Treasure and intrigue: scientists unravel story of 1740 Kent shipwreck

Covered with seaweed, bits of shell and pebbles concreted into lumps of corroded iron, the wooden seaman’s chest from the Dutch East India ship Rooswijk remains tantalisingly locked after almost 300 years. It will take months of conservation work before the archaeologists discover whether it holds some of the silver treasure the ship was carrying, or a long dead sailor’s old socks.

A joint excavation by divers and scientists from Historic England and the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands is unravelling the story of the last hours of the Rooswijk, which ran aground and sank in the Goodwin Sands off Kent in January 1740 with the loss of every life on board – almost 250 sailors, soldiers and passengers.

Finds brought ashore in Ramsgate include a shoe still showing the dint of the sailor’s heel on the instep, glass bottles and a fancy wine glass with an air twist stem, which must have come from the captain’s cabin, pewter jugs, an onion jar, tiles from the cooking stove still scorched by the last meal, three wooden chests, one human thigh bone – and some genuine old-fashioned treasure in the form of beautiful Mexican silver dollars, minted just a few years before the wreck, and older, cruder chopped-up pieces of eight.

Several cannon and two huge sea anchors still lie in the silt on the seabed.

A quantity of silver was salvaged in 2005 and returned to the Dutch government, which owns the wreck, but the project leader, Martijn Martens, maritime cultural heritage manager at the Netherlands agency, said it had no idea how much silver was on board.

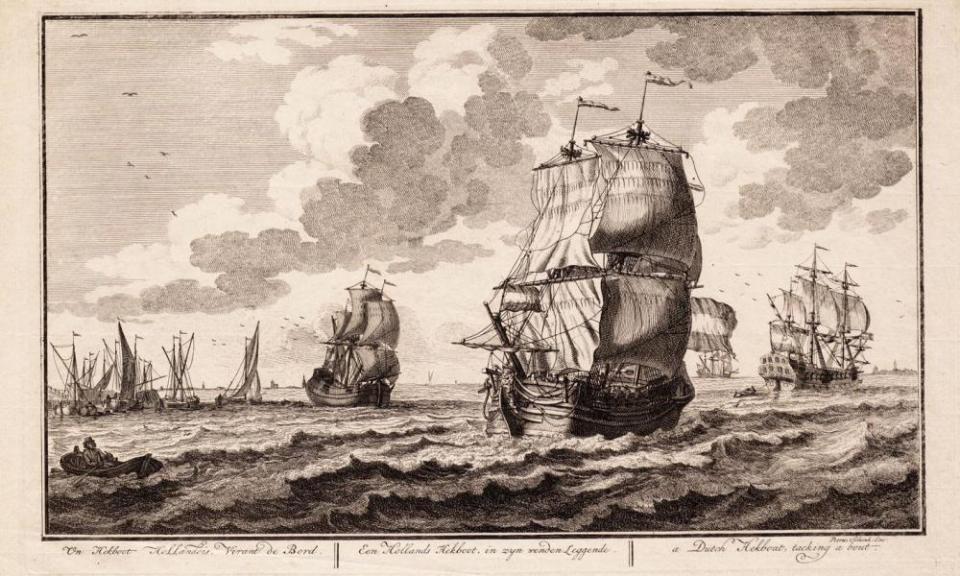

“We have many questions,” Martens said. “We do not even know what this ship really looked like.”

The ship was bound for Jakarta to buy spices and porcelain and was carrying silver bullion and ingots. But silver was worth far more in the East Indies than in Amsterdam, and smuggling – at every level, from a chestful in an officer’s cabin to a few coins stitched into a sailor’s belt – was a well-known way of supplementing wages.

The first finds of silver scattered in small quantities throughout the wreckage are bearing this out, and also show that those who couldn’t afford silver were bringing any kind of scrap metal they could lay hands on, knowing it would all have a value at their destination.

In 1740 it was months before anyone wondered what had happened to the Rooswijk, and it was only when the ship failed to make landfall at the Cape of Good Hope, after what should have been months at sea, that the company began to worry.

A chest of letters washed up on the English coast revealed the truth: the ship, only a few years old and on her second voyage, having left Amsterdam on 7 January, had been driven by a storm the next day on to the Goodwin, the dreaded Ship Swallower, which has claimed the lives of thousands of seafarers – a 19th-century steam ship lies on the seabed 100 metres from the 18th-century three-master.

The evidence from the wreck site is that the heavily laden ship sank like a stone, with the loss of everyone on board.

The ship is an officially protected wreck site because of its historic importance. Of the 250 Dutch East India ships known to have been wrecked, only a third have been located and this is the first to be scientifically excavated.

The excavation was judged urgent because the deep silty sand that has protected the remains for so long is shifting now due to changing tidal patterns, leaving timbers exposed and decaying – and vulnerable to treasure hunters.

It may never be possible, or even desirable, to open the mystery chest. Conventional x-rays often don’t reveal much of heavily concreted objects. Angela Middleton, a conservation expert at Historic England, hopes to persuade the customs authorities to bring along one of the scanners they use at the port to check for people and goods hidden in lorries, and see if it shows up anything.

“We might find out it is impossible to open the chest without destroying it. Or we might find out what is in it and decide it’s just not worth even trying to open it,” she said.

Manders described the Goodwin Sands as “a treasure trove for archaeologists”. There have been protests over plans by the Dover port authority to dredge there to improve the shipping channel and also extract sand and gravel for docks development work.

The sands also became the last resting place of many downed Battle of Britain air crew, and others lost in the second world war. Sir Mark Rylance, who starred in the recent blockbuster film Dunkirk, described the proposal as disrespectful and insensitive.

Alison James, a maritime archaeologist at Historic England, said it was in discussions with Dover, and though the Rooswijk lies some distance from the proposed dredging area, it would be monitoring its condition and the other protected wrecks.

There will be open days on which the public can see many of the finds at the excavation’s warehouse base in Ramsgate Marina on 19 August and 16 September.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News