"I still remember it vividly": two Holocaust survivors on loss, survival and their belief in others

Ordinary people. We see them every day; on our commutes to work, sitting on the benches in our local parks, pushing trolleys around the supermarket.

Ordinary people have the capacity to do fantastic and selfless deeds. They can also actively take part in – or be complicit in – events that are remembered as some of the darkest the world has ever seen. 80 years ago, amid war-torn Europe, the influence of Hitler’s Nazi Germany swept the continent – and the genocide known as the Holocaust began.

Holocaust Memorial Day takes place each year on 27 January. It remembers the six million Jews and other victims murdered in the Holocaust – as well as later genocides, such as those in Bosnia, Cambodia and Rwanda.

Each year, a different theme is explored to help reflect on the Holocaust and provide education; and this year's is “ordinary people.” To mark the commemorative day, I wanted to speak with survivors about their experiences during the Holocaust and document the ways in which they saw people behave – to gain an understanding of how this has impacted their views on the world and humanity to this very day.

During the Holocaust, there were people who were contributors and facilitators during a period of genocide. Yet, there were also people who were resistors; who risked their lives to help rescue those who have lived to give their testimonies today. "It is a strange concept – ordinariness – when we are talking about the Holocaust, because the Holocaust was extraordinary" says Karen Pollock CBE, Chief Executive of the Holocaust Educational Trust (HET). "The people that the Holocaust affected were ordinary. They were men and women who went to work, or stayed home and looked after the children, who went to synagogue – or didn’t. Who enjoyed the same things as we do – cooking, or music, or going to the football. They were children – 1.5 million murdered children – who went to school, who played with their friends, who didn’t always listen to their parents."

I am put in touch with two Holocaust survivors via HET – which works with survivors to give talks in schools, universities and educational settings, enabling survivor stories to be heard by extensive groups of people. "The Holocaust shook the foundations of the modern world, it shaped our laws, our understanding of democracy, our understanding of humanity," says Karen Pollock. "In remembering the horrors of the Holocaust, we know that young people become sensitised to the world around them, and aware of where antisemitism and hatred can lead, they will be voices for the future, speaking out wherever it is found."

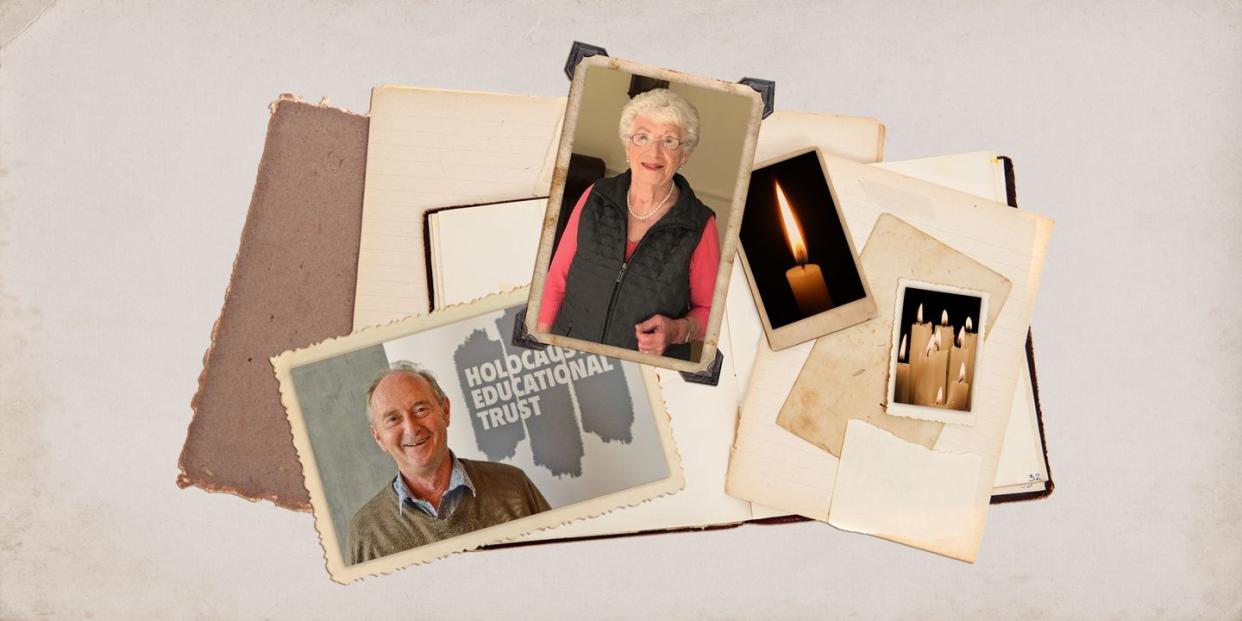

It is through HET that I meet Marcel Ladenheim. From the get-go, Marcel strikes me as a larger-than-life character. He is a joyous and often breaks from our conversation to talk about his family or crack jokes as we talk over Zoom – a medium he uses regularly to speak to school groups about his experiences during the Holocaust.

