Urban crime plummets during lockdowns in cities around world

Urban crime ranging from vehicle theft and burglary to robbery and assault fell substantially during Covid lockdowns as stay-at-home orders around the world cleared the streets and ensured more houses were occupied in the daytime.

An analysis of crime reports from 27 cities in Europe, Asia and the Americas found overall urban crime fell by more than a third while lockdowns were in place and then steadily climbed back up when restrictions were lifted.

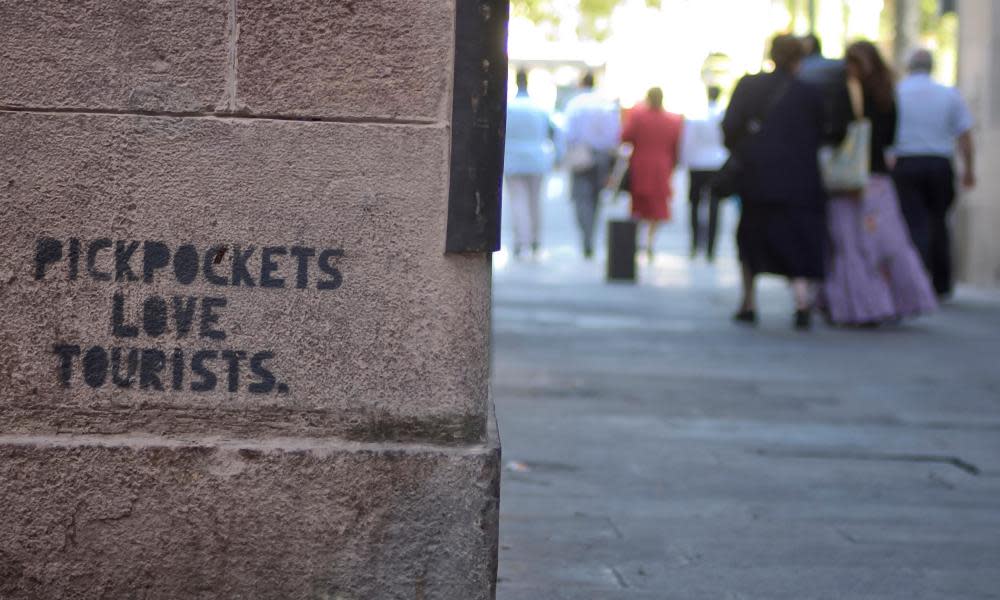

Robberies fell on average by 46%, and vehicle theft and daily assaults were down 39% and 35% respectively. Burglaries dropped by 28% overall, while more minor crimes such as pickpocketing and shoplifting fell by about 47% across the countries studied.

Manuel Eisner, a professor of criminology at the University of Cambridge, said the declines were sharp but short-lived, with the lowest crime rates reported two to five weeks after lockdowns came into force. “After that, the figures start to creep up again,” he said.

In London, robberies fell 60%, thefts by 46% and burglaries 29%. Reports of stolen vehicles were down 26% during the lockdown last spring, and assaults in the capital fell by 10%, the researchers found.

Working with Dr Amy Nivette at the University of Utrecht and others, Eisner found that the strictest lockdowns pushed crime down most, though cities such as Stockholm and Malmö in Sweden, which had only voluntary recommendations, also recorded drops in daily thefts.

The lockdown in Spain, one of the strictest in Europe, transformed urban crime in Barcelona, with assaults falling 84% and robberies down 80%. Police-recorded thefts in the city dropped from an average of 385 a day to 38 under lockdown.

The analysis, published in Nature Human Behaviour, shows how sudden and substantial restrictions on people’s mobility dramatically changed the picture of urban crime, and how swiftly levels rose again when restrictions eased and the normal opportunities for criminal activity returned.

According to the study, lockdowns had far less impact on homicides, which dropped 14% on average. This may be because many homicides take place in the home, but how organised crime gangs responded to the lockdowns matters too, Eisner said.

In a January paper titled Druglords Don’t Stay at Home, researchers in Mexico found conventional crimes fell during the pandemic while organised crime, including homicide, robbery and kidnapping, did not.

In other countries the situation is different. Homicides in Lima in Peru, Cali in Colombia and Rio de Janeiro in Brazil – all cities where a large proportion of murders are down to gang violence – fell 76%, 29% and 24% respectively during lockdown. In some cases, gangs may have helped to enforce lockdowns or, seen another way, imposed their own restrictions on territories they controlled.

Prof Tom Kirchmaier, the director of the policing and crime research group at London School of Economics, who was not involved in the work, said it confirmed the suspicion there was a strong link between the stringency of lockdowns and general crime levels. “If one can’t go out then it is much harder to commit crimes,” he said.

“Having said that, work I did with colleagues found that domestic abuse amongst current partners and family members increased considerably, and that bicycle thefts were quite prevalent during the lockdown as people needed alternative forms of transport.

“The big issue is what will happen after the lockdown ends, and the true costs of the lockdown in terms of economic and social costs in certain areas of the country will become apparent. My gut feeling is that we are in for a bit of a shock – in particular in more deprived areas – with persistently higher property and violent crime levels.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News