‘Swamp Dogg Gets His Pool Painted’ Review: A Cult Musician Gets a Fittingly Warm and Quirky Documentary

Isaac Gale and Ryan Olson’s Swamp Dogg Gets His Pool Painted isn’t the sort of “important” documentary that generally wins awards, but it’s a fine example of something even rarer: a documentary that draws its voice and aesthetic from the spirit of its subject, resulting in a tight 97 minutes that feel organic and satisfying and, as befits that subject, appealingly odd.

When it comes to Swamp Dogg, I’m not sure if there’s a middle ground between “Who?!?” and “Swamp Dogg is the BEST!!!” though perhaps Swamp Dogg Gets His Pool Painted will create an appreciative warmth in that space.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

'Office Space' Reunion: 10 Things You Didn't Know About Mike Judge's Classic

SXSW: Dev Patel Gets Standing Ovation for Directorial Debut 'Monkey Man'

Swamp Dogg has acquired his position as a musical cult icon by virtue of an astonishing adjacency to fame that dates back to his first recorded song in 1954. In the subsequent 70 years, he’s been signed to, recorded for, and even been an executive at possibly dozens of labels. He’s written or performed in every imaginable genre and practiced his art up in every musical hotbed in the country. He’s an under-appreciated hip-hop pioneer as one of the shapers of the World Class Wreckin’ CRU. He started his own label (and sold tens of thousands of copies of Beatles covers recorded by dogs). He was a featured participant in Jane Fonda’s anti-war Free the Army Tour. He’s 81 and it was just announced this week that he has a new album on the way.

Swamp Dogg has lived a LIFE.

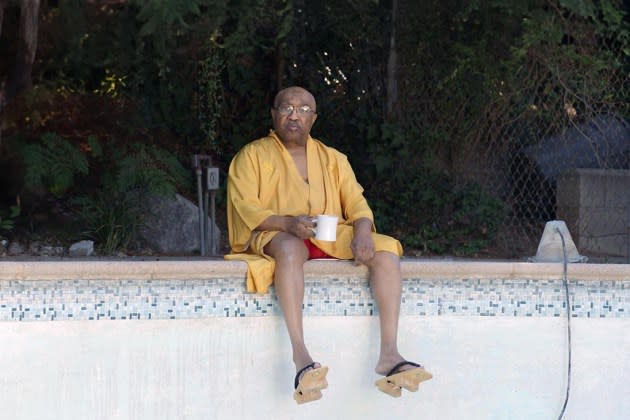

Though at some point Swamp Dogg was straight-up wealthy — he reflects on his fleet of unnecessary cars — he currently resides “Somewhere in The Valley” in a reasonably comfortable, but far from opulent, ranch-style house. From his garage to room after room, the house is packed with the detritus of fame adjacency. Golden and platinum records. Boxes of memorabilia. A vintage Wurlitzer.

His house is also packed with roommates who, like Swamp Dogg, are lifelong musical professionals who have flirted, directly or indirectly, with celebrity. Guitar Shorty spent his own seven decades on the road gigging with some of the biggest names in rock and blues and R&B, influencing better-known legends and even winning on The Gong Show. Jack-of-all-trades Moogstar is even further from being a household name, but he definitely got called up to the stage during the taping of Mark Curry’s comedy special The Other Side.

Swamp Dogg didn’t charge either man rent. It was just three men who, when they weren’t on the road together or separately, would use the home’s various recording facilities or just sit around the swimming pool shooting the shit.

“I like to call it the Bachelor Pad for Musicians. Aging Musicians,” says Jeri’s daughter, whose last name is not “Dogg.”

Did I mention that the pool is being repainted?

It’s a version of fame that’s unique to the outskirts of Los Angeles, and it’s all real, though as the Mark Twain quote that starts the documentary puts it, “The only difference between reality and fiction, is that fiction needs to be credible.”

By the time Swamp Dogg compares himself to Twain in the documentary’s closing moments, it’s a surprisingly credible claim. He’s a natural raconteur, a chronicler of a weird corner of the American experience and a purveyor of homespun wisdom like this utilitarian philosophy of life: “Overall, just be cool. You know? And it’s all so fun, being yourself. That’s fun like a motherfucker. But you’ve gotta find yourself.”

Swamp Dogg’s house is cluttered and his life has been cluttered and Gale and Olson let clutter stand as a guiding principle for the documentary. Sometimes Swamp Dogg’s memories are conveyed through slightly animated photos and television appearances — the man seems to have been made for public access TV — but the doc just as frequently detours into parodied infomercials or, in the case of one elaborate Moogstar tall tale, a solid reproduction of a vintage Scooby-Doo cartoon. The directors love a good drone shot of the Valley neighborhood, each affluent slum with its own pool, each presumably in need of literal or metaphorical painting, each accompanied, presumably, by its own Swamp Dogg-level of star.

Instead of formal talking head segments, Swamp Dogg, Moogstar and Guitar Shorty are mostly just sitting by the pool chattering, but when they sense the documentary needs a different energy, Gale and Olson bring in recognizable Swamp Dogg admirers and alleged neighbors like Tom Kenny and Johnny “Johnny Knoxville” Knoxville. Are Kenny and Knoxville actually Swamp Dogg’s friends or neighbors? Perhaps yes, perhaps no, but the notion that SpongeBob and the guy from Jackass would hover in his sphere is, yes, credible.

It’s all tied together with psychedelic “character” introductions and titles, a font choice anarchy that will offend design purists and that fits the feeling of the documentary perfectly.

Overall, Swamp Dogg Gets His Pool Painted — and the completion of the paint job is one of several milestones, happy and sad, to occur in the film — is good for a few laughs, possibly some tears and a level of reflection that is at least adjacent to profundity.

Whether or not you know Jerry “Swamp Dogg” Williams when the documentary begins, it’s easy to walk away feeling like this is pretty much exactly the spotlight that Swamp Dogg deserves.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Yahoo News

Yahoo News