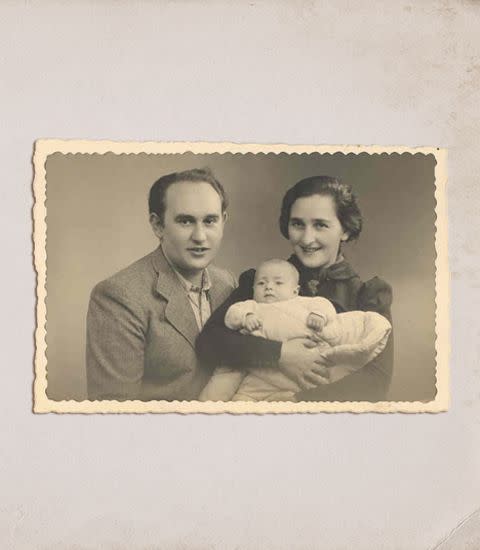

Born in Paris in 1939, Marcel survived the Holocaust by being hidden. Despite being split up from his parents and brother, he speaks of the two women who hid him, the Masoli sisters, with a huge level of fondness. Talking about his invariably happy memories with them, he shares a mischievous grin while recounting that the younger sister, Olga Masoli, had an “extraordinary” profession as a dancer working at the Folies Bergère cabaret club, made infamous by the likes of Josephine Baker and Édith Piaf. While Marcel has more positive memories of his time during the war than might be expected, he also introspectively reflects on his fate compared to others. “Did I see anything horrible? The answer is no. Fortunately, I didn't end up in a concentration camp, or have to witness my family being shot, which is what happened to a lot of the people who didn't survive." Continuing with his reflections, he says he “survived in a happy environment” but knows others weren’t as lucky. “I didn't have that experience, but I am aware of what happened in the concentration camps. There were ordinary people who did terrible, terrible things; who lead ordinary lives and all of a sudden acquired an incredible amount of power. People like Adolf Eichmann, who went on to use terror to do horrific things.”

While Marcel may have avoided the concentration camps, his contemplation on those who didn’t is factual yet emotional, which is only made more haunting by the fact that his father was taken away to a concentration camp at 31 years-old and later died in Auschwitz. Post-war, Marcel lived with the Masoli sisters until 1948, but then came to the UK with his brother. By this time, his father had been murdered and his mother was admitted to a hospital for the rest of her life, having been traumatised by what had happened to their family. So, I ask him, how can life ever be ordinary again – and how can he come to terms with what other human beings can do to one another? “In 1943, I was told to knock on the door of two sisters, two ordinary ladies. They took in a little Jewish boy until the end of the war, despite the risk,” he tells me. “My general feeling regarding people is a very positive one.”

In addition to putting me in touch with Marcel, HET also introduces me to Gabriele Keenaghan. Again, we meet on Zoom, me from my kitchen in South London and she from her living room in North-East England. Like Marcel, what immediately strikes me about Gabriele is the positivity she emits, even over video call. I ask her how she is, and she responds with “as well as I can be at 96” with a grin on her face.

As Gabriele is 13 years older than Marcel, she remembers more about life in the build-up to the Holocaust, before she came to the UK via Kindertransport — a rescue effort to move predominantly Jewish children from Nazi-occupied areas. She tells me of her time in the Jewish area of Vienna before the war (“Leopoldstadt, like the play”) and her memories of being raised by her “extraordinary” grandmother, "who generously gave her time to look after me” following the death of Gabriele's mother. Gabriele’s father was a businessman who worked away regularly, so she spent time with her grandmother and later attended a convent boarding school, which was made possible as while her father was Jewish, her mother had been a Catholic.

