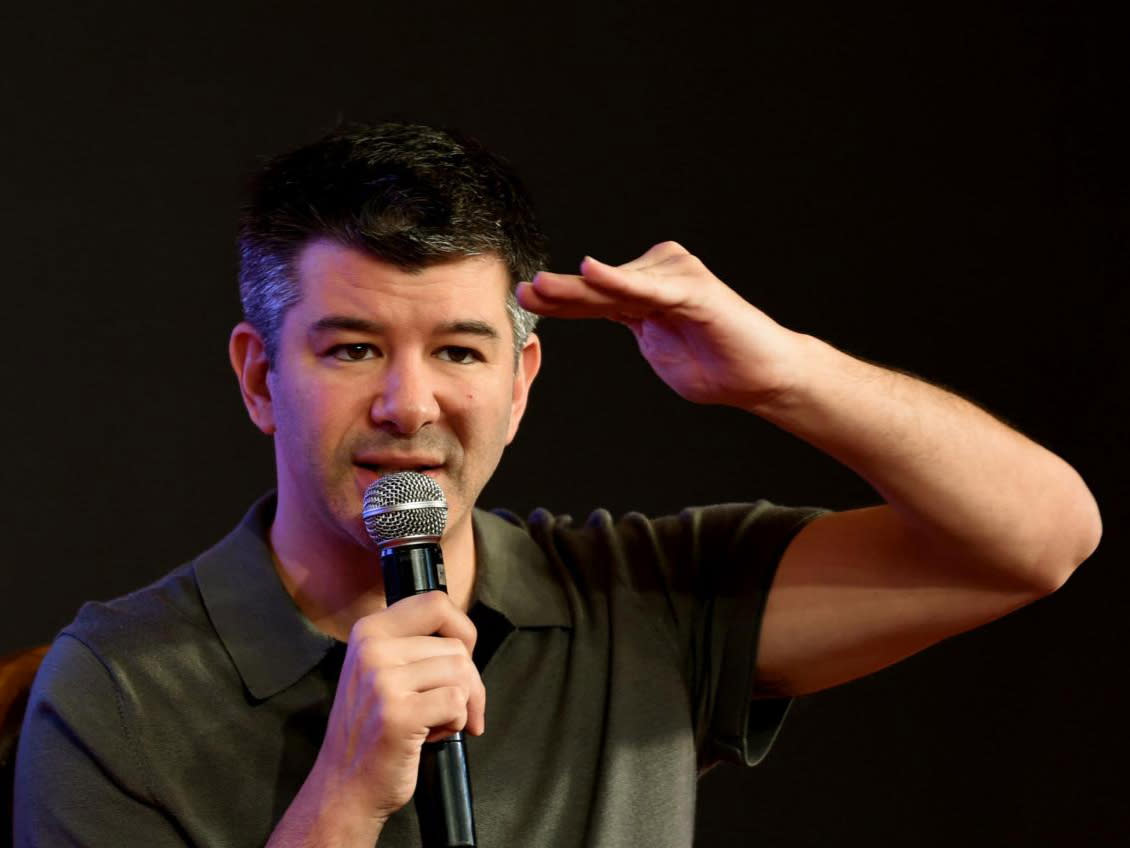

Uber CEO Travis Kalanick's resignation will do nothing to tackle the 'white bro' culture in Silicon Valley

For those following the awkward twists and turns of the Uber story in recent months, CEO Travis Kalanick’s resignation announcement was probably the least surprising morsel of news this year yet.

Kalanick was already on leave from the top role and most Silicon Valley experts appeared to agree that the 40-year-old entrepreneur was destined for the door. Papers had probably pre-written the headlines: “Taxi for Travis”. “Uber and out”.

Look back at the last six months and it’s not difficult to see why.

In January, the #DeleteUber movement swept across social media in response to Kalanick’s ties to President Donald Trump. Hundreds of thousands quit the app under his vigilant, yet defenceless watch. In February, a former engineer, Susan Fowler, posted a tell-all blog that detailed the grim sexual harassment she endured while working at Uber, sparking ferocious global outrage and prompting a major investigation.

