘IP,’ that is part of a larger franchise. There’s a wave of young people familiarizing themselves with cinema, and going to the movies regularly. And it’s been on the rise over the last few years. That’s encouraging.”

Next up: Soderbergh’s back on a big-scale movie with stars, this time David Koepp’s “Black Bag” with Cate Blanchett, Michael Fassbender, Regé-Jean Page, Marisa Abela, Naomie Harris, Pierce Brosnan and Tom Burke. But the budget isn’t anywhere near $65 million, he said. “It’s a spy movie, but it’s also a love story. It’s about a marriage at its core, and there are no chase sequences or anything like that. It’s an intimate relationship film about people who work in the intelligence service. But super-entertaining, and fun. There’s a 12-page dinner scene that scared me. But one of the things that kept me calm was the six people sitting at that table.”

Soderbergh is finishing things up in the editing room before he hands it over to Focus Features, who will finalize distribution plans.

Best of IndieWire

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News