Gabriele has happy memories of the convent school and the “very kind” nuns who looked after her. However, this all changed with Anschluss – the Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938. Prior to this, Gabriele told me her father being Jewish “didn't mean anything to me” – but this all took a startling turn when the Nazis gained power. While Gabriele was still allowed to board at the convent, the Nazis stopped the nuns from providing education, so the local authority had to find a new school for her to attend. While her friends were all sent to a different school together, Gabriele was sent to a Jewish school – and forced to wear a yellow star. As she recounts her journey to school with the yellow star sewn onto her coat, Gabriele’s face turns dark. “This is when I realised I was different,” she says. “I met hostility as people would call me names and throw things at me – it was a very painful experience.”

With the Nazi regime continuing to gain power, next came Kristallnacht — the state-sponsored event that saw hundreds of synagogues burnt down, Jewish owned shops looted and large numbers of Jews physically attacked and arrested. “I still remember it vividly,” Gabriele recounts. “The nuns closed the shutters on the windows to try and keep out the noise, but they couldn't stop it. You could hear the crashing of glass and the shots being fired."

It's hard to listen to this account without feeling horrified, especially considering that Gabriele was just 11 years-old at the time. However, following this, her family's situation only got worse. "The day after Kristallnacht was my 12th birthday and we had made plans to celebrate," she tells me with a deep expression of sorrow. "But my father never appeared. He disappeared on Kristallnacht – and I never saw him again.”

Now incredibly anxious about Gabriele's safety, her grandmother arranged for her to travel to the UK on Kindertransport. Despite a terrifying train journey that departed the station at midnight and was regularly interrupted by Nazi guards terrorising Gabriele and the children she travelled with, she made it safely to the UK.

Like Marcel, I am in awe of how Gabriele can seem so positive and have such an enthusiasm for life after the way she saw people behave. She speaks with immense warmth about her family, be that memories of her grandmother (who managed to survive the war and had regular contact with Gabriele for the rest of her life) or memories she’s making with her three grandchildren, and ends our call by wishing me a “good, happy and healthy life – as this is all we can ask for.” Despite her experiences in Europe, she focuses on the people along her journey who showed her kindness – from the nuns in the convent school and the Catholic Committee for Refugees to the first family she worked for in the UK after training as a nanny. “I've met all these people in my life, just ordinary people, yet they are extraordinary in their actions. I think that so many people have extraordinary gifts and the ability to share them.”

In many ways, Marcel and Gabriele's experiences and views of the world and people are heartwarming – yet we cannot forget that they experienced one of the most horrific events in recent history. "The Holocaust took place in living memory, in countries just an hour’s flight from us in the UK," Karen Pollock reminds me. "It was unprecedented in human history, an unparalleled historical event. The experiences of Jews across Europe during the Holocaust were far from ordinary – living in fear, in hunger, in degradation; hiding, living in ghettos, being forced to undergo ‘Selektions’ where Nazi doctors determined who was fit to be worked to death and who would be sent to the gas chambers."

What I am struck by, speaking to these survivors, is that they tread the most remarkable line between ordinary and extraordinary themselves – encompassing both sets of qualities. Marcel spent his life working as a dentist while Gabriele worked her way up in education to become a headteacher — and they both went on after the war to get married and have families. Yet, the very fact they were able to do this is extraordinary. Six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust, but Marcel and Gabriele are here chatting away on Zoom. Today they talk with me, but next week they will be sharing their stories with schools and universities across the country. They both offer contemplative and honest commentary on their experiences – discussing both their and sorrow and happiness – in a way that can only be described as extraordinary.

I ask them both for insight into their life-affirming philosophies and how they feel about the people they have come across in their lives – as the duality they have witnessed seems almost too surreal to imagine. “I think ordinary people are generally kind and considerate, particularly now that I'm getting older,” Marcel says. “I'm always impressed by people – even with small acts like standing up for me on the bus and letting me have a seat. Overall, I think ordinary people are excellent.” As for Gabriele, she gives an astute half-smile. “During my life, I have been shown more kindness than I have hostility, and this has led me to believe that people in general are not unkind. I have met so many wonderful people and my life has been blessed in many ways.”

For more information on Holocaust Memorial Day 2023, you can visit the Holocaust Memorial Day here.

Gabriele Keenaghan BEM and Marcel Ladenheim BEM share their testimonies in schools and colleges across the UK through the Holocaust Educational Trust’s Outreach Programme, which gives tens of thousands of young people every year the unique opportunity to hear the first hand testimony of Holocaust survivors. The Holocaust Educational Trust works in schools, colleges, workplaces and communities across the UK, ensuring that everyone everywhere has the opportunity to learn about the Holocaust. Find out more about the work of the Trust here.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo News

Yahoo News