Later that month The New York Times published a bombshell piece suggesting the Fowler case was not isolated. Uber employees cited in the article described the work environment as Hobbesian and said that employees were sometimes pitted against one another. A blind eye, the article claimed, was turned to violations from top performers.

Since then investors – who have pumped millions into the app and are terrified what the string of scandals could mean for their returns – have blasted the company for its alleged culture of bullying and harassment. Google has sued Uber for intellectual property theft. A senior vice president at the company was asked to leave after it emerged he failed to tell those who hired him that he had left Google a year earlier in the wake of allegation of sexual harassment.

In a more recent blow, Uber director David Bonderman last week resigned after being accused of having made a sexist remark at a meeting specifically set up to discuss how Uber can transform its culture amid that discrimination probe.

It’s a classic business school case study of a company that’s culturally getting it all wrong and Kalanick, as such, has served as a convenient poster child for the much broader twisted and sickening bro-culture that’s dominating Silicon Valley’s booming startup scene.

Yes, his resignation certainly sends the right signal and proves that Uber does indeed possess some form of moral compass. But will it do much to sustainably eradicate the frat-boy mentality thriving in the world of tech? Unlikely.

Firstly, Uber, under Kalanick, is easy to point to as an example of startup culture gone awry because of its meteoric rise and global dominance. It can be hated on effortlessly.

Everyone knows Uber and it’s easy to level criticism at the company because so many have paved the way already and are standing by, ready to join the chorus of condemnation: local cab drivers who say Uber is destroying their livelihoods, activists bemoaning a lack of worker’s rights in the gig economy, anyone concerned about inadequate background checks on drivers. The list goes on.

I’d never want to downplay the seriousness of any of these concerns and it’s paramount that we keep talking about them, but it’s equally important to remember that Uber has blazed a trail for other budding entrepreneurs and disruptors. So the issues we’re facing extend well beyond Uber.

Scores and scores of hyper-intelligent, ambitious, wannabe entrepreneurs are striving to emulate Kalanick’s success. Yes, he’s left the top spot for now, but they’ve seen that his strategy and style made it possible for him to create a behemoth of a disruptor and earned him a billion-dollar fortune. He’s also still got a spot on the board.

Perhaps the Kalanick’s of tomorrow are today’s Uber fresh-out-of-university hires and anyone who has worked at a big company for a significant amount of time will know how hard it can be to shake corporate culture, practices and attitudes.

Silicon Valley is also somewhat of an echo chamber. Fellow Ivy League alumni sit on the boards of each other’s companies or act as advisors, consultants and mentors to each other. Mentalities, beliefs and opinions are shared. There’s another Kalanick out there who will prove just as feeble when it comes to stamping out a culture of discrimination and inequality.

In 2014, one of the founders of Tinder, another roaring startup success, sued her co-founder accusing him of publicly calling her a whore. She claimed at the time that the chief executive had dismissed her grievances and that her male colleagues had stripped her of her founder title, saying that having a woman on the founding team would “make the company seem like a joke”.

In 2015, Kelly Ellis, a software engineer at Google made headlines when she tweeted about recurring sexual harassment at the company.

Examples are abundant – and those are just the ones that made it into the public realm.

The numbers speak volumes too. At Facebook, Google, Twitter & co, workforces are still very much homogenous and minorities account for a pathetic proportion in the upper echelons of leadership. It’s hard to shut down a sexist or racist joke if you’re the only woman or black person in a board room full of guffawing white men.

Efforts are being made and high-profile women like Arianna Huffington are being roped in to try and alter the course of developments and salvage what’s left to be salvaged.

Getting rid of Kalanick as top dog is a praiseworthy move, but for the wider Silicon Valley his departure may be little more than a tiny step in the right direction. Brace for more of the same.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News